Joe Biden’s ‘Crack House’ Crusade

Nearly 20 years ago, Biden urged prosecutors to wield the ‘crack house‘ statute against rave promoters. Now it’s being used to stamp out public health responses to the opioid crisis.

In August 1998, 17-year-old Alabama resident Jillian Kirkland collapsed and later died after a night of partying at the State Palace Theater in New Orleans. The coroner could not determine what drug she overdosed from, but law enforcement, politicians, and the media blamed MDMA, better known as Ecstasy.

Politicians and prosecutors then turned their focus on the rave promoter behind the party on that August night: James D. Estopinal a.k.a. “Disco Donnie.”

In the months following Jillian’s death, two mustachioed DEA agents sporting mirrored aviator sunglasses banged on the door of Estopinal’s New Orleans apartment. “For like 30 minutes they told me what a bad person I was, how I was ruining people’s lives, that what I was doing was a bad thing,” Estopinal told The Appeal. “Then, they offered me a job. They wanted me to finger who the drug dealers were, and I told them that I didn’t know. They asked me how much money I was making a year, and told me they would double my pay [if I cooperated].” Estopinal refused to cooperate and the agents ended the visit but left business cards as a reminder of their offer.

In January 2001, Estopinal became the first rave promoter ever indicted under the federal “crack house” statute, a provision of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 stipulating that anyone who owned, leased, or rented a property “for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing or using any controlled substance” could be criminally prosecuted.

The legislation was authored by then U.S. Senator Joe Biden of Delaware, who by the early 2000s had become an enthusiastic proponent of using the crack-era law against rave promoters like Estopinal. “If I were governor of my state or mayor of my town, I would be passing new ordinances relating to stiff criminal penalties for anyone who held a rave,” Biden said during a March 2001 Senate hearing. “The promoter, the guy who owned the building, I’d put the son of a gun in jail! … Arrest the promoter. Find a rationale unrelated to drugs.”

Nearly 20 years later, Biden is back and leading the pack of more than 20 Democratic candidates for president. The crack house statute returned, too: It’s being used by federal prosecutors in Philadelphia to prevent the opening of the nation’s first supervised injection site where people with substance use disorder can use drugs under medical supervision.

In 1986, homicide rates soared nationally—there were 1,309 murders in New York City in the first 10 months alone—a body count fueled in part by the crack cocaine trade. In August that year, Lawton Chiles, a Democratic U.S. senator from Florida, introduced the Emergency Crack Control Act of 1986, which was folded into Biden’s more expansive Anti-Drug Abuse Act. “[We] are proposing new criminal offenses with stiff penalties for … opening or maintaining a building, or ‘crack house,’ where the drug is produced, sold and used,” Biden said.

More than one decade later, Ecstasy replaced crack as the drug in the crosshairs of prosecutors and lawmakers. This time, the concern was not homicides—which were in steep decline in the late 1990s—but an increase in drug use. From the early 1990s to the early 2000s, the prevalence of Ecstasy use among adolescents doubled. When Estopinal was indicted in 2001 for “knowingly and intentionally” making a building available “for the purpose of unlawfully distributing and using” Ecstasy, U.S. Attorney Eddie Jordan said: “In my time as a prosecutor, this is one of the most unconscionable drug violations I have seen. They used these raves to exploit young people by designing them for pervasive drug abuse.”

Though he was visited by DEA agents years earlier, Estopinal said he was shocked to have the crack house law used against him. “The law is so Orwellian,” he said. “It’s basically a thought crime: If you have knowledge of someone else breaking the law, you can be charged with it. When people smoke weed at Snoop Dogg concerts, I don’t blame the promoter for that.”

As chairperson of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Biden believed otherwise. “I’m the guy who authored the crack house legislation,” Biden said during a March 2001 hearing. “We can use the crack house legislation to tear down these buildings!” Biden said, referring to warehouse parties and underground raves.

Even after federal charges against Estopinal were dismissed in March 2001, Biden did not give up on his quest to use the crack house statute to prosecute rave promoters. In June 2002, Biden introduced the RAVE Act (Reducing Americans’ Vulnerability to Ecstasy), which proposed expanding the crack house statute to more explicitly target concert and rave promoters by including those who hold short-term leases, one-time events, or events in outdoor venues. It proposed that violators would be subject to a civil penalty of $250,000 or twice the gross receipts derived from each violation. “Raves have become little more than a way to exploit American youth,” Biden wrote in the legislation. In the bill, Biden also described bottled water as drug paraphernalia: “many rave promoters facilitate and profit from flagrant drug use at rave parties or events by selling over-priced bottles of water.”

The legislation never came to a vote after multiple co-sponsors withdrew their support. But in April 2003, Biden introduced a slightly different version of the RAVE Act, called the Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act, as an amendment to an unrelated package of child abduction legislation called the Amber Alert bill.

“When Biden couldn’t get the RAVE Act through regular order, he just put it in the Amber bill,” Michael Collins, director of national affairs for the Drug Policy Alliance, told The Appeal. “Now, we’re stuck in this situation where promoters could get prosecuted for selling bottles of water. Chill out tents and drug checking are also forbidden because people have been prosecuted under Biden’s law. This is really endangering people’s lives.”

Biden’s championing of a broad application of the crack house statute has had an effect on drug policy far beyond raves. In February, William McSwain, the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, sued Safehouse, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit that is planning to open America’s first officially sanctioned supervised injection site. In his civil complaint against Safehouse, McSwain argued that its proprietors would be in violation of Biden’s crack house law. Attorneys for Safehouse countered that the statute was never meant to target medical or health establishments, and that as a nonprofit, Safehouse would not benefit from supervising drug use.

“We know right now that it is permissible to provide injection equipment, it is permissible to provide fentanyl test strips, it is permissible, in fact, encouraged, to save lives with naloxone,” Ronda Goldfein, an attorney representing Safehouse, told The Appeal. “Our purpose is to save lives in between those permissible activities. What we would like to do does not violate the actual letter of the law nor the spirit of the law.”

Goldfein also noted that as a nonprofit, Safehouse would not benefit from people’s drug use. “If I own a crack house, I don’t want you to stop using drugs. I want you to continue to use drugs every single day. We’re successful at Safehouse if we both save a person’s life and get them into treatment, which is not what you’re intending if you operate a crack house.”

In an Aug. 19 evidentiary hearing, McSwain asked a series of questions about the sale or administering of drugs to Safehouse president Jose Benitez—all of which received a curt “no”—that demonstrated just how committed prosecutors were to the idea that a safe injection site would be similar to a crack house. That day, former Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell fumed that law enforcement opposition to safe injection sites would mean more needless deaths. “Over the last two years, more than 2,300 mostly young people have died of overdoses—that’s four times the homicide rate in Philadelphia,” he said. “The system is not working.”

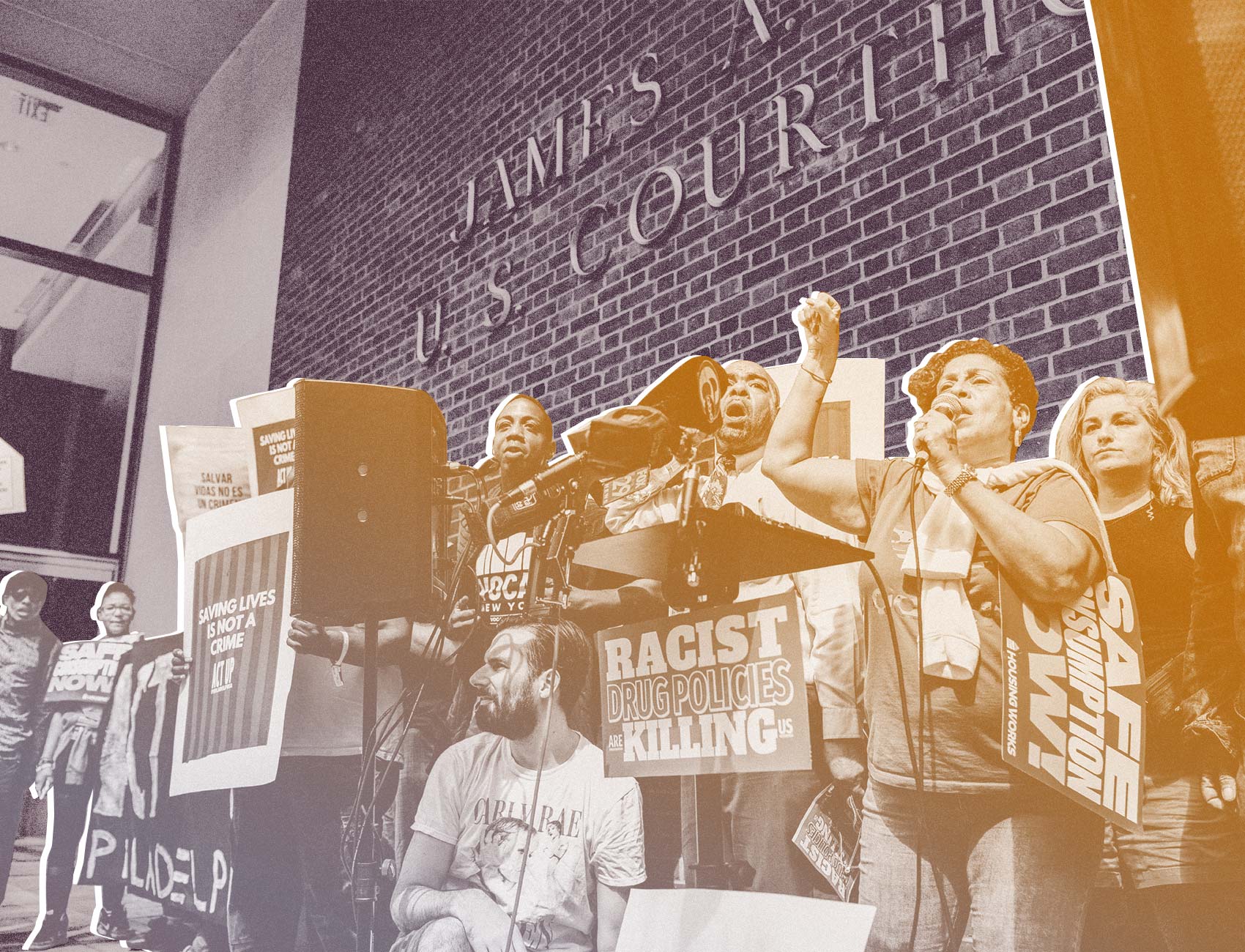

On Sept. 5, Safehouse supporters rallied outside a federal courthouse in Philadelphia where U.S. District Judge Gerald A. McHugh heard arguments about whether the crack house statute prohibits a supervised injection site. “The issue before me is not whether this is good public policy,” Judge McHugh said. “The issue before me is the application of the statute.”

McSwain argued that “the statute is clear. Congress has made a judgment—don’t set up a place to do drugs.”

Judge McHugh repeatedly asked McSwain whether the framers of the statute had supervised injection sites in mind when they wrote it. McSwain responded by saying that “there are some statements from Senator Biden … that don’t specifically talk about injection sites but the language and the logic of the statements would apply to injection sites.”

McSwain then quoted comments Biden made when he attempted to pass the RAVE Act in 2003. “In the 2003 amendment, Senator Biden said, ‘The bill targets any venue whose purpose is to engage in illegal narcotics activity,’” McSwain said. “[Biden] talks about, ‘My bill would help in the prosecution of rogue promoters who not only know there is drug use at their event, but also hold the event for the purpose of illegal drug use.’”

The Biden campaign did not respond to multiple requests from The Appeal for comment.

Collins says that Biden’s crusade to widen the application of the crack house statute is a legacy that he must own. “This is different from the 1994 crime bill, where a lot of politicians have their fingers dirtied for that,” Collins said. “The Rave Act is pure Biden, from start to finish.”