“They took my life away for nothing.”

James Carver spent 36 years in prison after he was convicted of setting one of the deadliest fires in Massachusetts history. But after reviewing new scientific evidence, a judge set him free.

This piece was published in collaboration with the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism.

It was the early morning of July 4, 1984. A Beverly police officer was driving down Rantoul Street when he heard the owner of the Sunray Bakery screaming to get his attention. The officer turned his cruiser around, then came to a stop. The owner pointed to a rooming house a few blocks away.

It was burning.

The inferno killed 15 people, making it one of the deadliest fires in Massachusetts history. Eventually, a young man would be convicted of setting the blaze and sentenced to spend two consecutive lifetimes in prison for what The Beverly Times described as the “worst mass murder in Massachusetts history.”

But that man, James “Jimmy” Carver, insisted on his innocence. And after Carver’s lawyers presented new scientific evidence at a hearing last spring, a judge agreed that he was entitled to a new trial. In December, the judge ruled that the trial prosecutor relied on junk science to show the fire was arson and unreliable eyewitness testimony to place Carver at the scene. In February, the judge vacated Carver’s sentences and released him without bail—finally freeing him after more than 36 years of incarceration.

At 4:18 on that July 1984 morning, the Beverly patrolman radioed the police station to say he was investigating a fire in progress. He then raced a half-mile to the source: the Elliott Chambers Rooming House. The three-story building, located at the corner of Rantoul and Elliott Streets, had commercial space on the first floor, while residents lived on the upper two levels.

When the officer arrived, he saw “flames shooting out from the front entrance” and “billowing straight up to the second and third floors,” according to his report.

Firefighters showed up moments later and began a grueling effort to rescue trapped residents and extinguish the blaze. Before firefighters began applying water, they used ladders to save nine people, some hanging from windows. A few people jumped instead of waiting for help. Others went deeper into the burning building instead of remaining at the windows, and The Beverly Times later wrote that “several firefighters were nearly sobbing with frustration” when they could not save them.

Despite the efforts of first responders, 14 people died that morning, most from burns or smoke inhalation. Officials said the fire tore through the old wood-frame building so quickly that responders found six of the deceased victims in their beds. One man jumped from a third-story window, hit a traffic-control box, landed on the pavement right in front of the officer who called in the fire, and was pronounced dead on arrival at a local hospital. A fifteenth victim passed away from respiratory failure a month later.

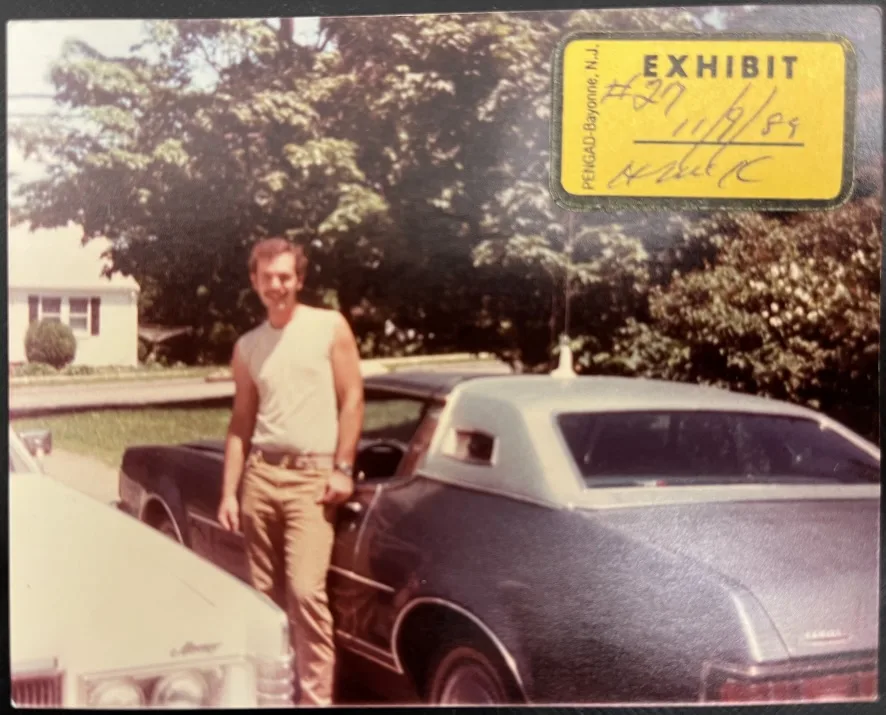

A day after the blaze, state and local officials told the media that they believed it was a case of arson. Within days, an anonymous tip led the Beverly and Massachusetts State Police to focus on Carver, a 20-year-old who lived with his family in Danvers and worked for a taxi company and a pizza place in Beverly.

However, it would be nearly four years before an Essex County prosecutor obtained indictments against Carver for arson and 15 counts of second-degree murder. When police arrested Carver in May 1988, he was 24 years old, working as a truck driver, and had moved to Ipswich. He was also just starting a family. He lived with his then-wife, who had given birth to the couple’s daughter about seven weeks prior.

When the case went to trial in 1989, the prosecutor alleged that Carver caused the inferno by pouring a flammable liquid on a bundle of newspapers and burning it outside the Elliott Chambers’ door. The prosecutor said that Carver set the fire because he was angry his ex-fiancee had dated a man who lived in the rooming house. However, Carver’s parents testified that he had been sleeping at home in Danvers when the fire started.

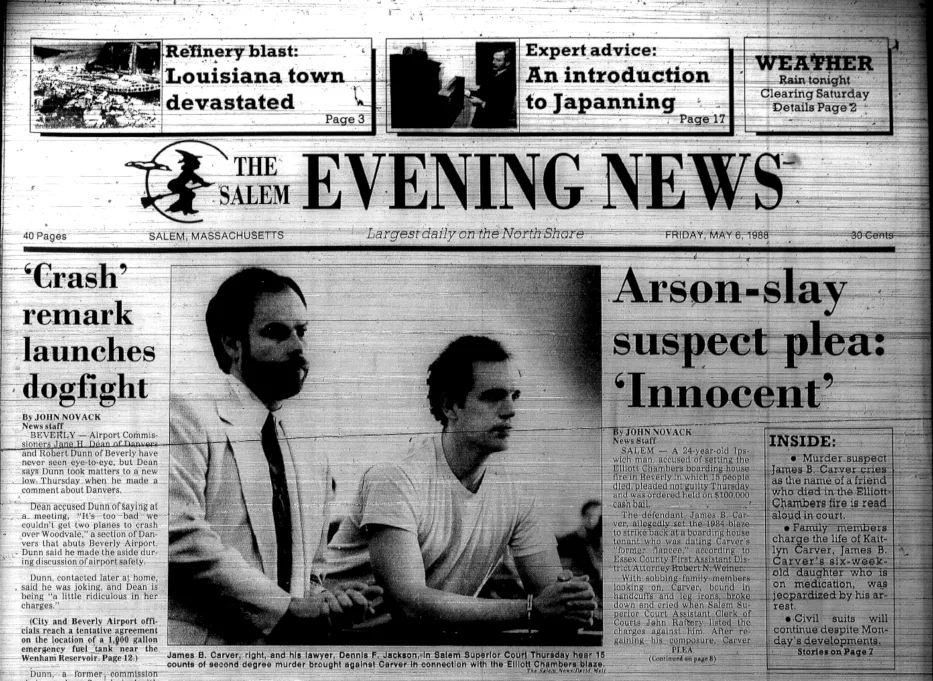

After three weeks of testimony, the presiding judge declared a mistrial when it came to light that the prosecutor withheld reports showing a witness had made contradictory statements to police. Later in 1989, the prosecutor tried Carver a second time before a different judge and jury—and secured a conviction. According to The Salem Evening News, Carver’s wife screamed as the verdicts were read.

“No, no, no, no,” she wailed. “He didn’t do it.”

She pounded her fist on a railing and was removed from the room by court officers. Carver broke down and cried after hearing the final “guilty.”

Now 61, Carver has difficulty standing, requires a wheelchair to get around, and is incontinent due to a 2005 surgery to remove a brain tumor, according to court records. He also experiences tremors, is deaf in one ear, and struggles to hear with the other. While he was in prison, his mother, father, and older brother passed away. He and his wife divorced in 1991, even though she always believed he was innocent. And he couldn’t see his daughter, except in a visitation room.

“They took my life away for nothing,” Carver said. “I’ve always said that I’m not the person that was involved in [the fire], and I meant it.”

He added: “I believe that if you did something wrong, you plead guilty to it. I believe if you’re innocent, you fight it all the way with everything you’ve got.”

In Massachusetts, a judge “may grant a new trial at any time if it appears that justice may not have been done,” according to the state’s rules of criminal procedure. Lawyers must either present substantial evidence unavailable during the original court case—or show that the defendant’s trial lawyer was unusually ineffective.

In March 2022, Carver’s lawyers filed a motion to overturn his convictions, arguing that new scientific evidence proved his innocence—and that there was no conclusive evidence the Elliott Chambers fire was arson in the first place. It was Carver’s fifth attempt at overturning his convictions, but it was the first attempt by his current legal team. It was also the first attempt to use scientific evidence to challenge the prosecution’s theory about how the fire started. And it succeeded.

In a December ruling, Essex County Superior Court Judge Jeffrey Karp threw out Carver’s convictions. According to the judge, a now-deceased fire investigator falsely testified at trial that there was physical evidence someone started the blaze with a flammable liquid like gasoline. No such proof existed. Karp said the investigator relied on myths about fire that have since been discredited.

The investigator, a deputy chief fire marshal for Nassau County in New York, was brought in to assist state and local officials in Beverly. The investigator was sent as part of a federal program run by what was then called the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. The investigator testified that the fire was deliberately set on a bundle of newspapers that a firefighter found in the alcove that contained the rooming house’s entrance.

The investigator said the blaze must have started at ground level, where the newspapers were discovered. He said this location was the lowest point of burn and claimed that flames can’t spread downward. He also testified that “alligator charring” marks and “swirling smoke” stains left by the fire proved that it was started using a flammable liquid—even though lab tests did not detect traces of any such substance on the newspapers or in the alcove.

But at a hearing in April, these crucial claims were debunked by Craig Beyler, a retired fire-safety engineer who reviewed the case for Carver’s legal team.

Beyler said the investigator’s testimony about “alligator charring” and “swirling smoke” was based on ‘80s-era myths scientists have since rejected. He added that the fact that the lab tests were all negative meant that the investigator’s conclusion was “mere speculation.” And the idea that fire cannot travel downward, he explained, was also false.

Beyler said investigators failed to collect enough evidence to rule out electrical causes. He said the blaze’s cause could not be determined. However, he said that scientific testing has shown it would have been impossible for the newspapers to have generated a flame powerful enough to have spread to the building.

Beyler said the fire did not start at ground level, but instead began in the overhang of the alcove where the newspapers were found. The damage to the alcove’s walls was limited. But the fire had so significantly damaged the overhang that pieces of the ceiling were missing. He said the damage to the walls and newspapers could have been caused by “drop-down burning,” which is when flaming debris falls from a higher level of a structure to a lower one.

Karp determined that Beyler’s new testimony was credible and ruled that it was significant enough to warrant granting Carver a new trial.

Karp also focused on testimony by a cab driver who claimed he saw Carver outside the rooming house shortly before the fire. The judge said the witness was not reliable, citing April 2024 testimony by retired Stony Brook University psychology professor Nancy Franklin, an eyewitness-memory expert who reviewed the case for Carver’s legal team.

In her testimony, Franklin said that it’s common for people to make mistakes when trying to identify strangers. She explained that misidentifications occur both because of the limitations of human memory and because distinguishing the unique characteristics of one stranger’s face from another is inherently challenging. She said identification procedures conducted even one week after an incident are extremely unreliable. Law enforcement did not show the cab driver a photo array with Carver’s picture for seven weeks.

Investigators then showed the witness the same array two more times before showing him an in-person lineup. Franklin said the repeated identification procedures were problematic because of what researchers call the “mugshot-exposure effect”: When witnesses are shown the same person’s face multiple times, they develop a sense of familiarity that can cause them to confidently, but incorrectly, select that person.

Most strikingly, the cab driver had picked Carver from the photo array after first selecting someone else who was not a suspect. Franklin said this was a tell-tale sign the witness’s testimony was unreliable.

Karp wrote that if the case were tried today, Carver would be able to present an expert witness like Franklin, who could inform the jury about the now-accepted problems with eyewitness testimony and the specific issues with the cab driver’s account.

Essex County District Attorney Paul Tucker wrote in a statement that his office “strongly opposed Carver’s release” and is appealing the ruling that overturned the convictions. The district attorney’s office can also try Carver a third time, but Tucker declined to say whether prosecutors would do so if they lose the appeal.

“Any wrongful conviction claim is taken very seriously and is extensively reviewed by our Appeals Division and senior members of the Superior Court Trial Team,” Tucker said. “The district attorney is committed to upholding the highest ethical and moral standards for all prosecutions. In this case, we respectfully disagree with the judge’s ruling and have appealed. Our decision reflects our analysis of the strength of the case against the defendant, including his motive, threats, and multiple admissions to having committed the crime.”

Robert Weiner, the now-retired assistant district attorney who prosecuted the case in 1989, answered his phone the day after Carver was released. After this reporter introduced himself, Weiner immediately ended the call without saying anything. He did not respond to a subsequent voicemail message.

Carver said the hardest thing he endured while in prison was losing his family. He said he still loves his ex-wife, Maryjane Dempsey.

“To have her ripped away, torn away, was hard,” he said. “Because she was really a true love. […] And I believe if this case didn’t happen, that I would still be married to her today.” However, he said, “I’m not going to take Maryjane away from her boyfriend. I made sure I told him that. […] [I] told him thank you for taking care of her and loving her.”

Carver’s parents supported him throughout his two trials and incarceration. They spent around $200,000 on legal fees and private investigators, which led to them losing their Danvers home to foreclosure in 1992, according to news reports. Carver’s mother, who died in 2002, was the first one to pass away.

“My mother was really sudden,” he said. “She had a stroke, and she was just gone. […] That was my first big blow in prison. I thought that I had been really knocked down hard. And then when I got to go see her at the funeral home, I just kept telling her to wake up, […] and I realized it’s just not going to happen.”

Carver’s father died in 2022, several months after Carver’s lawyers filed the motion that eventually overturned his conviction. “My father told me when he was at the hospice center that he tried to stay alive to see me come home, and that was kind of hard to take,” Carver recalled.

While his father was dying, Carver said, the Massachusetts Department of Correction denied his emergency furlough request. He wasn’t able to visit the hospice facility and see his father in person.

“When I was on a Zoom visit with him after he had a stroke, I actually watched him pass away,” Carver said. “Watching him pass away like that, I’ll never forget it.”

He said the DOC also denied his request to attend his father’s wake or funeral. “I couldn’t understand why I was allowed to leave a maximum-security prison to go see my mother, but now I’m in a medium-security prison and I was denied to go see my father,” he said.

Carver’s older brother, Bruce, died in June. “That was hard,” Carver said. “I’ve lost three family members since being locked up.”

Carver said that in December, when his lawyers told him that his convictions had been overturned, he thought about his deceased loved ones.

“I went back to my cell and just took a deep breath and then just broke down, just let the tears come up,” he said. “And I talked to my mom, and talked to my dad, talked to my older brother, and I talked to God and thanked him.”

The cemetery was the first place Carver wanted to go once he was released.

Carver’s attorneys, Lisa Kavanaugh and Charlotte Whitmore, focus on exonerating innocent people whose lives have been turned upside down by the criminal legal system. Kavanaugh directs the Innocence Program at the state’s public defender agency, the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS). Whitmore is a staff attorney at the Boston College Innocence Program.

After Carver’s convictions were overturned, Kavanaugh and Whitmore provided a proposed release plan to the court before a Feb. 4 bail hearing. According to those documents, Carver was accepted into a residential-care home, a type of assisted-living facility that lacks 24-hour nursing staff but can accommodate his disabilities and medical issues. Carver is largely independent, but he needs help managing his medications and preparing meals due to his decades of incarceration.

About 30 supporters showed up for the bail hearing at the Superior Court building in Lawrence. Among them was Carver’s younger brother, Bill, who flew in from Michigan the day before. James Carver’s ex-wife, Dempsey, attended the hearing with her boyfriend and sister. Carver and Dempsey’s daughter, Kaitlyn Verzi, attended with her husband and the eldest of their three sons.

Verzi, an emergency-room technician who lives in New Hampshire, addressed the judge in a letter before the hearing.

“I was born very prematurely and was a sick baby for a long time, so my father’s only memories of being with me […] [were] of me being hooked up to ventilators, heart monitors, and being nearly untouchable in an incubator,” Carver’s daughter wrote. “My parents had just brought me home from Mass General Hospital and were out getting my medication to keep my heart going [when he was arrested].”

When Verzi was a child, she and her grandparents visited her father in prison every week, according to her letter.

“Having to take my little shoes off, walk through metal detectors, be searched, and walk through giant scary steel doors. As a child this was normal to me,” she wrote. Verzi said she continued visiting her father regularly until 2017, only reducing the frequency of her visits because the prison’s policies made it difficult to bring her children.

Carver said he always told his daughter that he would get out of prison someday, but the separation tore at him.

“That’s pretty tough to have your child want you to come out at that moment, and […] all you can do is just hold on to her and tell her you love her,” he said. “And my parents, my mother and father, [were] the same way, because I love them and they [would] walk out in tears a lot of times. And that’s hard to see.”

At the Feb. 4 hearing, Asst. District Attorney James Gubitose asked Judge Karp to hold Carver without bail—a request that, if granted, likely would have led to Carver spending at least another year in prison while the appeal stretched on. Gubitose argued that Carver is a flight risk despite his disabilities and medical issues.

“Some of the support that the defendant does have […] are very close family members who are adamant that the defendant is innocent,” Gubitose said. “And I would suggest to you that they have an incentive to assist the defendant not to go back to jail.”

Kavanaugh said Carver has no reason to flee—and his family members have no reason to help him escape.

“This is the moment of hope that they have been waiting for for decades, and they are here because they fully stand behind him and they want him to see this process through to its conclusion,” Kavanaugh said.

Karp took a short recess to consider the request. When the judge returned, he said he was releasing Carver.

Kavanaugh and Whitmore immediately turned to face Carver and smiled. Kavanaugh placed her hand on Carver’s back. Carver stared straight ahead for a moment, quivering slightly, and pressed his lips together. He looked over at Kavanaugh, who nodded at him. He turned his head forward and took a breath. Not long after, tears filled his eyes.

Verzi smiled, and her husband took her left hand. Seated behind them, Carver’s ex-wife, Dempsey, looked down in shock, covering her mouth as her boyfriend held her. Dempsey looked up at her daughter, who smiled back. Verzi reached her free arm behind her and held hands with her mother, who began taking deep breaths. Bill Carver’s eyes began to well up. He took a sip of water, removed his glasses, and wiped away his tears at almost the exact moment as his brother.

“I was so happy,” James Carver later said. “I was hurt because of what the system has done to me. So I’m happy and hurt at the same time. I was always told to believe in the system and everything. But finally, a judge listened.”

Prosecutors have argued that, despite the flaws in their case, there is still sufficient evidence of Carver’s guilt, including testimony from witnesses who said that he threatened one of the victims the night before the fire and that he made incriminating statements afterward.

However, according to Karp’s ruling, some of these witnesses had credibility issues. Moreover, a jury would be more likely to doubt their testimony now that the new scientific evidence would give them reason to question whether someone deliberately set the fire, the judge wrote.

The star witness at the two 1989 trials testified that she was Carver’s former friend, and that he tearfully confessed after inviting her to his home in October 1984. According to the witness, Carver said he had wanted to scare his ex-fiancée and the man she had been dating, so he set a fire by pouring gasoline on newspapers and igniting them with a match. The witness said Carver never specified what fire he was talking about. But she believed his comments to be about the Elliott Chambers.

The witness acknowledged that she didn’t tell police about the alleged confession until investigators called her in March 1987, after she had moved to New York.

After Carver was arrested in 1988, Kevin Burke, who was the Essex County district attorney at the time, said that the witness’s statement to police was what finally made it possible for his office to file charges.

“It was the kind of statement that allowed us to put together all the other corroborative evidence and fit the pieces of the case together,” Burke said at a press conference, according to The Salem Evening News.

Karp’s ruling notes that the “credibility and the accuracy of [the witness’s] memory suffered from her two-year delay in disclosing the admission to the police and the absence of evidence that any of the several people she told about the admission shortly after hearing it, including a Beverly firefighter, considered it serious enough to report to the authorities.”

Karp also wrote that there was a lack of reliable physical evidence tying Carver to the fire or placing him at the scene. However, the judge noted, there was information that contradicted the prosecution’s theory, including the testimony by Carver’s parents that he was sleeping when the fire started.

“At bottom, the evidence against Carver was ‘far from overwhelming,’” Karp wrote.

The Elliott Chambers building is no more. A CVS now resides at the site it once occupied. But a reminder of the tragedy’s terrible cost rests at the corner of the street. A modest hunk of polished granite sits between two benches; affixed to it is a bronze plaque engraved with the names and ages of the 15 people killed by the fire. The Elliott Chambers Fire Memorial Foundation donated the monument in 2010.

The 15 victims left behind many grieving family members. Tracie Lee Dalton was the only one of them who attended Carver’s bail hearing in person. Dalton’s older brother, George Flynn, died in the blaze at age 18.

Dalton said her brother was a “loner” who had few friends but enjoyed spending time with family. She said Flynn liked to draw, build models of ships and cars, and was interested in electronics. Shortly before the fire, she said, Flynn graduated from Beverly High School and moved to the Elliott Chambers because it was near their grandparents’ home and his job at an electronics company.

At the hearing, Dalton sat with her husband and a victim advocate from the district attorney’s office. Dalton showed little emotion, but she said in an interview that she believes Carver is guilty and was angry that he was released. She said she read Karp’s December ruling and disagrees with it.

“He doesn’t think that the fire investigators at the time did what they were supposed to do,” she said. “But you’re only supposed to get a bite at the apple once. If you’re convicted, you’re convicted.”

Dalton said that before the hearing, she briefly met with prosecutors, who told her it was likely Carver would be released.

“I was upset—because my brother doesn’t get […] a bail hearing,” she said. “The bail hearing was a little one-sided. It was all about [Carver] and not his victims.”

Dalton said she and Flynn knew Carver and his younger brother, Bill, from participating in a drum and bugle corps when they were kids. Carver said he was friends with Flynn and went to his funeral.

“I feel bad that that happened to people’s families, and their families were torn apart in such a horrible way,” Carver said. However, he said he wants the family members to understand that he is not responsible. “I wish the people that are hating me right now could meet with me someday and know the person that I am—that I never, ever would hurt anybody whatsoever.”

He also said that two now-deceased survivors, both of whom were called as witnesses by the defense during his second trial, believed he was innocent and wrote to him in prison. He said he has often thought about and prayed for them.

“I can only imagine how awful it must have been to lose family in that fire,” Kavanaugh said. “I think that there ought to be more resources available to help people understand why a conviction is overturned. […] But I can’t blame them for feeling invested in the original trial verdict, and we certainly feel great empathy for them for their losses.”

Although Dalton was the only victim’s relative who attended the hearing in person, others listened to it using a phone line the district attorney’s office requested.

One of them, Julie Nickerson Benedix, lost three people to the fire—her brothers, Rick and Ralph Nickerson, and her grandmother, Hattie Whary, who managed the rooming house.

“They were buried on my fifteenth birthday,” Benedix said. “Since I was 14, I’ve never had a birthday.”

Benedix’s older brother, Rick Nickerson, was the victim whom prosecutors allege Carver threatened the night before the fire. That night, the two young men spoke outside the pizza place where Carver worked and the neighboring pool hall that employed Nickerson. Three witnesses testified that they heard Carver threaten Nickerson for dating his ex, but they all gave different accounts of what he said. Two of the witnesses did not tell police about the alleged threat until years after the fire.

According to one of the witnesses, Nickerson was on a date with a different young woman the night before the fire. The woman, who did not testify, told investigators she was present when Carver allegedly made the threat but did not hear what he said, according to police records. She also said that Nickerson never mentioned it to her.

In 2004, Carver told The Salem News he didn’t know Nickerson lived at the Elliott Chambers. The only evidence to the contrary was testimony from the former friend who alleged that Carver confessed. The witness testified that Carver said he followed his ex and Nickerson home before setting the fire, but did not specify whose home it was or where it was located. However, Carver’s ex testified that she wasn’t with Nickerson then and didn’t know where he lived.

Benedix said Rick Nickerson liked rock music, played the guitar, and joined the US Army after graduating from high school in Maine. He eventually moved to Beverly, where he got a job and lived at the rooming house with their grandmother. He was 21 when he died.

Nine-year-old Ralph Nickerson was the youngest victim. He lived with his parents in Maine but was visiting his grandmother and brother at the time.

“[Ralph] had a lot of friends,” Benedix said. “A lot of the friends actually came to the funeral, which in itself was heartbreaking. […] To see that many kids at the funeral was just awful.”

Benedix said she takes medication for depression, anxiety, and PTSD related to the deaths of her loved ones. She was also angry that Carver was released. She said she listened to the hearing alone at her home in Maine. Afterward, she said, she spoke on the phone with the victim advocate and cried.

“I was flabbergasted,” Benedix said. “I’m thinking there is no way they are letting him out. There’s no way. And they did. […] For all this time, we felt a little at ease knowing that the person that lit a match and killed all these people was behind bars and had no chance of getting out.”

As soon as the February bail hearing ended, Carver addressed one of the court officers.

“Can I hug my grandson now?” he asked.

It was something Carver had been unable to do since the now-12-year-old boy was a toddler. However, the officers told Carver he would have to wait a few more moments. They then ordered everyone but Carver and his lawyers to leave the room.

Verzi and her mother hugged before exiting. Bill Carver continued to cry as he stood outside the doorway. Asked how he was feeling, he struggled to respond.

“Speechless,” he said, his voice cracking. “Thirty-eight years I’ve been waiting for this.”

Verzi stood beside her uncle.

“I feel numb right now,” she said. “Like it hasn’t hit me.”

Inside the courtroom, James Carver thanked his lawyers. Kavanaugh stayed with him while a court officer escorted him to the basement level, removed his handcuffs and ankle cuffs, and brought him to the probation office to sign paperwork and strap on a GPS ankle monitor, an ever-present reminder that prosecutors are trying to put him back in prison.

Whitmore brought Carver’s family to the basement, where they met him outside the probation office and formed what Kavanaugh called a “hug line.” Carver’s daughter was the first one in the queue.

“That was the first moment that I was able to see him as a free man,” Verzi said. “I was able to go up to him without guards telling me I can’t hug him or anything. […] I said, I wish Grampy was here. And he said, Me too. And he started to cry.”

After that, Carver hugged the rest of his family and his lawyers. “To be able to hold [my grandson] when I was uncuffed was big,” Carver said. “He didn’t want to let go. Neither did I.”

At 3:58 PM, Carver emerged from the elevator on the first floor. His lawyers and relatives joined him, with his daughter pushing his wheelchair. Now wearing a gray hooded sweatshirt with the logo for the CPCS Innocence Program, he smiled. The other supporters, who had lined up in the hallway, clapped for him. He kissed one of them on the cheek, shook hands with others, and shared a long hug with his ex-wife, Dempsey. And then Verzi wheeled her father through the doorway to freedom.

“It’s something that we’ve only ever talked about, and to actually be living it was just an unreal experience,” she later said. “I can’t even put words with it, honestly.”

“No more handcuffs,” Kavanaugh said as Verzi wheeled her father down the ramp outside.

At the bottom of the ramp, Dempsey approached and hugged Carver again.

“Oh my God, I cannot believe he’s out,” she shouted during the embrace. “He’s free.”

She held Carver’s hands and looked him in the eye.

“You are free.”

After Carver left the courthouse, he was assisted into Bill’s rental car, and the brothers set off to Danvers to look at their childhood home before heading to the residential-care home. On the way to Danvers, Carver wanted to stop for coffee—a large regular with Sweet’N Low from Dunkin’.

“He is a true New Englander,” Bill said. “Although he was shocked at the price of it.”

The following day, Verzi and her husband brought their three children to the residential-care home to see their grandfather. Bill drove separately.

The visit was the first time Carver had ever seen his two younger grandsons, now ages seven and nine, in person.

“That was beautiful,” he said. “I’ve always maintained a relationship with [my grandsons] through video calls and stuff like that. […] But to have them all together at the rest home when they came to visit me and be able to hold them—oh my God, it was just—I can’t even describe the feeling.”

Carver’s family brought him to a Target to buy him clothing and other essential items. Once again, he was caught off guard by the prices. Verzi said she asked her father whether he wanted a steel mug to keep next to his bed, and he was shocked when she showed him one that cost $25.

“He was just looking around like, Wow,” Verzi said. “He hadn’t experienced seeing a store that big.”

After the Target trip, Carver asked his family where they were going next. To his surprise, Verzi told him they were going to the cemetery in Marblehead where his parents and older brother were buried. “He started to choke up and get teary-eyed,” Verzi said.

That frigid February day, Carver sat in his wheelchair looking at the three graves for the first time. He greeted his deceased family members, telling them that he loved them—and that he was finally home.

“The cemetery was peaceful,” he said. “And I know that they were in God’s hands.”

Carver said the most challenging part of transitioning to freedom was “overcoming fear of being on my own.”

“It’s like a cat coming into a new house,” he explained. “It’s testing out the areas, trying to figure out what’s going on. And that’s what I’m trying to do. […] I just can’t believe how so much has changed. I’ve never held a cell phone in my hand in my life, right? Now I’ve got a cell phone, and it’s crazy the way it works and how fast it works.”

Almost a week passed before Carver left the residential-care home by himself. He wheeled himself down a hill while on the way to a CVS to get medication and worried that he wouldn’t be able to get back up. Once he got to the store, he felt disoriented.

“I’m looking at stuff on shelves, but I’m not seeing the stuff, if you know what I mean,” he said. “And finally, I just had to ask somebody what aisle [it was] in, and I got it.”

He had a similar experience the first time he took a bus to a medical appointment by himself. “I was in a hospital that I knew,” he said. “But now I’m frozen. I’m like, Okay, am I doing this right?” He said he got lost, his appointment ran late, and he missed the bus and had to get a taxi voucher to get home.

Reflecting on his first few weeks of freedom, Carver said that moving into the residential-care home was challenging but has been getting easier.

He said he’s befriended two cats living at the home. They’ve helped alleviate his anxiety. On her second visit to see her father in his new home, Verzi brought him some cat treats.

“I’m constantly giving them treats,” Carver said. “They’re sleeping in the bed with me, [or] one’s in the wheelchair and one’s in the bed. And now I can’t get rid of them. I don’t want to get rid of them.”

Carver said he’s taking life day by day now. His long-term goal is to spend time with his family outside of Massachusetts after his case is resolved and he’s no longer prohibited from leaving the state.

“At some point, I want to be up in New Hampshire and with my family,” he said. “And I’d love to be able to go out and see my brother [Bill in Michigan], go to the Henry Ford Museum, things that he showed me on the phone, […] and spend some time with him.”

Andrew Quemere is an independent investigative journalist from Massachusetts. He writes about issues like wrongful convictions, police misconduct, and government transparency. He is the author of The Mass Dump newsletter.