‘Like a Bad Dream’: In New Orleans, Witnesses Are Going to Jail Instead of Perpetrators

In the spring of 1983, Donald Mairena witnessed a shooting at New Orleans’ Latin American Club. He chased after the shooter and later told law enforcement what he’d seen. Mairena gave them his address in case they needed any more information from him. He heard nothing about the case until almost two years later, when […]

In the spring of 1983, Donald Mairena witnessed a shooting at New Orleans’ Latin American Club. He chased after the shooter and later told law enforcement what he’d seen. Mairena gave them his address in case they needed any more information from him. He heard nothing about the case until almost two years later, when he was arrested and jailed for nearly a month simply because prosecutors at the Orleans Parish district attorney’s office, then led by Harry Connick Sr., felt that he “might be needed as a witness if the case went to trial.”

Upon hearing Mairena’s case seeking damages from the Orleans DA for violations of his civil rights, judges on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals panel marveled, “The facts in this case are like a bad dream.”

Yet Mairena was far from the last witness to spend time in the New Orleans jail. More than 30 years later, the Orleans DA still regularly detains witnesses by using material witness warrants. Orleans Parish prosecutors obtain the warrants to force a person to testify in court if they believe that person has knowledge of a crime. They are meant to be used in extraordinary circumstances, such as for when a prosecutor suspects that a critical witness in a case might flee.

The Orleans DA’s office has frequently insisted that it is fighting for crime victims when it pursues lengthy prison sentences and fights exonerations. Its mission statement explicitly says the office seeks to “advocate for the victims of crime.”

But since 2010, Orleans District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro has sought more than 150 such warrants to arrest witnesses, including a significant number of victims, according to a data analysis by the Yale Law School students of the legal scholar James Forman Jr. that was shared with In Justice Today.

A 19-year-old victim of sex trafficking was arrested in November 2014, shortly after giving birth to her daughter. She had failed to appear at a hearing during her pregnancy because she was supposed to be on bed rest and had a doctor’s note to prove it. Even so, she was held in jail for nearly four months until she testified against the father of her child.

Another victim who was shot with a semiautomatic rifle was jailed as a material witness on a $100,000 bond in December 2016. Two victims of assault were arrested and jailed on $250,000 bond after they tried to recant their testimony against their alleged attacker.

Cannizzaro’s office generated national outrage — and a lawsuit — in the fall of 2017 over its practice of creating subpoenalike notices to compel witnesses to meet with prosecutors. These fake subpoenas hold no inherent legal power. But the forged documents were given teeth by the DA’s indiscriminate use of material witness warrants.

These witnesses have no right to counsel because they are not accused of a crime. Some have sat in jail for days or months before trial. They are often held on exceptionally high bond, sometimes even higher than the person they are testifying against.

In theory, material witness warrants are meant to be used in rare cases when prosecutors have a reason to fear a witness won’t show up to testify at trial. But Cannizzaro and prosecutors in other jurisdictions have allegedly used these warrants to intimidate witnesses into private interrogations often without attorneys present and to pressure them to mold their version of events to the state’s theory of the crime. In short: Cooperate with the state or go to jail.

The lawsuit filed by the ACLU and Civil Rights Corps, a nonprofit organization that challenges systemic injustice in the American legal system, alleged that the Orleans DA not only issued fraudulent subpoenas, but also secured material witness warrants under false pretenses to arrest witnesses who refused to cooperate with prosecutors.

In a May 9 hearing on the fake subpoena lawsuit, a federal district judge strongly criticized the Orleans DA’s material witness warrant policy.

“What was particularly troubling to me with the material witness warrants is that people, as I appreciate it, were incarcerated for a period of time with no appearance before a judge,” said Judge Jane Triche Milazzo of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana. “It appears to me that people picked up on material witness warrants are being treated differently than people picked up on arrest warrants for crimes. They appear to have fewer rights.”

Indeed, the Yale Law students’ analysis of 159 material witness warrant applications filed by the Orleans DA from 2010 to 2017 offers a window into how this practice often ends up harming the victims and witnesses the Orleans DA office claims it seeks to protect.

They identified at least 25 cases in which witnesses were held on a higher bond amount than the person charged with a crime. In one case, a domestic violence victim was held on a bond of $100,000–20 times higher than that of her alleged abuser, who was given a bond of $5,000. In eight cases, prosecutors sought $500,000 bonds. The records indicate judges almost never denied prosecutors’ requests for high bond amounts.

These high bond amounts meant that when people were detained on material witness warrants, they were likely to stay in jail. Some witnesses with other minor charges against them ended up staying in jail for far longer; at least seven witnesses spent over 100 days in jail. One man was detained for 43 days, about 10 percent of the time the defendant in the case received.

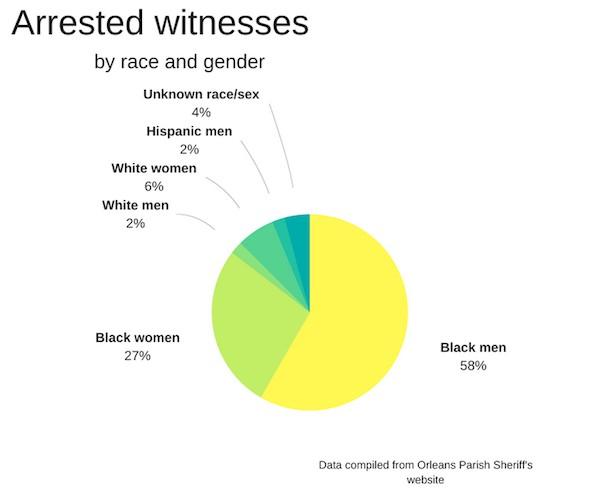

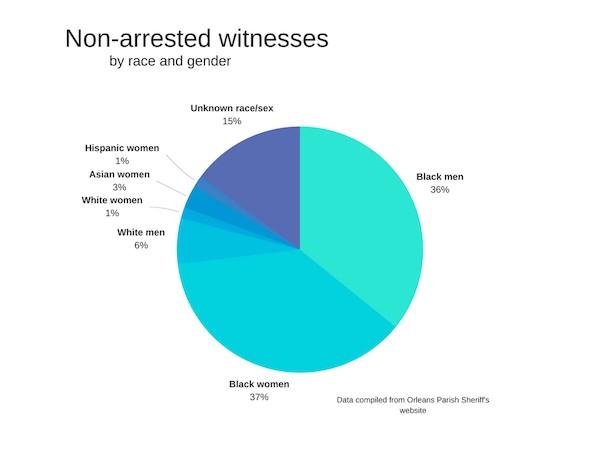

The data analysis by Forman’s law students also suggests that the Orleans DA primarily deploys material witness warrants against black New Orleanians. African Americans made up 78 percent of both arrested and non-arrested material witnesses. Out of 50 people actually arrested on material witness warrants, one was a white man.

In many cases, the Orleans DA requested the warrant based on nothing more than the fact that the witness had refused to meet with prosecutors privately. One warrant was issued for the victim of an attempted murder simply because the office felt he was avoiding meeting with an investigator and victim witness coordinator. According to the motion for a material witness warrant filed by Assistant District Attorney Christopher Cortez, the victim’s father told an investigator with the Orleans DA’s office they did not want to participate in the prosecution.

Another man was held on $100,000 bond to testify against a person accused of unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. The defendant was given a $10,000 bond, while the witness sat in jail for a week. The sole reason given for the warrant was that he had not shown up to private meetings with the prosecutor on the case.

The Orleans DA has continued to request warrants for witnesses even after being sued by the ACLU and the Civil Rights Corps last year. And on May 18, the ACLU issued a statement attacking “Cannizzaro’s “callous treatment of victims” and the “community members who have suffered through years of aggressive, coercive, and retaliatory treatment at the hands of the Orleans Parish District Attorney’s Office.”

Orleans DA spokesperson Ken Daley emphasized to In Justice Today that the judges are ultimately the ones granting these warrants and that the DA has “no power” to jail witnesses without a judge. “Any decision to seek a material witness warrant approval from a judge is made with great care, requiring extensive discussion of possible alternatives and ultimately requiring the personal approval of the DA or First Assistant,” Daley wrote in an email.

But the tide is beginning to turn against the practice.

Prosecutors in other parts of the country have pledged to stop jailing victims of domestic violence or sex crimes. Reform-minded district attorneys, like Distict Attorney Kim Ogg of Harris County, Texas, and candidate Joe Gonzales of Bexar County, Texas, have spoken out against the practice and have sworn never to detain a victim.

The criminal justice accountability group Court Watch NOLA has called onthe Orleans DA’s office to stop incarcerating victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, and at a minimum create a clear policy for when issuing warrants for other victims is necessary.

Louisiana lawmakers could also get involved if the Orleans DA continues detaining witnesses. Other jurisdictions around the country already have safeguards to protect witnesses from indefinite detention. Some states cap the amount of time witnesses may spend in jail, and others give them a right to counsel and a hearing to contest the warrant. New Jersey even requires that witnesses be held in “comfortable quarters and served ordinary food” rather than thrown in jail.

Still, Cannizzaro has resisted all calls for reform. Instead, he has blamed“partisan special interest groups, who strongly oppose my office’s aggressive pursuit of violent criminals” for challenging him on the issue. And his spokesperson Ken Daley argued after the May 9 federal court hearing on fraudulent subpoenas that ending the DA’s policy on material witness warrants would “dislodge the underpinning of our justice system, escalate incidence of witness intimidation, and further endanger our crime-weary community.”

“Asking a judge to detain a victim in any case is a tool of last resort, and is done only when the totality of circumstances show that to proceed otherwise would result in a dangerous defendant walking free to pose a continued threat to the safety of the community we are sworn to serve and protect,” Cannizzaro said in a statement emailed to In Justice Today. “Such occurrences are extremely rare in the nearly 7,000 cases we handle per year between Criminal District and Municipal court. But even as this issue has been grossly overstated, it would be unwise and potentially dangerous to issue any blanket policy that would prevent our ability to assess any criminal case on something other than its own individual merits.”

Several prominent victims’ rights groups disagree. Three victims’ advocacy organizations aligned with the ACLU and Civil Rights Corps against Cannizzaro in a brief filed in federal court in May, detailing how prosecutors are re-traumatizing and manipulating survivors of sexual assault and domestic violence through the use of material witness warrants.

The brief, filed by the Louisiana Foundation Against Sexual Assault, The Domestic Violence Legal Empowerment and Appeals Project, and the National Alliance to End Sexual Violence, emphasizes that jailing witnesses and coercing testimony harms victims. They also argue that these tactics backfire by making witnesses even less likely to cooperate with law enforcement. “It is no stretch to conclude that the abusive subpoena and material witness procedures and retaliatory punishment…will chill the voluntary witness cooperation on which the successful prosecution of sexual assault and domestic violence cases so heavily depends,” they write.

And the groups take aim at the idea that the criminal justice system serves victims, particularly victims of domestic violence, at all. “The goals of victims often are not aligned with those of the criminal justice system,” their brief states.

A 2015 ACLU survey of advocates, lawyers, and service providers cited in the brief found that victims of domestic violence and sexual assault were especially wary of getting mired in the criminal justice system for three main reasons: They wanted “options other than punishment for the abuser, options that were not necessarily focused on separation from the abuser”; they feared “they would lose control of the process” if they continued within the constraints of the criminal justice system; and “they believed that it was complicated, lengthy, and would cause them to suffer more trauma.”

“In essence, power is shifted from the abuser to the state,” one survey respondent explained.

Far from working for them, the criminal justice system can cause even further damage to victims, the report stated. “The criminal justice system is not trauma informed and can re-traumatize a survivor of violence,” another respondent said. “Many survivors I have worked with that did go through the criminal justice system wish they had not after the fact because it negatively impacted their ability to heal from trauma.”

Further punishing traumatized victims simply confirms their worst fears about participating in the system. As the victims rights’ groups wrote in their brief in federal court, “The coercion and retaliatory punishment plaintiffs allege compounds that destabilization, thereby turning on its head the role the criminal justice system should play for crime victims and witnesses.”

Susanna Evarts, Adeel Mohammadi, and Hannah Schoen contributed research to this story.