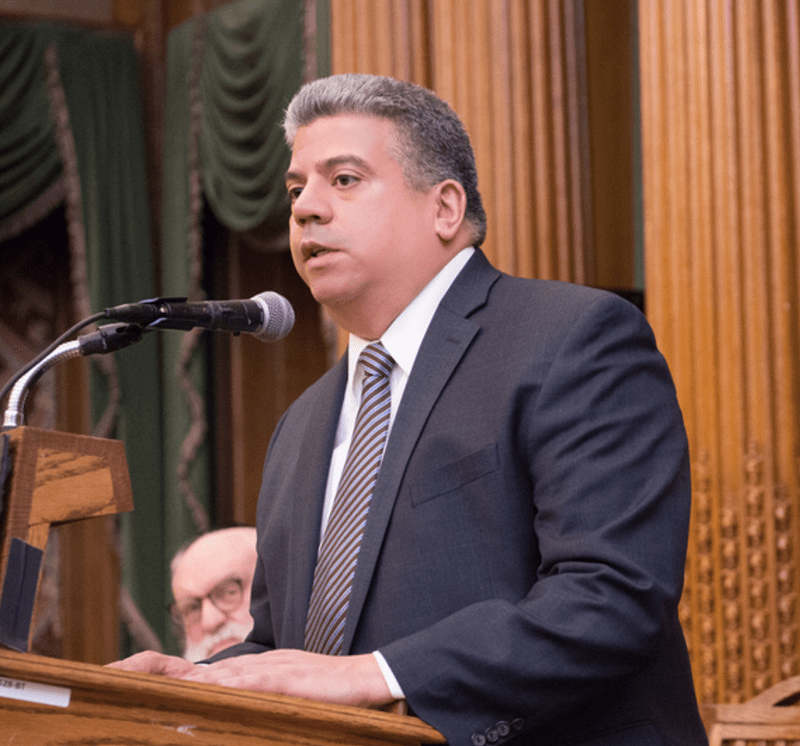

Like Cy Vance, Brooklyn DA Eric Gonzalez Takes Questionable Attorney Donations

“It’s time that candidates for local District Attorney just say no to campaign donations from criminal defense lawyers,” Preet Bharara tweeted on October 12 in response to the scrutiny of the financial support Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance received from lawyers representing Harvey Weinstein as he faced potential charges for his sexual assault of Ambra Battilana Gutierrez. […]

“It’s time that candidates for local District Attorney just say no to campaign donations from criminal defense lawyers,” Preet Bharara tweeted on October 12 in response to the scrutiny of the financial support Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance received from lawyers representing Harvey Weinstein as he faced potential charges for his sexual assault of Ambra Battilana Gutierrez.

That former U.S. attorney Bharara, who made his name as a corruption fighter and is now a social media star, would address donations to district attorneys shows how potent the issue has become.

In his first public comments since the Weinstein scandal broke, Vance also suggested that it may be time to “rethink” his office’s acceptance of such donations. At the same time, he noted that it is “common practice” among DA’s to take money from defense attorneys, a point illustrated by the recent fundraising of Vance’s local counterpart, Acting Brooklyn DA Eric Gonzalez.

New York State Board of Election filings show that with substantial financial support from Brooklyn lawyers, Gonzalez has raised two-million dollars towards his election next month. Along the way, defense attorneys in a number of headline-making cases have made significant donations to Gonzalez.

As stipulated on Gonzalez’s campaign website, “the following restrictions do NOT extend to attorneys representing persons or entities” with the DA’s office: no cases “presently pending,” or any resolved in last 90 days. In other words, defendants in such cases cannot contribute, but their lawyers can.

Yet an examination of Gonzalez’s campaign donations from attorneys with active Brooklyn cases shows the potential conflicts that arise with such routine transactions.

Attorney Joseph Mure represents a central figure in a sordid Park Slope murder case that splashed across the tabloids this past June. His client is a woman who went home with two men for a threesome, then got upset when one of the males started taking cell-phone video. She called her boyfriend in Staten Island, and reportedly claimed to have been raped. Her boyfriend then arrived with his entourage and beat one of the initial male participants in the threesome to death.

In September, Mure added $1,000 to his earlier contribution of $1,500. While that’s a relatively modest sum, Mure is a Trump supporter, whereas Gonzalez made his opposition to Trump a central theme of his campaign. So political affinity doesn’t explain the campaign contributions.

Scott Rynecki is a familiar name beyond the Brooklyn courthouse, given that his law partner is Sanford Rubenstein, who used to work closely with Rev. Al Sharpton on high-profile police misconduct cases. While Rubenstein is in front of the cameras, Rynecki handles the litigation. The duo’s civil suits, however, are often linked to the DA’s criminal prosecutions.

In the Akai Gurley case — in which an unarmed black man was shot in the stairwell of a housing project in East New York — Rynecki parlayed the Brooklyn DA’s office’s successful conviction of NYPD officer Peter Liang into a civil settlement of over $4m for Gurley’s domestic partner in 2016. In mid-August of this year, Rubenstein and Rynecki met with Gonzalez, advocating criminal charges in the police killing of Dwayne Jeune. And on August 21, Rubenstein was at the Brooklyn courthouse again, representing a woman sexually assaulted by an on-duty court officer as she waited for her boyfriend to be released on bail.

On August 28, with the two cases pending before the Brooklyn DA’s office, Rynecki made his third $2500 donation to Gonzalez’s campaign.

Jay Schwitzman, former president of Brooklyn’s Criminal Bar Association, was one of Gonzalez’s earliest donors, chipping in an initial $2500. Throughout the first eight months of 2017, he added another $10k.

In July of this year, Schwitzman’s client Brian Williams went to trial and was convicted for a February 2016 homicide in Canarsie. On August 24, Schwitzman gave Gonzalez $2500. Earlier this month, Williams received a 20-year sentence for 1st-degree manslaughter, four years less than someone sentenced on a top charge of 1st-degree assault that same week, but who was represented by a different attorney (with no direct ties to Gonzalez).

Schwitzman also recently joined a recent high-profile case that involved disturbing allegations of a mid-September 2017 sexual assault by a school aide of an autistic 5-year-old inside a public school in South Brooklyn. In early October, just as Brooklyn prosecutors announced that they were reducing the charges from felony to misdemeanor assault, the Daily News reported that Schwitzman has taken over the case from the public defender.

Schwitzman’s successors as president of the Criminal Bar Association, Michael Farkas and Michael Cibella, were also steady contributors to Gonzalez. Farkas, who helped solicit funds for the campaign, gave just under $5k, while Cibella added $4500. Gonzalez attended Cibella’s swearing-in last January, as did Farkas and Matthew D’Emic, Brooklyn’s chief administrative judge who assigns criminal cases. Fortunate are the defendants able to afford Brooklyn’s in-network counsel.

The Brooklyn DA’s campaign spokesperson declined to respond to numerous queries from In Justice Today regarding whether Gonzalez would return donations from Schwitzman and other defense lawyers with active cases. But regardless of their direct impact on cases, such contributions amount to the price of doing business for defense attorneys in Brooklyn.

As the embattled Cy Vance stated, the easiest way to eliminate even the appearance of conflict is for DA’s simply to reject donations from attorneys with active cases. The loophole can also be closed, although that would require action in Albany, where ethics reforms somehow never see the light of day. But in general, as Susan Lerner of Common Cause has argued, there’s an urgent need to “remove private money from the criminal justice system and replace it with public financing of elections.”

New York City’s public-financing system offers a workable model. (Because the DA’s are state officeholders, the campaign rules are different.) Among other features, the city’s system caps the amounts that donors can give — $4950 to the mayor, for example — and provides 6–1 matching funds for up to $175 given by city residents. And it prevents anyone with a direct business relationship with the city from contributing more than a nominal amount.

Yet even if the current system remains in place, and DA’s like Vance and Gonzalez continue to accept donations from defense attorneys, this much has changed: Many more eyes are following the money now, putting DA’s on notice that voters may make them pay the price for even a hint of checkbook justice.