Law Enforcement Is Urged to ‘Think Like a Parent, Not a Prosecutor’

A new DA in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, is treating the overdose crisis as a criminal matter rather than a community health issue.

Sophia Signor was looking to buy drugs, but she was short on cash. So she reached out to a friend.

“I can’t even come up w ten more dollars this is pathetic I’m about to stop trying,” she wrote to Jacob Rettig in a text message that day, Nov. 12, 2018. “But I’m dying.”

Signor got $20 from Rettig and contacted another friend who drove her about 15 minutes to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where Signor purchased what she thought was heroin.

Signor was then driven back across the Susquehanna River to Rettig’s house in East Pennsboro Township, in Cumberland County. During the drive, Signor told Rettig that the drugs looked different than she was used to.

“It’s diff idk what it is yet,” she wrote in a text.

“Is it real?” Rettig asked. “I swear to God with this make up shit.”

This time the drugs were real, but they weren’t heroin.

Around 4 p.m. the next day, Rettig was found dead in his home. An autopsy determined that he died of an overdose of fentanyl and mitragynine, the main chemical found in kratom, a largely unregulated herbal supplement. During an interrogation on Nov. 16, Signor told police she had purchased suboxone and heroin for Rettig but it turned out to be fake. Police identified Signor and the man who gave her a ride to Harrisburg through Rettig’s phone records.

On May 23, East Pennsboro Township Police Sgt. Matthew Roberts charged Signor, 22, with felony drug delivery resulting in death and felony criminal use of a telephone. She was arrested a few days later. Despite qualifying for a public defender, Magisterial District Judge Anthony Adams set her bail at $100,000, which she was unable to pay. She was taken to Cumberland County Prison.

Under the state’s criminal statutes, a person can be sentenced to up to 40 years in prison for intentionally providing drugs to someone who then uses, or otherwise ingests, the drugs. There is no requirement for the state to prove that the person intended to kill the victim. The charge has become popular with prosecutors in response to the overdose crisis, which has been driven in large part to a rise in deaths from prescription opioids, heroin, and fentanyl (what many people call the “opioid epidemic”). In 2017, the latest year for which complete data is available, more than 5,400 people died by overdose in Pennsylvania.

In Pennsylvania, the number of people charged with drug delivery resulting in death increased more than tenfold between 2013 and 2017, with a large surge in 2017. A national study by Health in Justice Action Lab at Northeastern University School of Law found less than half of drug-induced homicide cases between 2000 and 2017 involved a traditional dealer-buyer relationship. “These types of laws were designed to target kingpins and drug dealers, but that’s not how they’re being used,” Devin Reaves, executive director and co-founder of the Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Coalition, told The Appeal. “We’re seeing an abundance of charges being filed against friends and family members.”

David Freed, who was the district attorney of Cumberland County until November 2017, didn’t view the charge as a way to combat the rise in overdose deaths. He acknowledged that charging people with criminal homicides for overdose deaths does little to deter drug use and sharing drugs among friends. President Trump appointed Freed as U.S. attorney for the Middle District of Pennsylvania in 2017, and Judge Skip Ebert was appointed to replace him as DA. Ebert has taken a different approach.

Since taking office in January 2018, Ebert has filed more drug delivery resulting in death cases than Freed did in more than 10 years. In the first year of his appointment, Ebert filed 13 cases. He has filed another nine so far this year. Many of these cases have been filed against people who either share drugs or who also use drugs. He has even made seeking more of these charges a plank in his bid for election this year. Ebert won the Republican primary in May and is likely to win the general election, in November, against the Democratic challenger Sean Patrick Quinlan. There are nearly 30,000 more registered Republicans than Democrats in Cumberland County.

In 2017, Ebert filed a conspiracy to commit drug delivery resulting in death charge against a woman who helped a man buy groceries, which he then traded for drugs. The conspiracy charge carries the same maximum possible sentence as if she had sold him the drugs herself.

Ebert has touted criminal enforcement as a way to prevent overdose deaths, but he told The Appeal that drug delivery resulting in death prosecutions tend to be more about punishment.

“It’s probably more punishment, because the consequences are so high that someone dies and [dealers are] making money off of it,” Ebert said. “The people that are in this business who are going to say ‘I’m not going to do this anymore because it has a heavy penalty,’ I don’t think they’re thinking about [the penalty].”

Ebert said he does consider whether the person is sharing drugs, as opposed to selling, when filing criminal charges, but he also said the rise in overdose deaths has put pressure on law enforcement to treat overdoses as a criminal matter. A 2011 change to the drug delivery resulting in death statute removed the need for prosecutors to prove the person delivering the drugs intended to kill the victim. That change, coupled with easy access to phone records and text messages, has also made prosecuting these cases easier, Ebert said.

“Before the overdose crisis, there were a lot of times the coroners just wouldn’t call us,” Ebert said. “It wasn’t considered a law enforcement thing.”

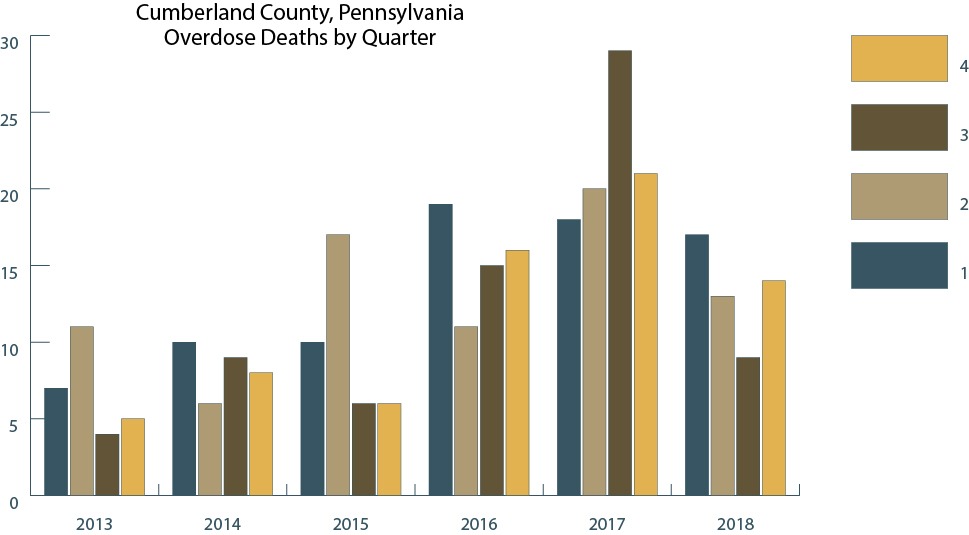

In 2018, overdose deaths did drop by about 40 percent in Cumberland County compared to a year earlier. However, according to a review of county death records, overdose deaths peaked in the third quarter of 2017. Such deaths began declining in the fourth quarter of that year, before Ebert took office, and have continued declining.

Reaves of the Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Coalition said the heavy reliance on such a punitive charge, especially when filed against people who share drugs, could result in people being unwilling to call for help during an overdose. The state legislature passed a good Samaritan law in 2014 that provides immunity from certain criminal charges for people who call for assistance during an overdose and for overdose victims. The law doesn’t protect people from being charged with drug delivery resulting in death.

“We passed [the good Samaritan law] as a harm-reduction measure because we knew people weren’t calling 911,” Reaves said. “Now, we’re taking a huge step backward.”

In April, a woman was found dead in her driveway and an investigation determined that she died of an overdose after she shared drugs with two other women. The other women panicked when the victim began overdosing and instead of calling for help, left her to die. Both women are now charged with drug delivery resulting in death and are being held in Cumberland County Prison, like Signor, awaiting trial.

“My guidance to any key decision maker in bringing these charges is: Please think like a parent, not a prosecutor,” Reaves said. “One life and one family has already been destroyed by the loss of a loved one. Do we want to destroy another one, or do we want to invest in that person and help them find recovery?”