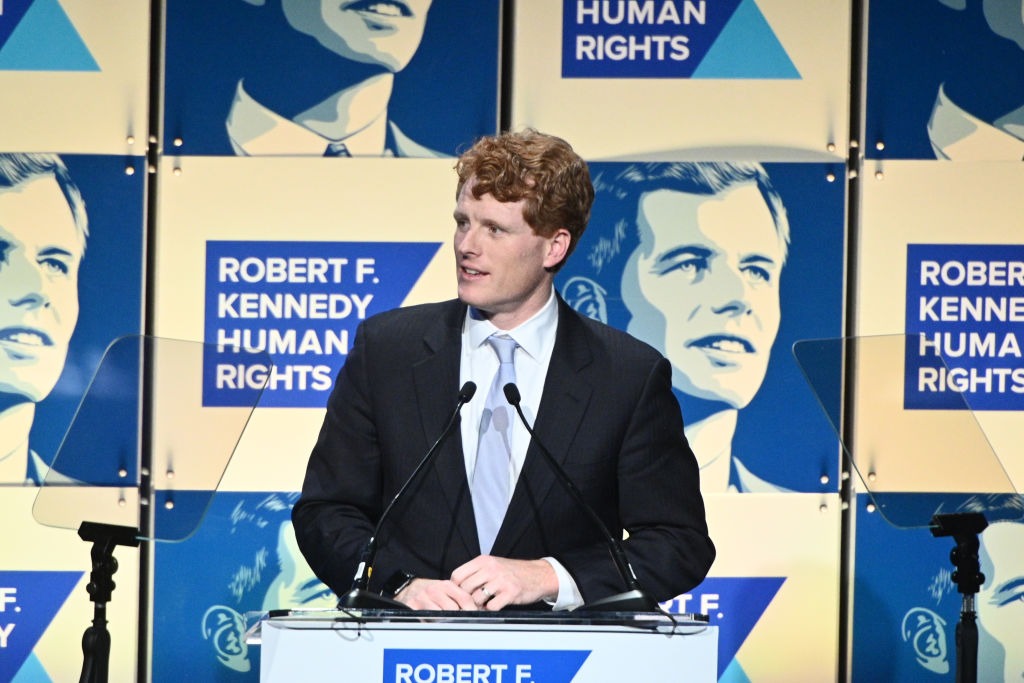

Joe Kennedy III Says He Is Running A Progressive Senate Campaign. But He Worked For One Of The Most Regressive D.A.s In Massachusetts

In his run for president, Mayor Pete Buttigieg has been forced to address his consulting past. Kennedy should do the same about his work.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis on important issues and actors in the criminal legal system.

In Massachusetts, U.S. Representative Joseph Kennedy III is mounting a seemingly progressive challenge to Democratic incumbent Ed Markey for his Senate seat, with a criminal justice platform that any reformer could love.

He has called for decriminalizing poverty, ending cash bail, expunging convictions for low-level drug offenses and a “dramatic reduction” in the use of mandatory minimums. He also reversed himself on the issue of marijuana decriminalization; Kennedy initially opposed Massachusetts’s 2016 ballot measure to legalize recreational marijuana. Two years after that measure’s passage, however, Kennedy called for marijuana to be removed from the Controlled Substances Act at the federal level. He also supported passage of the First Step Act, the only major criminal justice reform legislation to be enacted during his time in Congress.

These positions are certainly welcome, and consistent with the mainstream movement to reform prosecutors and the criminal legal system. But Kennedy has thus far remained silent about his own role in maintaining the system status quo that he now declares to be unacceptable. Before Kennedy was the purportedly progressive crusader challenging the Senate sponsor of the Green New Deal for his seat, he received an appointment to work as a prosecutor for district attorney of the Cape and Islands, Michael O’Keefe, one of only a small handful of elected Republicans in Massachusetts, and staunch opponent of even the mildest criminal justice reforms.

O’Keefe made news in May when he wrote a reactionary opinion piece in the Boston Globe criticizing what he called “social justice district attorneys.” It was a thinly veiled attack on Rachael Rollins, Boston’s then newly elected DA who pledged not to prosecute certain low level offenses. O’Keefe also wrote that prosecutors were blameless for “demographic inequities in the incarcerated population.” The real culprit, O’Keefe wrote, was “the disintegration of the family, a lack of respect for discipline and education, and the glorification in some communities of a culture that celebrates disrespectful language and misogyny under the guise of art.” He claimed that George Soros was the driving force behind “social justice candidates,” and described specialized drug and mental health sessions—programs administered by trial courts, not the DA’s office, to serve adults struggling with substance use disorder and mental health issues—as “our attempt to act in loco parentis for the dysfunctional members of society.” Contrary to O’Keefe’s infantilizing characterization, graduation from these programs requires months of work, intensive treatment, grit and determination.

O’Keefe’s piece was part of a career marked by a cavalier approach to ethics and an open contempt for attempts to improve the criminal legal system. He was first elected as district attorney for the Cape and Islands in 2002. The next year, he refused to recuse himself from a high-profile murder case after he was quoted making derogatory comments about the supposed sexual habits of the victim. In 2006, two judges were prohibited from hearing criminal cases in his jurisdiction after it was discovered that O’Keefe’s office paid $2,500 for one of them to attend a training conference. In 2010, he was also the subject of a federal probe for allegedly tipping off members of a gambling ring to an investigation. O’Keefe always denied wrongdoing, no charges were ever filed, and the inquiry apparently ended in 2012.

O’Keefe never met a form of criminal legal system reform that he didn’t hate. In 2012, he opposed a draconian three-strikes law for violent offenses not on its merits, but because it didn’t go far enough, and because it reduced sentencing for nonviolent drug crimes. “Once the Legislature stripped out the provisions of this crime bill which would have had an impact on public safety, this became a bill favoring criminals over the victims of crime,” he said. In 2017, O’Keefe said Massachusetts’s low incarceration rate “demonstrates the ‘thoughtful employment’ of mandatory minimum sentences by the state’s 11 district attorneys….despite all of the criticism, we’re really a model for the rest of the country.” (According to the Massachusetts Department of Correction, the Commonwealth’s incarcerated population increased by 9 percent between 2005 and 2014.) Two years earlier, he went even further, saying that mandatory minimum sentencing was tame considering other alternatives. “There are places in the world where their penalties for certain activities are much more draconian than incarceration.” he said. “For example, they kill people. They cut off the hands of people who deal drugs in certain parts of the world.”

After the Dookhan/Farak scandals, in which state crime lab technicians were found to have forged thousands of drug certifications resulting in Massachusetts throwing out more than 21,000 convictions, O’Keefe was reluctant to dismiss cases. He said: “We should keep in mind that we’re not dealing with actual innocence here. We’re dealing with drug defendants—the overwhelming majority of whom pled guilty. We believe that the integrity of our system of justice is more important than an individual conviction.” Along with Kennedy, O’Keefe also strongly opposed Massachusetts’s 2016 ballot measure legalizing marijuana.

O’Keefe is squarely in the camp of an old-school, law-and-order Republican DA. His rhetoric around the “disintegration of the family” and other issues in “some communities” recalls the racist report in 1965 from Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan that argued that America’s Black communities are a “tangle of pathology” and became a go-to document for law enforcement demagogues like former NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton. Which raises the question: Why did Joe Kennedy—scion to a name and fortune he did not ask for but certainly benefited from, and proud possessor of a brand new Harvard law degree—choose in 2009 to help cage his indigent neighbors under the leadership of O’Keefe?

This question is important because the movement for criminal legal reform has a history of electing people whose rhetoric doesn’t always match their record. Boston DA Rollins, target of Michael O’Keefe’s ire, has been criticized for failing to live up to her promises. Just as Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg was rightfully pressed to be forthright about the work he did for the consulting firm McKinsey, and how his time there shaped his views and policies, Kennedy owes it to voters to explain why he used his privilege to seek convictions for the most vulnerable members of his community. He must also address why he chose to do so as someone who now claims to oppose the law-and-order positions central to his former job with the DA’s office.

I asked Kennedy spokesperson Emily Kaufman about his work with O’Keefe, and what he thought of the Cape and Island DA’s long tenure and hardline positions on the criminal legal system. In an email, Kaufman wrote that “while Joe and D.A. O’Keefe disagree on plenty of politics and policy, particularly around criminal justice reform, Joe is grateful for the experience he had in that office. It was his time in the courts that inspired him to pursue legislative office—particularly the issues of how we treat mental illness and substance use, as well as the importance of access to counsel. These have become some of his signature issues in Congress.”

Kennedy may win his primary race, and claim his ancestral Senate seat. He has outraised or outlasted his opponents (a second challenger bowed out of the race this month), and Massachusetts voters, particularly Democrats, have a sort of reflexive affection for his family. It is heartening to see him use the rhetoric of criminal legal reform in his campaign, but if he is going to appropriate reform language, he must account for his actions and decisions working for one of the most regressive DAs in Massachusetts who opposed the very changes he now champions.

Will Isenberg is a public defender in Boston and a partner at Isenberg Groulx LLC. Follow him on Twitter @Wiloceraptor.