Just 6% of Columbus Police Officers Account for Half of All Force Reports

Between 2001 and 2017, the department justified officers in 99 percent of use-of-force cases, according to data released through a public records request.

On the evening of Sept. 14, 2016, Columbus police officers picked up a robbery call. The victim said he was robbed by a group of teenagers, and that one of them had a pistol. “I’m not going to mess with it over $10,” he told the dispatcher. The cops who responded to the complaint spotted three teenagers. Two escaped on foot, but the officers cornered the third, Tyre King, a Black 13-year-old, in an alley. Cops claimed King then pulled out what they thought was a gun from his waistband. King’s friend claimed he was running away. Bryan C. Mason, a white officer, fired multiple times, killing the child. An autopsy, requested by King’s family, found that he was “more likely than not” running away when he was shot three times.

After the shooting, local media outlets pointed out that Mason, a nine-year veteran of the department, had either met or exceeded expectations in all departmental job review categories and received several letters of commendation and awards. But there were also clear warning signs.

In the seven years prior to the shooting, Mason had been the subject of 47 reports involving force, according to a database of internal affairs investigations obtained by The Appeal. Four of those reports stemmed from previous officer-involved shootings, two of which were fatal. According to Reuters, 25 of these force incidents resulted in civilians requiring medical attention. Weeks after the killing, Mason returned to the department, placed on desk duty. The next year a grand jury declined to indict Mason for his actions.

Mason’s force report numbers land him among a small core of officers who account for a disproportionate amount of the alleged violence reported to Columbus’s internal affairs bureau by officers and civilians.

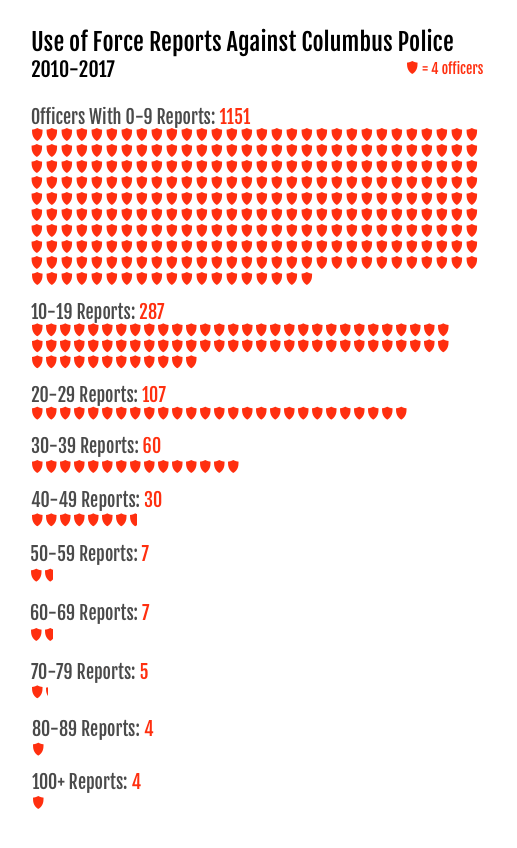

Between 2001 and 2014, the years where Columbus police data is most complete, an Appeal analysis found that on average just 6.28 percent of sworn police personnel in Columbus have accounted for half of force cases annually. The dataset, which includes incidents self-reported by officers to internal affairs as well as civilian complaints, spanned 20,118 use-of-force investigations. More than 3,000 of those cases arose from civilian complaints. Of the more than 20,000 investigations just 152, 0.75 percent, were sustained or found in violation of policy, between 2001 and 2017. More than 97 percent of civilian-generated complaints were ruled “unfounded” or “exonerated,” meaning investigators concluded that the officer’s actions did not violate policy.

This high number of exonerated and unfounded complaints suggests “there’s something wrong,” said Norm Stamper, a former Seattle police chief and a national expert on police misconduct. “That’s an organization that systematically tolerates abuse.”

Why the 6% remain in the ranks

The officers with large numbers of force incidents remain in place because “aggressive” behavior is valued more than their neighborhood reputation, four current Columbus police officers told The Appeal. The officers say that aggressive stop-and-search tactics accomplish short term goals for the department, such as felony arrests and gun or drug seizures, but inevitably lead to violent encounters, which erode civilians’ relationships with officers.

“A lot of officers actually think you’re only a good officer if you do generate complaints,” said one officer, who requested anonymity citing fears of professional reprisal. “If you have an officer who just likes talking calls for service, he’s considered lazy because he’s not getting tons of felony arrests. But if you’re known for getting lots of felony arrests, the force is fine, because you’re getting busy, you’re getting at it.”

The department declined to comment for this article.

Mason’s history in the department suggests that aggressive behavior doesn’t slow down officers’ careers. Just over a year after joining the department, he received departmental recognition for his participation in the division’s Summer Strike Force, an aggressive plainclothes squad which went after guns. Soon after, his force reports and shootings began.

In 2009, Mason was involved in his first shooting, in which two officers were wounded and the suspect was killed. Over the next three years, he was the involved in 25 force-related incidents, culminating in a second shooting in December 2012, when he shot and killed a man who had called 911 on an intruder, after the man failed to respond to commands to drop the gun he was pointing at the intruder. Less than a year later, Mason shot and injured a man during a traffic stop. Between 2009 and 2015, Mason racked up an average of more than six reports a year involving force.

In all but one of his 47 force cases, Columbus police determined that the reports were “within policy” or “unfounded.” (As of 2017, one case was listed as pending.) Just two other officers in the dataset, Howard Brenner and Harry Vanfossan, have been involved in more shootings than Mason, and only 39 current or former officers have been the subject of more force investigations.

Mason’s history of force

Yet even after the shooting of Tyre King, which sparked national media coverage, Mason was not punished with a low-level desk job, officers noted. Instead, he was placed on narcotics duty, which officers told The Appeal was a coveted position.

And in the rare cases where officers are disciplined for alleged misconduct, their careers often rebound quickly. Officer Zachary Rosen, who was fired in 2017 after a video emerged of him stomping on the head of a man who was being handcuffed by Rosen’s partner, was reinstated by an arbitrator in March and granted a position as an investigator in the Columbus police division’s Strategic Response Bureau.

‘It’s just not taken seriously.’

The department’s use-of-force policy stipulates that officers are allowed to use force to effect an arrest and defend themselves or others, but that they may not use “more force than is reasonable in a particular incident.” Deadly force is permitted only when there is probable cause to believe the suspect poses an immediate threat or when it’s an “objectively reasonable” response to prevent imminent harm.

Yet so few force incident investigations hold cops accountable because the department chooses not to take them seriously, argued several officers.

“We tend to dehumanize people who commit crimes or violations,” said one officer, explaining why so few complaints get through.

“There has to be bias as far as who’s investigating the complaint,” said another officer. “It’s just not taken seriously.”

Some department leaders have their own history of force reports, another officer pointed out. As a lieutenant, Thomas Quinlan, now one of the department’s three deputy chiefs, had 11 force reports, all involving mace or other chemical agents. Before being promoted to Columbus zone commanders Jennifer Knight and Rhonda Grizzell were involved in 13 and 14 force-related incidents, respectively. Knight’s reports included nine cases involving mace, and Grizzell’s included multiple mace incidents and injuries to civilians during and after arrests. In every incident, internal affairs investigators ruled that Knight and Grizzell had not violated department policies. Before her move to zone commander, Knight was commander of Columbus’s Internal Affairs Bureau.

“If these commanders weren’t held accountable when they were coming up as sergeants and officers, why would they hold others accountable?” said the officer.

Departmental structures meant to ensure accountability have also been watered down by the Columbus police union’s contract.

Though the department, like many agencies, has a program in house to identify troubling behavior, the union’s contract prevents complaints deemed to be unfounded from being factored into disciplinary decisions. The system thus “doesn’t have teeth because so many of the complaints aren’t sustained,” said one officer.

When complaints are sustained, the union contract ensures that they won’t remain on an officer’s record for long. Except in cases involving insubordination or criminal behavior, the contract requires “progressive action,” meaning that an officer must be found in violation of policy at least three times before they can be suspended. Additionally, first-time violations cannot be used “for any administrative purpose” after one year, as long as the officer is not found in violation of any other policies during that time. Only 13 officers in the internal affairs dataset have had more than one force-related complaint sustained against them.

Beyond Columbus

The small number of problem officers generating large numbers of force incidents is not an issue isolated to Columbus, says Alex Vitale, a Brooklyn College sociology professor whose scholarship focuses on policing.

In many departments, the issue is compounded by a pervasive lack of accountability for problem officers. A recent BuzzFeed News investigation found that more than 300 NYPD officers who had been found guilty of fireable offenses like lying under oath, drunk driving or excessive force were instead able to keep the jobs without even a suspension. In 2017, Reuters found that the majority of police union contracts it examined contained provisions requiring departments to remove past offenses from officers’ disciplinary records, in some cases after just six months. Twenty of the contracts reviewed by Reuters allowed officers to forfeit vacation or sick time in lieu of a suspension, allowing them to “serve their time” without missing a day of work.

In cities across the country, Vitale notes that specialized plainclothes units, like the one Mason was in, tend to have more violent encounters.

“Police will say that’s to be expected, that’s why we created those units,” said Vitale. “But is that really is the best way to get guns off the street? Through the widespread abuse of very specific populations, subjected to stop and frisks, constant interventions. This is a sad state of affairs if this how we systematically treat some communities and not others.”

Baltimore, for example, disbanded its plainclothes units in 2017 after years of allegations of excessive force, planting evidence, drug trafficking, and eventually, criminal charges involving robbery, extortion, and gun sales. In New York, plainclothes officers have been involved in many of the city’s most high-profile incidents of police violence, including the 2014 killing of Eric Garner and the 1999 fatal shooting of Amadou Diallo. An analysis by The Intercept found that plainclothes officers account for nearly a third of all fatal NYPD shootings, despite comprising just 6 percent of the force.

Stamper, the former Seattle police chief, argued that police departments like Columbus often assume that citizen complaints are an inevitable part of their work. “One element of the system that I’m hearing described is the value system: performance evaluation based on a belief that cops who are doing their jobs are going to generate some heat. ‘Of course they’re going to get complaints because they’re doing police work,’” Stamper said. “I choose to see things very differently. I think most people, even those who are arrested, are able, once the adrenaline subsides, to make a reasoned judgment about the behavior of a police officer. If you have a police officer who generates complaint after complaint after complaint from citizens, you have a police officer who’s very much in need of discipline.”

The solution, Stamper said, starts with addressing the conflicts of interest that often plague internal affairs investigations. “Those kind of investigations, if they’re going to achieve the kind of public confidence and credibility that’s essential for basic fairness to all stakeholders, they’re just not going to happen until they’re independent and carried out by truly knowledgeable and skillful investigators, and that simply does not apply to most police departments today.”

The force incident numbers obtained by The Appeal most likely represent only a small fraction of alleged abuse incidents, Vitale warned. “There must be a low level of confidence in the system, which would inhibit people’s likelihood of filing complaints, which means the numbers aren’t an accurate reflection of what’s happening,” he said. “Obviously the Columbus police department is not learning from the data or taking these complaints seriously.”

Columbus police officers who spoke with The Appeal are skeptical that any serious institutional changes will be made to hold problem officers more accountable. “I don’t have any hope unless something major happens and they’re made to take a look at it,” said one officer.

A system that fails to take force incidents seriously could cause long-term distrust of police among residents in the long run, he said. “I’m not saying that sometimes citizens don’t make up things, but if we’re talking 6 percent then that’s a hundred officers who engage in that behavior,” said the officer. “The department’s failure to hold officers accountable for force incidents 99 percent of the time sends a message to the public. You’re saying, ‘This person doesn’t matter.’”