Justice in America Episode 19: What Justice Could Look Like

Josie and Clint talk to Sonya Shah, an associate professor at the California Institute of Integral Studies, about restorative justice.

On this episode, we talk about an alternative to the traditional criminal adversarial process: restorative justice. Restorative justice focuses on repairing the harm caused by wrongdoing, and values reconciliation, community-involvement, and accountability over punishment and retribution. We discuss the benefits, limitations, and potential of restorative justice. We also talk to Sonya Shah, an associate professor at the California Institute of Integral Studies and a renowned restorative justice facilitator, trainer, and expert. Sonya is a survivor of child sexual abuse, and has worked extensively with survivors of sexual abuse and people who have committed sexual harm. In 2016 she founded The Ahimsa Collective, which offers non-punitive approaches to addressing and healing harm through the lenses of restorative and transformative justice. This episode also features audio from Danielle Sered, Executive Director of Common Justice.

Additional Resources:

More on Sonya and The Ahimsa Collective can be found here.

Here’s The Appeal piece we mentioned about the Oakland Restorative Justice program that is currently facing the chopping block.

For more on some of the restorative justice programs Sonya mentioned, check out Restorative Response Baltimore and Nashville’s New Restorative Justice Program Allows Youth Offenders.

And here’s more on Howard Zehr, considered the “grandfather of restorative justice” whom Sonya also mentioned.

Danielle’s new book, Until We Reckon, can be found here. The book was also mentioned in a recent New York Times piece by Michelle Alexander, called Reckoning with Violence.

Also check out Impact Justice, a phenomenal organization that does really critical restorative justice work, and Sujatha Baliga is a leader in this field. Here’s a video of Sujatha and Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner talking about their work.

Also check out this piece in Vox about restorative justice, written by Sujatha.

Restorativejustice.org has a ton of great resources on restorative justice, including a tutorial and a library full of further reading.

Here’s more information about Pod Mapping, which we highly recommend reading about! It’s a powerful and effective way to conceptualize your interpersonal relationships and your community.

Justice in America is available on iTunes, Soundcloud, Sticher, GooglePlay Music, Spotify, and LibSyn RSS. You can also check us out on Facebook and Twitter.

Our email is justiceinamerica@theappeal.org

Transcript

[Music]

[Begin Clip]

Sonya Shah: Restorative justice is really about being a community based solution to dealing with harm and violence when it occurs. And that’s completely the opposite of our criminal justice system, a retributive system which is basically a lock them up and throw away the key approach where no one really cares about what happened to the victim, they’re just used for conviction, and no one really cares what happened to the person that did the harm.

[End Clip]

Josie: Hi, I’m Josie Duffy Rice.

Clint: And I’m Clint Smith.

Josie: And this is Justice in America. Each show we discuss a topic in the American criminal justice system and try to explain what it is and how it works.

Clint: Thank you so much everyone for joining us us today. You can find us on Twitter @justice_podcast, like our Facebook page at Justice in America and subscribe and rate us on iTunes. We’d love to hear from you and it really helps.

Josie: We opened with a clip from our guest, Sonya Shah, an Associate Professor at the California Institute of Integral Studies. Sonya currently works at the intersection of restorative justice and issues like trauma healing, sexual violence and structural oppression. She will be talking to us about our topic for today, which is a little different than what we normally talk about.

Clint: So, usually we talk about problems on this show because understandably there are a lot of them. We talk about what is wrong with the system. And we usually spend pretty much no time on solutions honestly.

Josie: Right. And the reason for that is pretty straight forward. This system is very complicated. There isn’t just one reason that things are this way. You know, you’ll hear people say mass incarceration came from the drug war or mass incarceration is because of stop-and-frisk but the reality is there are a million reason why the system looks the way that it does. One because there isn’t just one problem, there likely isn’t just one solution. We’re not going to pass one law and fix the whole system. We’re going to briefly talk about two very interesting and important ideas that demand a radical rethinking of our whole system.

Clint: But before we get into restorative justice it’s time for our word of the week. And it’s our bad that we have not thought of a better term for word of the week and our bad that our word of the week is often more than one word but we’re trying to do our best.

Josie: We swear that we are actually creative people who should have thought of some good puns. I thought of “crime-time.” (Laughs.)

Clint: Oh man. Okay, so, we’ll keep Josie off the stand upstage but as you may know, every week we spend just a quick minute talking about a word, a phrase or a term related to our criminal justice system that is misused or misunderstood or frankly just useless.

Josie: Yeah and so this week the phrase slash term slash thing we’re talking about is the crime rate. [Bell]

Clint: The crime rate. Politicians and pundits and commentators love to talk about about the crime rate and sometimes like to misrepresent it. It’s a very popular term. And the concept as I said is massively misunderstood, and as a result is basically used to manipulate the public. Politicians use it to score points, local news uses it to make sure you tune in every day for the latest details on the latest crime.

Josie: But what exactly is the crime rate and what does it tell us? More importantly, what does it not tell us and what are its flaws?

Clint: Basically, the crime rate is a per capita number, representing the number of crimes per 100,000 residents. The Department of Justice releases two sets of data every year — the Uniform Crime Reports, which is released by the FBI and the Bureau of Justice Statistics,’ which I can never pronounce correctly-

Josie: I know it’s so hard.

Clint: And the BJS’ National Crime Victimization Survey. The Uniform Crime Reports, or UCR, is compiled from data from 18,000 different law enforcement agencies. The NCVS is compiled from a survey of about 90,000 households, which asks people 12 and older whether or not they were crime victims. Generally, the UCR’s rate is the most commonly used one.

Josie: But there are other crime rates too that you might hear right? So maybe your local government or your local police department has calculated their own crime rate. Or maybe your state government has done it. And you may wonder why they would need to do that if the FBI is already doing it for them. But the reason is because the FBI’s numbers end up kind of being very general. So 18,000 police departments send data on 28 different crimes to the FBI every year. But of course, each state categorizes crimes differently. So what may be a Category 1 misdemeanor in Massachusetts may be a Level 3 felony in Florida. So the FBI splits everything into just two general categories called Part 1 and Part 2.

Clint: Part 1 includes the most serious stuff — murder, rape, robbery, robbery, larceny, car theft, arson. Part 2 is pretty much everything else — simple assault, public drunkenness, drug possession, embezzlement, DUIs, loitering. Although as an aside, my personal view, there should be questions why things like embezzlement shouldn’t be considered the more serious stuff.

Josie: And why loitering is on there at all but-

Clint: Exactly.

Josie: Yeah. We digress.

Clint: We digress. They separate all crimes just into these two categories. Part 1 is then split into two smaller categories — violent crime and property crime.

Josie: So basically we have serious violent crimes, serious property crimes and everything else. And in general this Part 1 — the serious crimes — these are what the FBI gives the most attention. But lumping all these charges together like this makes it hard to tell what crime is really like just by looking at the crime rate. The violent crime rate, for example, as defined by the FBI, includes about half the crimes the FBI categorizes as serious. So that rate includes a woman being murdered, and it also includes a man stealing a pair of sneakers from the store. Those two things are so vastly different, and combining them is at the very least unhelpful and actually it ends up being pretty misleading. But that’s what you’re getting with the typical crime rate.

Clint: Second, the crime rate doesn’t account for geographical specificity. As we’ve mentioned before, overall, crime in America is near record lows, but you would never know it from watching the local news.

Josie: Exactly.

Clint: For a few decades now crime rates across the country have been steadily decreasing, and now America is overall safer than it’s been since the 1970s. But that doesn’t actually tell you or me or anyone what daily life is actually like. Because crime is down in, say, LA, doesn’t mean it is down in St. Louis. And this is why it is important to disaggregate data. Because it is down in one neighborhood doesn’t necessarily tell us anything about what might be very different a few miles away.

Josie: For many people, especially those living in certain suburbs, crime is virtually non-existent. And we say that honestly. The chances of someone robbing your house is close to zero. You know, there are places in America where you could leave your kid outside with a sign that says “please kidnap me” and nobody would touch your kid. But someone would probably call child protective services on you.

Clint: Probably.

Josie: But still, in some neighborhoods there is just no crime at all.

Clint: And for other people, in particular in neighborhoods in cities like Baltimore or Newark or Cincinnati, where the residents are more likely to be poor and minority, crime is actually as high or higher than it’s ever been. There are countless factors that contribute to this, from the lack of resources given to local schools to rising inequality to a housing crisis that has manifested itself for the past several decades that creates hyper segregation in communities where crime and poverty can often be concentrated.

Josie: Right. The concentration, it matters a lot. And that’s why the national crime rate tells us so little. Even state crime rates tell us very little. So what’s happening in Prince George’s County is not what’s happening in Baltimore County which is not what’s happening in Baltimore City. For example, in 2016, St. Louis County’s homicide rate was about 3 per 100,000 people. The city of St. Louis’s homicide rate was around 60 per 100,000 people. So the city’s homicide rate was twenty times that of the immediate surrounding county.

Clint: So here’s another reason why crime rates are basically trash. So like we said earlier, the Uniform Crime Report is measured by data provided by local police departments. Most departments, apparently around 90 percent of departments, return that information. Which given the fact that the federal government can’t exactly compel them to complete these surveys, is pretty good. But oftentimes what they are reporting is really really inaccurate.

Josie: That other big data set we mentioned, the National Crime Victim Survey, has found that less than half of crimes are reported to the police. When they’ve surveyed victims every year, almost 100,000, and they’ve asked them questions about crimes that have been committed against them, only about 42 percent of people surveyed say that they reported their crime to the police. In certain places, like New Orleans, police are so slow to respond to calls— I think 73 minutes is the average wait before police show up if you call them in New Orleans— and so calling the police is kind of pointless anyway. But we’re also talking about communities where distrust of law enforcement is deep rooted and with good reason. So when you read the crime rate, you’re not actually getting the full story.

Clint: And one last thing. Percentages can be, let’s say — misleading. At the Republican National Convention in July 2016, Donald Trump stated, “Homicides last year increased by 17 percent in America’s fifty largest cities.” He said that the 17 percent increase in the homicide rate was quote, “the largest increase in 25 years.”

Josie: You have to imagine Clint saying that in Donald Trump’s voice. That’s a very important part of this.

Clint: (Chuckles.) But that actually depends on how we define increase, and what an increase is. In other words, if we take that 17 percent number to be accurate, it may be the largest percentage increase, but not necessary the largest numerical increase.

Josie: Right, so, because crime rates are already so so low, a really small increase can result in a big percentage change. Let’s say, for example, that a city has eight homicides one year and twelve the next. That four-person increase equals a 50 percent increase in the murder rate.

Clint: Or if a city has one murder and then the next year two people are murdered, the murder rate increased by 100 percent.

Josie: Right. Exactly.

Clint: So just so people can follow and understand, cause I know we have a whole lot of numbers we’re throwing at you, the homicide rate in 2014 was 4.5 homicides per every 100,000 people. And in 2015, it was 4.9 homicides per 100,000 people. So actually only a .4 increase in the number of homicides per 100,000 people, but that’s equivalent to the 17 percent increase that Trump is alluding to. So you can see how the numbers can sort of distort the reality or the raw numbers that we see on the ground because the numbers are so small to begin with.

Josie: Right.

Clint: And so, for example, in 1991, the rate was 9.8 homicides per 100,000 people which was literally twice as high. So, even if we take Trump at his word and the 17 percent statistic at face value, that jump in percentage doesn’t mean that we’re seeing homicides rise nearly as much as they did 25 years ago.

Josie: That’s right. Yes. So these are the reasons you should think twice everytime that you see the crime rate mentioned. [Bell] we’re going to go back to today’s topic. Restorative justice is a term you may have heard of. I think it’s certainly been getting more and more attention over the past few years. And basically, it’s a way of addressing harm that focuses less on punishment and more on healing. And not just healing the person harmed or the person responsible but a more collective healing that includes the community.

Clint: Exactly.

Josie: Here is Danielle Sered, the Executive Director of Common Justice and author of a new book called Until We Reckon, talking to us about the value of restorative justice.

[Begin Clip]

Danielle Sered: Restorative justice is a process in which the people directly impacted by particular harm come together to reach a decision about what to do to make things as right as possible. And so that has a few key elements. It means that the decision makers are the people whose lives are at stake in the outcome: those who’ve caused harm, those who were harmed, the loved ones of both. It means its a decision making process. So it’s not just a process that is about dialogue or conversation but about outlining a course of action that will address the harm that occured. And it’s aim is about repair. That distinguishes it from the criminal justice system in core ways. The key actors in the criminal justice system are not in fact the people most directly impacted. You’ll see in courtrooms that its the prosecutor versus the defendant and the victim is nowhere to be found even though that person sustained the harm for what is being addressed. The decision making process that happens in court is constrained by the law and unrelated to the particular impact that that harm had on someone’s life. And the aim of the criminal justice system is not repair. It’s job is punishment, in some ways its job is containment but it’s job isn’t repair. I’ve said at times it’s as though what the criminal justice system can do is if someone burned down your house it can burn down their house but it can’t rebuild yours. The aim of restorative justice is to do some of that labor of rebuilding and to put the responsibility of some of that rebuilding on precisely the person who caused the harm. At its core, restorative justice believes that the harm to people matters fundamentally, that it is about harm within relationship not just broken rules and that that harm within relationship requires repair.

[End Clip]

Josie: So what does restorative justice actually look like?

Clint: It’s not a trial, but more of a mediation. And it involved the person harmed, the person who committed the harm, and any other community member that may be needed. For example, the process could include other survivors, perhaps or parents of those involved or friends. Also, — and importantly — the restorative justice process requires a facilitator, a person trained to ensure all parties are able to find a way of reaching restitution.

Josie: The process begins with the facilitator asking the person who has been harmed what they want out of this process. And people who work in restorative justice say that what many harmed parties want is just for the person who harmed them to admit their wrongdoing. They want the person responsible to admit that they are telling the truth. To take responsibility. And maybe they also want a clear apology or maybe they want a different type of result. Maybe they want something that requires more time and sustained engagement. Maybe they want that person to admit to their friends and family the harm they caused. Whatever it is, the survivor is naming reparations and identifying possible ways the responsible party can make amends. To be clear these are not punishments. But they are things that may be hard for the responsible party to do. Whatever it is, the restorative justice process focuses on getting all parties to the right solution.

Clint: The restorative justice process is not necessarily just one conversation. It can take many meetings over many days or weeks or months, depending on the harm and the set of circumstances. This gives those harmed the opportunity to talk face to face with the person responsible, and allows them to articulate exactly what the harm has done to them. The entire process centers on the person who is harmed— the survivor— and it concerns itself with both the survivor and the responsible party. Ultimately, the process needs buy-in from both in order to find a real solution and in order for healing to be possible. But, if both parties do choose to engage in the process, both parties can also benefit from it. Here’s Danielle Sered again, talking about the benefits of restorative justice for not only the harmed party, but the person who caused the harm as well.

[Begin Clip]

Danielle Sered: So I think in our culture we have an understanding of healing processes to some degree. We understand that when something happens to us or when we lose someone there are stages that we will have to go through or steps we will have to take to help restore us to a sense of connection, to a sense of dignity, to a sense of self love, to a sense of hope. And I think that because I actually continue to believe, despite all the things we see in the world, that people are fundamentally good. I believe that when we cause harm it damages us in some way and we know it’s wrong and it feels that way. And the best way, the best word I know for that feeling is shame. And I’ve looked for a long time for pathways out of shame other than accountability and I’ve never found a single one. I really have come to believe that the only pathway out of shame is to be accountable. And that just like grief, for those of us who are hurt, restores us to those feelings of self love and connection and dignity and hope. For responsible parties it is the process of making right that helps restore them to feelings of dignity and self love and connection and hope. That I think accountability is the corollary to grief for those of us who have caused harm and I think until we have made things as right as we can we’ll carry that shame in a way that harms us and in a way that increases the likelihood that we will harm others. And so at Common Justice we think of accountability as an act of love. We think of accountability as a pathway to dignity. And we think of accountability as something that often allows those who have been responsible not only to make right with what they’ve done but also to heal through the things that have been done to them. Not in a way that excuses their behavior but in a way that helps them develop insight into it and to transform it.

[End Clip]

Josie: Restorative justice isn’t available to everybody in every situation. And in fact, its footprint is still relatively small. But it has still grown enormously over the past decade or two. It’s being used in schools, involving juveniles accused of wrongdoing, anything from stealing from one student to sexual assault. It’s been used in prisons — last year, I spent a weekend at a restorative justice retreat in a Massachusetts prisons. Some jurisdictions have restorative justice diversion programs, where the court encourages the people to find healing outside of the courtroom. It’s even been used on a much larger nationwide scale, like in South Africa with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Clint: There are criticisms of restorative justice. To be clear, it’s not perfect. First, the fact that both parties must agree to even take part in the restorative process means it is limited in the situations in which the responsible party is interested in amends in the first place. That can obviously be limiting into who is participating or not participating in the process. There are also of course situations in which the person who has caused harm is coerced into the process by the looming threat of criminal consequences, but even then they have a stake in the resolution.

Josie: People also criticize restorative justice for keeping professionals out of the process. Not just legal professionals but people like therapists, for example. Another criticism is that restorative justice doesn’t really address the fundamental power structures that often lead to harm. Power dynamics are a concern in the restorative process – things like race and gender and age and class and sexual orientation don’t go away just because the restorative justice process is happening. Nor does social context, especially for kids, which may ultimately lead the harmed party to feel pressured into resolution before they feel ready.

Josie: Restorative justice isn’t perfect, and maybe it’s not for everyone or for every type of harm that’s been done. As we said, there’s no one solution to this disaster of the criminal justice system that we’ve created. But in general, restorative justice does offer a different way to think about harm, healing, restitution and consequences.

Josie: And fundamentally, it does attempt to rethink how we imagine punishment, which is key for any deeply rooted, real change to our criminal justice system. Here’s Danielle Sered talking once more on the difference between punishment and accountability.

[Begin Clip]

Danielle Sered: In our culture when we say accountability we usually mean punishment. But I understand that the two are not only different I actually believe that they’re incompatible. So punishment is passive. Like punishment is something somebody does to us. All we have to do to be punished is to not escape it. It doesn’t require anything in terms of our agency. It doesn’t require us to work. It doesn’t require us to acknowledge anything. It is something that is inflicted upon us by somebody else. Accountability is different. Accountability is active. At Common Justice we believe accountability has a few key elements. It requires that you acknowledge what you have done, that you acknowledge its impact on others, that you express genuine remorse, that you make things right to the degree possible, ideally in a way defined by those who were harmed and that you do the extraordinary hard labor of becoming someone who will never cause that kind of harm again. That kind of accountability is some of the most difficult labor any of us will do. And it’s not only harder than punishment, it’s also more effective, both for the person who caused harm, because it actually animates transformation, but essentially also for the person who was harmed because it actually answers to their pain and their needs. The problem with prison is that it makes almost no room for accountability whatsoever. People are separated from those they’ve harmed, they’re separated from those to whom they owe a debt, their ways of paying that debt, whether through something concrete like restitution or others things like paying forward their responsibility by being agents of positive change, are vastly constrained. And they’re in an environment that discourages honesty about what one has done and that dramatically constraints one’s ability to reflect deeply on the impact one has had on other people’s lives. And so prison not only doesn’t produce accountability, nothing about it does, but it interferes with it in such a way that it guts our ability as a society to actually hold accountability as a core value when something wrong has been done.

[End Clip]

Clint: You may remember from a previous episode this season, where our guest Abd’Allah Lateef, who was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for a crime he committed as a child, discussed his experience with the restorative justice process when he sat down and talked directly to the family of the person who was killed.

[Begin Clip]

Abd’Allah Lateef: When I had the opportunity to address some of the family members for the first time, I didn’t want to do it in open court… I asked their permission as to whether they would prefer that I do so in open court or privately… and they appreciated that candor and asked that it will be done in private. And I had a wonderful judge who ultimately afforded us his chambers. And a long story short, we had an opportunity to really share and open up and have a moment of honesty, candor, and vulnerability.

Clint: Wow.

Abd’Allah Lateef: And in that moment, everything that I said was exactly what they needed to hear decades earlier. So where they were up to that moment opposed to my resentencing because they didn’t know what my sentiment was, they didn’t know how I felt. Hearing it in the first person, for the first time, 30 something years later changed the entire mood of not just the hearing, but it was healing. A moment of healing for those who were directly impacted and that could have been facilitated decades earlier if it wasn’t for policies, practices and unnecessary adversarial decision making that goes on between district attorneys and defense attorneys and sometimes judges that inhibit that ability to move forward any type of restorative justice practices even when family members are most in need of that.

[End Clip]

Clint: Here to discuss this with us is Sonya Shah, an expert on the process of restorative justice and an Associate Professor at the California Institute of Integral Studies. Stay tuned.

[Music]

Josie: Thank you so much Sonya for joining us today. We’re so excited to talk to you.

Sonya Shah: Thank for having me.

Josie: So we’re talking today about restorative justice and I wanted you to first just tell us a little bit about what you do and how you got involved in this issue.

Sonya Shah: Yeah so I really got involved in restorative justice first and foremost from a really personal place. When I was young, I grew up in New York, my parents emigrated from India and left everything behind. And when we moved to New York, sort of treated New York like it was a small village even though it was the big town of Manhattan. And in that context of moving from another country and not really knowing the environment very well, I was in a situation of child sexual abuse by a caretaker. And I grew up, sort of my first, you know, 18 years, I didn’t really, I didn’t have a lot of memory about it. I was really scared, pretty terrified kid. And when I got to college, I sort of remembered everything and started a process of really healing and dealing with what had happened in my early childhood. And it was through that process that I had always kind of felt and come to realize that I wouldn’t have wanted a punitive outcome for the person that did the harm, that I would have really wanted to just know why they felt the need to do that and what was going on in their life and what kind of ways that I could have that kind of dialogue and conversation with them about the harm that they caused and the impact that it had. And I knew that because I felt that way, I knew that there were probably other victims and survivors who probably also felt the same way, survivors who don’t necessarily want punitive outcomes or believe in incarceration. And I think that was my personal journey. And then from there, clearly getting really politicized as a person of color, knowing that mass incarceration, incarceration is a very racialized system and not really believing that that is the way that we actually have true healing and accountability. That’s not the way that we’re going to actually transform a world without harm and violence. But we have to do it in a different way.

Clint: Did you always have this sense of healing and restoration taking precedent over a more punitive impulse or is it that something that you had to come to over time? Was it a sense, was it, you know, cause part of the thing that I always think about is that we live in and have all been raised in, in uh, not only just as society, but a world that is incredibly punitive and that tells us that when some type of harm, emotional, physical or otherwise is done to us, or done to someone we care about, that the way to achieve justice is through punitive means. And I can, I can speak for myself. I think it took me a long time to unlearn the sense of punitiveness that is a sort of ubiquitous fixture in our society and to move to a space where I thought of the response to harm being restoration rather than punishment. And I’m curious how that happened in relationship to the, the harm that you personally experienced.

Sonya Shah: Thanks for that question. Um, so I think that there’s like always four or five or six like complex really, really, really, why, is the reason that I do this work or believe this way or have a more restorative approach versus a maybe a punitive approach or a question you’d ask anyone, you know, and my first response is kind of a more personal one. I would say another reason for me is really deeply than I come from South Asia, I come from India, we’re first generation Indian Americans and my entire ancestry is from India and all of my immediate family members grew up through the British Raj and grew up through the Gandhian movement. And that movement was all about what does justice look like? Not by necessarily through violence, but through alternative means. It didn’t mean that it wasn’t forceful, it didn’t mean that it wasn’t really politicized and really activated. But what does it mean to actually not do harm while you are trying to get justice? And I think there’s like a deep ideology there that came very much from my familial cultural, ancestral background. And then I think as time progressed along the way and the more that I understood, the more I experienced, the more I felt, the more I got involved in this work, the more, you know, I started doing a lot of work about 15 years ago with people who were, uh, done severe harm and experienced severe harm and it, you know, time and time again, 99% of the time, it wasn’t as though someone who had done harm was ever born to do harm, you know, was born to create such havoc in someone else’s lives. But through a series of circumstances, through a series of traumatic experiences, through a series of just historical experiences, economic social experiences, if there are people of color, you know, found themselves at the bottom of being in the worst place of their lives at the worst time without a lot of opportunity or a lot of people around them to catch them and then created the kind of violence that they created. So how do we understand that and how did I? So it was really, really deeply experiential through the process of just being with folks that did a lot of harm and had experienced a lot of harm that I felt more and more like, this is not the way, this is not the way. Being punitive is not the way, it just hardens the heart. It creates more harm. It doesn’t actually change the system. If we’re talking about truly breaking legacies of violence, we’re not just talking about recidivism, we’re not just talking about emptying beds from prisons, we’re talking about creating an entire culture where we’re actually trying to address, interrupt, eradicate violence, than we have to think about what’s deeply at the, at the center of why it happens.

Josie: You just began talking about your work and working with people who have inflicted harm on others, working with survivors. Can you talk a little bit more about the work that you’ve done in restorative justice, around restorative justice and tell us more about the process?

Sonya Shah: For sure. So restorative justice is really about being a community based solution to dealing with harm and violence when it occurs. And that’s completely the opposite of our criminal justice system, the retributive system, which is basically a lock them up and throw away the key approach where no one really cares about what happened to the victim. They’re just used for conviction and no one really cares about what happened to the person that did the harm. The most traditional adversarial system and district attorney is just out for a conviction. So we’re going from that retributive system to a more restorative system. I will say my experience has been that like why, survivors don’t have to want to do restorative justice. There’s no like, we need to do this, it’s mandatory or even transformative justice, right? The question is really about providing another opportunity for those people that have experienced harm to say, you know, ‘I don’t really believe in this punitive system. That’s not what I wanted. Nobody, that’s actually not my healing, my healing and a part of my healing journey would be to actually sit face to face or sit in a circle with the person that harmed me and actually have a conversation. Come up with a plan, come up with ways that that harm can be addressed and quote unquote “repaired.”’ We know that things never actually get repaired, but the idea of what’s the kind of restoration that could be possible? And that’s really at the heart of different kinds of restorative justice processes from the survivor perspective. And I’ve met all kinds of survivors, survivors that wake up have been knocked unconscious from deep physical attacks who have woken up in spontaneous forgiveness. And I know survivors who’ve advocated for the death penalty. And so there’s no one way, one path for any survivor. We just want to create another option, another avenue, and for people who’ve done harm, you know, it’s really kind of unwinding the really, really deep cause of the cause of the cause of why I got to the point where I was able to commit a murder, a rape, a sexual abuse, a series of robberies, a lifetime of crime that I didn’t get caught for. Why was I able to do that? How did I get to that point? And there’s this process of unwinding, like, you know, childhood trauma, environmental factors, historical oppression, to look at one’s life experience, to be able to connect the dots of one’s own life to get to what was that moment in time and why at that moment in time did I commit that crime? And that journey is a huge journey of healing one’s own really difficult victimized life experiences and at the same time being accountable for the impact of the action that they created and being able to separate the difference between the two and being able to separate the difference between a person and an action so that a person is not the worst thing that they ever did. It’s an action that they did that was pretty horrible and tragic, but that’s not who they are. And I think it’s just like these very long journeys that are really, they are deeply rooted in healing that lead to, for people that did harm, some of the most accountable places that they can go and then the possibility of the dialogue between the two.

Clint: So I can imagine a scenario in which some, I don’t even, I don’t have to imagine it because this is responses that I’ve heard, but thinking about what you’ve laid out and the process of restoration and how the process of restoration is often a long one and a difficult one, and one that involves unpacking layers and layers of both personal micro histories and sort of larger macro histories. And I have heard people say ‘that’s fine, that healing should happen, but that healing should happen while the person is in prison and not in a separate context,’ right? They might say, ‘because there’s always this tension or perceived tension between the process of rehabilitation or restoration and healing and public safety,’ right? And so I’m curious how you would respond to someone who might contend that the processes you have in mind are good, but that those processes should take place in the context of an incarcerated space for someone who may not have gotten to the place of healing yet. And so, so how do you think about the relationship between the physicality of an incarcerated space and the process of healing and does healing necessitate that the person is not in such a space? Or, what is the relationship between the two of those things?

Sonya Shah: That’s like the million dollar question, right? And so I have a million things to say about that. So-

Clint: Yeah say them all.

Sonya Shah: Yeah. So here’s the thing. So firstly, prisons are now a part of our kind of collective consciousness, but we created that, right? If we think about the history of prisons in the United States, and I think California is a really great example to look at, Angela Davis’ Are Prisons Obsolete? is just a beautiful book about the history of the evolution of prisons. And in California there were only nine prisons built in hundreds of years until something like 1980 and from 1980 to now there’s been something like 33 prisons and 30 camps and five, you know, women’s incarcerated with their children facilities and some number close to 70 or 80 correctional facilities. So in 35 years we’ve built 80 facilities. And if we take the history of California, you know, it happened during Reagan’s administration with economic incentive to buy up rural, underappreciated rural land and to say, ‘hey, if we build these supermax or max prisons on this land, we create an industry, we create an economy.’ And from that economy, you know, California will boom and we’ll have these prison towns and etcetera, etcetera. And so then with that we have new prisons, then we have a whole economic system, the prison industrial complex, all the companies that are then benefiting from prison labor that keep it in place. And then we have the moral argument of criminality and equating people of color with being criminals that has to create an industry of prison. So we created all of it in 38 years. We have, in my lifetime, I’m 45 years old, in my lifetime, we created the notion of criminality and incarceration. So if we created it, we have an incredible opportunity to undo it, right? It just takes the unwinding of the collective consciousness to have a new collective consciousness. And with people like, you know, the Michelle Alexander’s of the world and all of the opening up of the penal codes and Supreme Court rulings and Angela Davis’ that’s what, that’s what’s happening. So I think that’s number one is just like really a deep recognition how much prison is a social cultural norm that has only been created in the last 35 years. So number one. Number two is of course when somebody does a harm, there’s like steps, right? It would be a little ridiculous to say that the minute somebody is beating someone else up that we should just like stop and offer everybody a restorative process. Clearly there’s like activation happening. There’s all kinds of things going on for the person who’s the survivor and the person who’s done the harm. So there’s definitely something about a period of time away, right? A time away from each other. That doesn’t have to look like a prison. It doesn’t have to look like a punitive time away. It could look very differently. Norway has the, as as an example of a time away, I’ll give you another example of a small community in Yukon territory in Northern Canada, the Heiltsuk Nation, they have a town of 1,600 people. I met the woman who runs the restorative justice center there, and she said, what they do is they have a cabin in the woods and basically when there’s a harm that happens, they ask the person to go to a cabin in the woods, that cabin in the woods, for one month to nine months, in that time, they’re visited by mentors. And um, what she said is they’re also like really having to heal and be in nature and with themselves. And she said that there’s just something incredible that happens when you have to confront yourself in nature and how that kind of healing and accountability has taken place and the way people have come back from their one month to nine months to then be accountable to the community that they harmed. So that’s an example, right? Um, there’s so, so what would be our version of, what would be the urban version of a cabin in the woods? What would be a version of creating public safety that doesn’t look like isolation and a punitive response?

Clint: Even though I do like this idea of making everyone into a transcendentalist.

Josie: (Laughs.)

Sonya Shah: (Laughs.) Yeah. Exactly. You know, we have to create and be very creative about what our versions look like and I think that that’s definitely, of course there’s time away. Of course there’s removing people from a situation that’s bad for both people. A lot of times I think what people don’t recognize is if someone’s doing harm, they’re also coming from an environment where that’s like kind of what’s going on and to think that they can just go back to their environment and then just be like, ‘yeah, I’ve transformed, I’ve changed,’ but my environment is exactly the same. How can that person live out transformation if they’re back in their same environment sometimes. Right? So like thinking through all of the things that actually need to take place in order for us to truly get to the place where we’re meeting the needs of public safety and meeting the needs of people who have committed an act of violence. I want to give one other example, which I know people kind of use as this weird pie in the sky example, but I also met another, a woman from the Nisga’a Nation, also from Canada, who in their community and their indigenous community, when there’s domestic violence for example, what she said they do is they bring everyone together, all the families together. The elders speak first, actually what she said, what happens first is that they tell the couple everything that is good about them, everything that they remember about them, everything that is, you know, that they’ve ever done, that’s really amazing and positive. And then the elders speak and then the family speaks and then the couple of speak. And I see that because, you know, there is this kind of like example that’s out there about like, ‘oh, there are these tribes that do that,’ but there are actually real people who do that, you know, and that do first start with trying to have us remember what’s good about ourselves. You know what we can be proud of before we get to how we actually hurt and harmed each other. That’s the way that community deals with harm when it happens.

Josie: You know, one of the things that I think is really interesting about your work is that you have been doing this work directly, meaning you’ve actually, you know, this is not just theoretical, right? You’ve seen people go through this process. You yourself has gone through this process and I imagine that when you understood that you wanted some sort of reconciliation for your own harm without it necessarily being punitive, at that time did you have a name for restorative justice or did you just know that you wanted something?

Sonya Shah: You’re totally right. I think most people have some feeling or experience of quote unquote “restorative justice” before they ever come across the term, which is just the impulse towards restoration and reconciliation, right? There’s some like, ‘oh yeah, I’ve experienced something like that. I want to talk to the person. I don’t want other people to be involved. I want to work this out.’ Right? So I definitely feel like I’ve had that. There’s also like really two roots and origins to restorative justice. One is an indigenous one, you know, which is not to pan-indigenize everybody, but there are many different examples from the Maori, from the Yukon folks, from many different places of people who have found ways to sit in circle or to come up with processes that are about dealing with harm when it happens. And then there’s the restorative justice that really kind of got birthed like in the ‘80s through responses to the criminal, a real feeling of a broken criminal legal system that is what I explained before, right? Where we have a criminal legal system that’s retributive that only asks, you know, what law was broken, who broke it and how do we punish them? And what restorative justice asks and this is from Howard Zehr’s work, who was a Mennonite: What happened? Who was harmed? What are the needs of the person that’s harmed? What’s the responsibility to repair the harm? What were the causes and conditions in which those harms happened? So those are kind of the, you know, just to kind of highlight where restorative justice comes from. But when I’ve done trainings and talked, you know, many people who’ve never heard of it, will come up with, ‘oh yeah, when I was, you know, 20 or when we did this or we did that, you know, we used to do circle or restorative justice.’ So I think there’s something about a remembering that we could have in our imagination about not using the state. Right? Like what did it look like before we had so much reliance on institutions and states? And just like almost so much that we think it’s in our blood, you know, to go to the state, you know, as opposed to go to the principal, tell your boss. Right? Any of those are punitive responses as opposed to like taking care of it myself or take care of it in my community. So that’s what I would say to that.

Josie: After doing this for so many years, what are some of the strongest memories you have in this work and in terms of the people that you’ve worked with, the stories you’ve seen, the repair you’ve been part of, or even the times that it was less successful?

Sonya Shah: So I have had a few situations working with people who’ve done severe harm where folks have done like, not just one crime, but we’ll have said after months and months of working together, ‘yeah, actually I did like a hundred, 200, 300 robberies. I used to break and enter, like I did it for 10 years.’ Right? So we’re talking about like a lifetime of crime, you know, and came into sitting in like a circle with arms crossed and like this is stupid and you know, whatever and like, why should I trust you? And just through the process of, usually it’s time and the depth of relationship that that kind of feeling changes, right? Time, depth of relationship and kind of the depth of work as well as being in a group of people that have also committed similar crimes that are willing to like go there and talk about them and work through shame and trauma and guilt and remorse and, you know, all of the things that need to get worked through. And I have seen more than one time, um, these very gradual softenings, thawings, tears start happening and light bulbs go off and just an incredible sense of like, ‘wow, I did that and I really like don’t really ever want to be there again.’ And think those moments have been the reason why I do this work. You know what I mean? To just sit with somebody in their own process of recognition of like all the horrible things that happened to them and all the horrible things that they might’ve done. And one of the things I would say, two things I would say that her incredibly critical to like creating the conditions for accountability are, one, most people haven’t felt seen or heard or empathized with in their own pain and suffering and trauma. So, so much of this process is just about sitting with somebody in their own pain and suffering and trauma before getting to like why they did the harm. And the second thing is healing really happens in relationship, right? Accountability happens in relationship. So the way in which like in a community based healing modality, watching other people go through sharing really hard, painful things, dealing with their shame is probably one of the number one reasons that people who’ve had the hardest time talking about their crimes have been able to because they’ve said ‘I was going to come in here and I was going to just, you know, blah blah blah my way through but then I was like, I was listening to everybody speak and I have so much respect for X, Y, and Z and there came a point where I just couldn’t do it because I respect this person so much.’ So one thing that people might not realize is that responsibility to others can actually help with accountability and even recidivism. There’s another great example of a woman from the Navajo Nation who’s a peace builder and what she said to me was that when people who have recidivated come to her and she’s working with them, the first thing that she does is she helps to name clanship and kinship. And once you’re naming your relations, ‘so this is my uncle, this is my brother, this is my sister, my nephew, my niece,’ she said it’s like the sense of responsibility and belonging creates accountability and a desire not to harm again. And I want to say, as a personal example, that was true for me when I was in, I grew up in New York, I think I shoplifted from when I was 15 to 21 I went to Brown University, I shoplifted all four years through Brown University and no joke, I went to an ivy league and I was a shoplifter and then I came home and I worked in a junior high school. It was a charter school and I worked for my junior high school history teacher who was the only African American female in the district. And she loved me to death and I loved those kids and they were all having problems. And I remember being at a Duane Reade and like going to shoplift something, I didn’t need to do it, you know, there was no reason. I was just like, it was like this behavior thing that I was doing because I couldn’t deal with my life for most of my teenage hood and my college years and then I remember the day stopped. I thought of those kids, my kids and my seventh and eighth grade class and I was like, ‘I will never live it down if they see me here, you know, doing what I’m doing right now.’ And then since 21 I never shoplifted again.

Josie: Right, right.

Sonya Shah: And I’m 45 so 24 years of shoplifting free. But that’s a very real example of what does it mean? Like we think it’s all like we just have to do it ourselves and it’s all like deep personal healing. No, it’s also about our responsibility to family, to community, to like others that can help accountability happen.

Josie: Yeah. I do think that when people feel responsible for other people, but also just necessary, right? That their presence means something, that they have value, to me, that is such a better deterrent then physically torturing people and hoping that changes them.

Sonya Shah: Yep. Just another story as we’re doing-

Josie: Yeah, please.

Sonya Shah: Yeah. Right now I’m doing a victim offender dialogue with a woman who was sexually abused by her stepfather and over, you know, many, many years and her just incredible tenacity and her desire to just like speak to him directly and know why and like really get to hearing it from him that it was true and feel validated. It’s just such a deep healing experience for that survivor. And I’m, I’m thinking about one of her desires is she’s a parent and how some kids who are, you know, preteens and is terrified of them going outside and being away from the house. And what she really wants for herself as an outcome is to feel safer in her kid’s going out, you know, and going out for sleepovers and stuff like that. And, you know, so it’s just like that kind of, um, being with someone like that, you know, who has a desire to heal so desperately. It’s like the human resiliency of it is unbelievable. And the person that did the harm, who really truly knows that he did it and his wants to participate in that healing journey for, you know, her and of course also for himself is very, very powerful.

Clint: I’m curious what spaces you find yourself doing this work in? What are the sort of different dynamics that shape what the process of restorative justice looks like in each, we talked a little bit about the sort of desire to, to pull it away from operating within the state, but I’m curious like in school, in community organizations, in somebody’s kitchen, whereas a lot of this happening and how does the place that it happens and that sort of way shape what the process looks like?

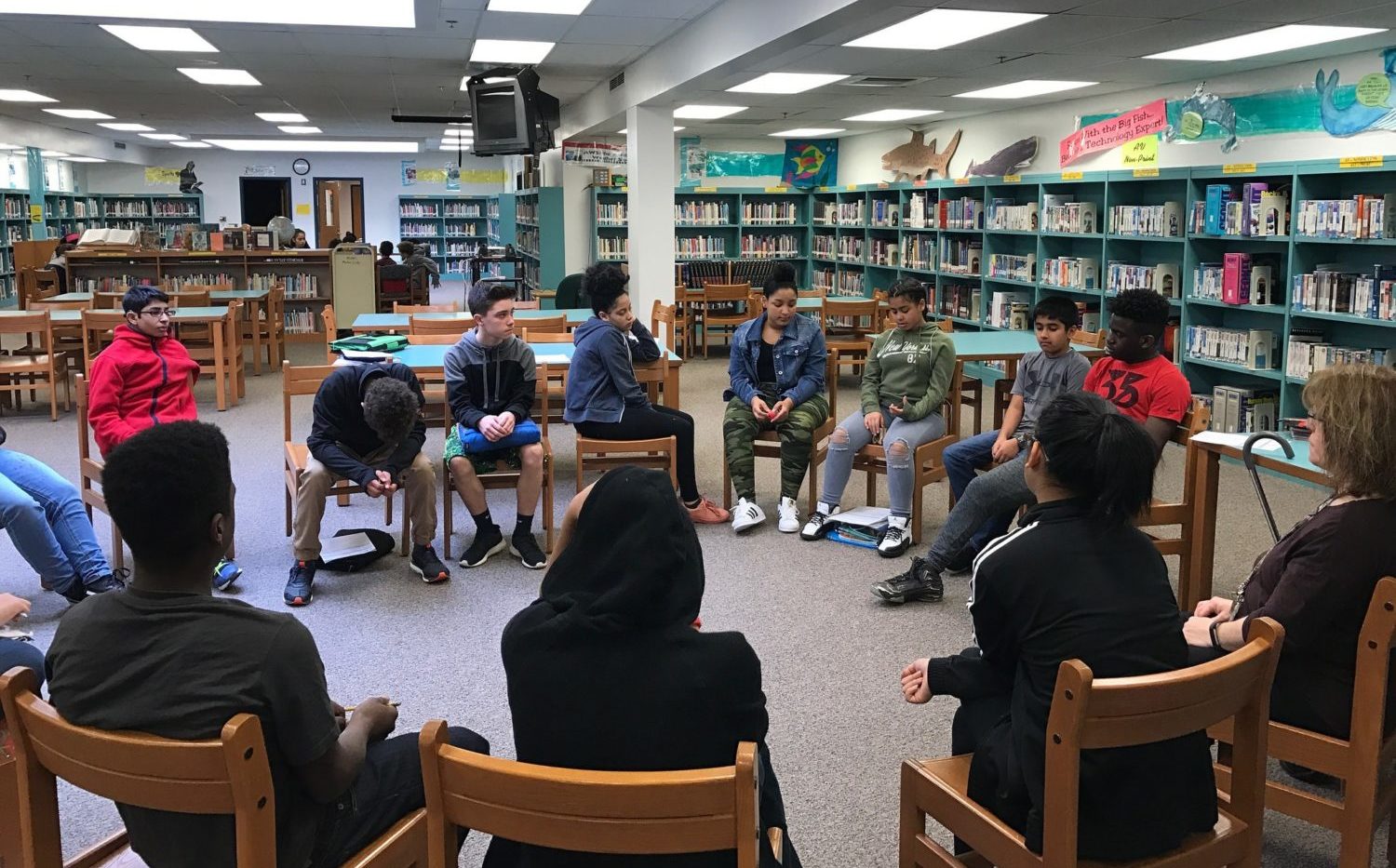

Sonya Shah: Yeah, so there’s a huge budding restorative justice movement in schools for sure. I think that, so I guess another story is useful, but, and I, and I’ll tell sort of an Oakland based story. So maybe about 10 ago there was a woman named Rita Alfred and she, you know, took a circle process training and she was a disciplinary hearing officer for the Oakland School District and decided after that training, you know, I really want to try something different. So she went into a West Oakland middle school and in the first year in the school, she taught all the principals and staffs how to do circle process RJ-style. And then in the second year she taught all the kids. And in two years, this was studied by the Henderson Center for Social Justice at Berkeley this school that was in West Oakland that was, you know, had high suspension and expulsion rate, lots of kids of color, the expulsion rate went to zero and the suspension rate went down 75 percent.

Clint: Wow.

Sonya Shah: And this is consistent. So this is 10 years ago, right? So boom. So this happens and it’s happening all over. It’s happening in Pennsylvania. It’s happening in Colorado. It’s happening in Minnesota. And slowly and gradually it catches on. And a lot of these school boards in different states have adopted restorative practices as a way to do discipline. Meaning that instead of, you know, having a suspension expulsion kind of punitive system decided by the vice principal, you go to a restorative process, um, which pulls in parents and teachers and principals and kids and all of that kind of stuff. And the statistics across the board in all of these states are the same that somewhere in between, if you offer restorative practices as a process, that expulsion rate and suspension rates have gone down between like 56 to 85 percent depending on what school. Right? And now when we’re talking about kids of color and we’re talking about the school to prison pipeline, we know how important it is to actually bring down suspension and expulsion rates in these particular situations. So the school’s movement is huge. Of course like anything as it gets big, there can be like some processes that get more eroded where, you know, if not trained well, restorative justice becomes another kind of scripted tool that some teacher is slapped with doing and has no idea that it’s really like a paradigm shift of how you think about harm. So when it’s not done well, it’s replicating like something harmful and that has happened and when it is done well it’s because the restorative justice coordinator has internalized a different paradigm. The school is internalizing a different way to think about discipline, to think about like not discipline but even like when harm is happening around you and like the health of kids. Right? So it’s like most of the training that happens around how to do RJ in schools is really about taking a whole school approach and not saying like don’t be just that teacher or that one person out there in the school who’s trying to do it differently. You need the whole school on board. So that’s a big piece on the school’s thing. And the person that I’m close to who runs the Oakland Unified School District program, he has often said like for, we have 33 restorative justice coordinators in the Oakland schools, which are sadly on the chopping block right now, but that’s another story because of the city budget, but anyway, so he has said that basically 90 percent of doing restorative work in schools is community building. 90 percent of the time all you’re doing is being in circle, building, community building relationship and it is so that when the 10 percent of when you know the stuff hits the fan happens, that folks are ready, they’re ready to deal with the harm when it happens. Right? But you have to do that 90 percent of your time is community building and relationship building. So that’s very much how this work is being infused kind of in the schools context. Also, there’s a really large contingent of folks that are trying to do what’s called restorative community conferencing. So it’s like diversion for young people who do harm out of any juvenile justice system. So we know that if a young person, you know, at 16 to 20 touches, you know, the juvenile justice system, is incarcerated, they are like 90 percent likely to go into an adult system. We also know that because of all of the research, all his stats, everything, that like there’s like this spike of crime of like harm that happens at the age of particularly boys between the age of like 16 and 20. So it’s like what do we do to, what do we need to do to get young boys, probably mainly more young boys of color through that age? Right? So how can we divert them out of the juvenile justice system? What restorative community conferences are, are basically working with the whole community, you know, to refer cases to an outside system and then solving it before it ever goes to juvenile justice. Or if they go to the court, working with the DAs to divert the cases to an outside organization and have everybody on board to say, ‘if you go through this restorative community conference process and come up with a plan, you will never, your case is closed.’ You know, ‘if you fulfill the plan, it’s done and you never touch the system.’ So that restorative community conferencing and diversion program is alive and well. It’s something that started in New Zealand and has been happening in Baltimore with a program that Lauren Abramson started and is now rooted in Baltimore, I think it’s Restorative Response Baltimore, with Sujata Baliga’s work, uh, here in Oakland, with, I know folks like Wakumi Douglas in Florida and Travis Claybrook in Tennessee and you know, they’re all these different places that are trying to do the diversion work and it has proven to actually work from the New Zealand context and is proven to now be working here.

Josie: Great. This is so good. I do want to say quickly that for people listening, the story you mentioned about the Oakland restorative justice program in the schools and how it’s on the chopping block, there’s actually a good article about that on The Appeal. So, we’re not talking about it today on the show, but you should check out what’s happening because it is such an important program and to lose it, it would be really tragic. I guess I’d want to understand from you, over all these years of doing this work, what are some of the kind of benefits or the like lessons learned that have surprised you in that you think would surprise people who are listening? Because I think describing restorative justice, people are like, ‘oh, okay, that sounds like good and like it could work,’ right? But then when you actually see it every day, I think it’s just such a deeper, bigger result than you can even imagine or at least that’s been my experience in the little restorative justice work I’ve, I’ve seen personally and so I’d just love to hear from you, as someone who’s doing this day in and day out, what are you taking from this continually as you keep doing this work?

Sonya Shah: Yeah, no, it’s a great question. I mean I think, you know what I said sort of as we ended is that this is really about, in order to do kind of restorative justice work or transformative justice work you have to really internalize a paradigm shift, you have to internalize like that we truly can build a network, build the relationships with each other to actually deal with harm when it happens. Like it is actually possible. And maybe because there’s such a intense sort of Goliath of an adversarial system, of a system that tells you to go punish, what we see is just like these like sparking evidence and these like micro examples of like one on one dialogues or one case that happened or one restorative impulse to do it differently. And so it’s like, you know, this smattering of like the flower that’s coming through the cracks in the sidewalk that’s like just wanting to burst through and it takes a lot of water and belief, you know? And it really takes us to change our collective imagination of what is possible in order to actually bring restorative justice to scale. You actually have to believe it’s true. You know that it’s possible and we can’t convince people that it’s true unless they actually probably experience it. Right? So there’s also something about going into those situations where you’re also like allowing yourself to say like, ‘okay, the next time I am involved with some sort of harm that happens, I’m going to actually try to do this differently whether I did harm, I was in it or I witnessed it,’ you know, and what does that going to look like? How am I going to do that? So I think that that’s a big takeaway for me. Another thing that I’ve been thinking a lot more about is just I think, um, it’s really interesting to look at the work of like transformative justice, particularly the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective has something called Pod Mapping and they sort of imagine this idea that if we’re actually going to create a world where we do draw on each other, then we need to create a ridiculously strong sense of community. And we need to figure out what they call pods. Like create pods, create community. You know, so many people feel so isolated, like they have no one to draw on both when they’ve been victimized and also when they’ve done harm. But what if we are creating pods of people that are like, ‘okay, if I do something harmful, I’m, these are my people I’m going to call on to hold me accountable and if I need help these are the people I’m going to draw on.’ And this is a very, very deep notion of what does it mean to actually try to not just to move out of the microcase. You know what I mean? Into like the community response. And I think that that’s really, that’s going to take a lot of us kind of believing that it is true. And it’s really hard because we don’t have, you know, we don’t necessarily have the examples sitting right in front of us and there’s so much, there’s so much about this sort of capitalist, patriarchal, modernity, you know, racist system that’s telling us to do it the other way.

Josie: Right.

Clint: Well this has been fantastic and so helpful and so illuminating. We just really want to thank you for taking the time and thank you for the work you do more than anything.

Josie: Yeah. This is so great Sonya. Thank you so much.

Sonya Shah: Thank you. Thank you for the work you do.

[Music]

Josie: Thank you so much to Sonya Shah for joining us today and we also want to thank you Danielle Sered for her contributions to this episode.

Clint: And thank you all as always for listening to Justice in America. I’m Clint Smith.

Josie: I’m Josie Duffy Rice.

Clint: You can find us on Twitter @justice_podcast, like our Facebook page at Justice in America and subscribe and rate us on iTunes, it really helps.

Josie: Justice in America is produced by Florence Barrau-Adams, the production assistant is Trendel Lightburn with location recording by Jon Kalish and Natalie Jones. Hope you Join us next week for our last episode of the season.

[Music]