‘It Will Certainly Save Lives’: A Q&A About Medicaid Coverage For People Preparing For Re-entry

Federal policy denies incarcerated people Medicaid coverage, making re-entry a time of heightened health risks. Tracie Gardner of the Legal Action Center explains New York State’s effort to “break the cycle of justice-involvement, poor health, economic instability, and recidivism that plagues individuals and families throughout New York.”

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal.

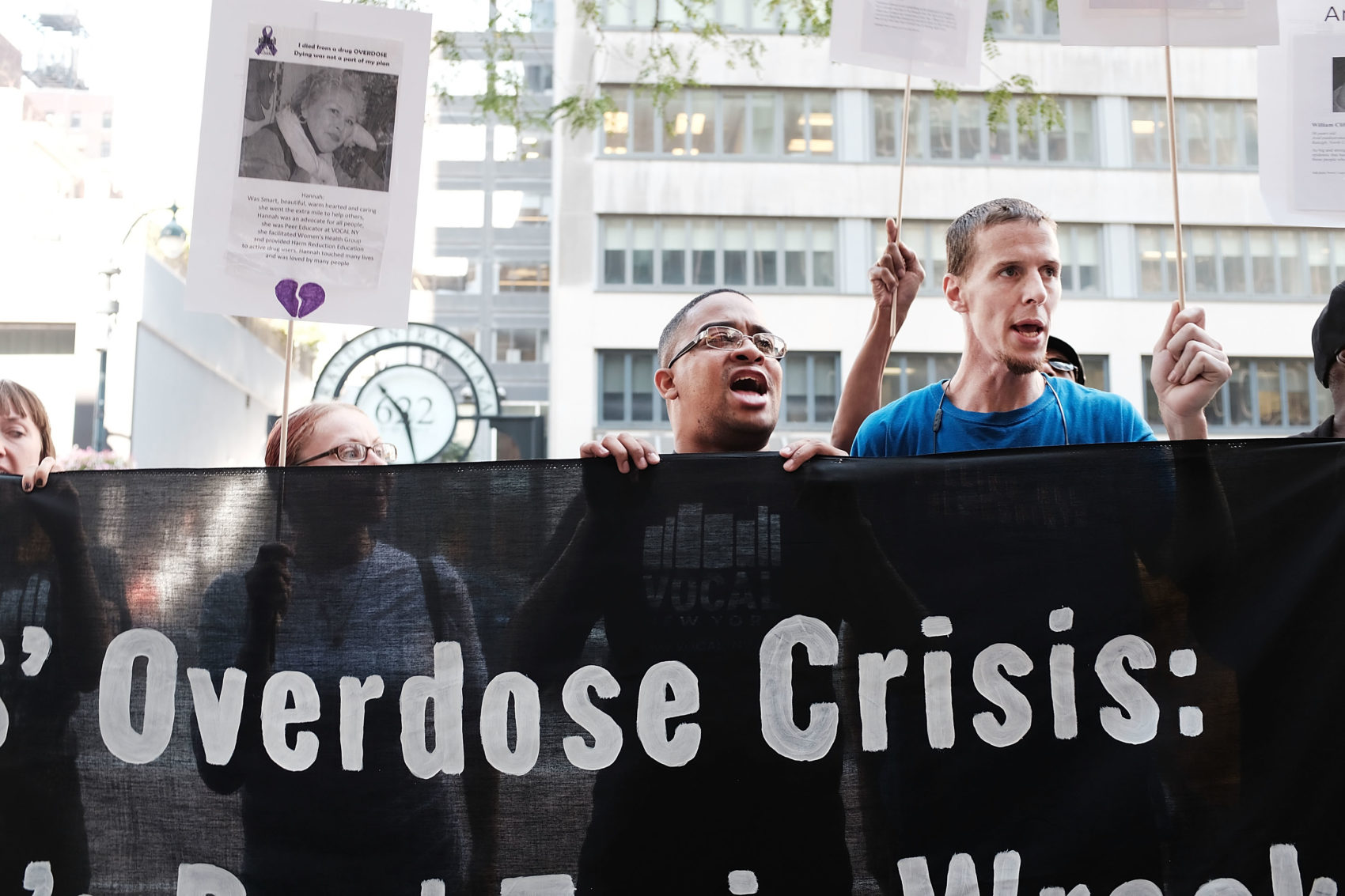

People who are sent to prison and jail in this country have rates of ill health, childhood trauma, mental illness, and substance use that are far higher than the general population. This is not surprising, considering the decades-long erosion in community mental health care, the failure to adequately fund substance use treatment, and the criminalization of mental illness, substance use, and poverty. Incarcerated people are also far more likely to have chronic and communicable diseases. In jails and prisons, medical care is often substandard, sometimes dangerously so. Upon release, health risks are only compounded: A study of people released from prison in Washington State found that the risk of death in the two weeks after release was 12 times higher than that of the general population, largely because of overdoses.

A major contributing factor to the dangers in the period of initial re-entry is the “inmate exclusion policy.” This federal rule forces states to suspend or terminate Medicaid coverage during incarceration. This makes continuity of care, what one expert described as “an essential part of re-entry services [that] can lower the risk of reincarceration,” virtually impossible.

New York State, which has taken modest steps in recent years to increase access to care for people while incarcerated and upon release, now plans to apply for a federal waiver that would allow it to reinstate Medicaid coverage for people who are within 30 days of release from jail or prison. In an opinion piece published yesterday in the Times Union, Tracie Gardner and Shelly Weizman, both former assistant secretaries for mental hygiene for the state, argued for the importance of this proposal.

In an email interview, the Daily Appeal asked Gardner, now vice president of policy advocacy at the Legal Action Center in New York, about New York’s proposal and why it matters. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What prompted New York State’s decision to apply for federal approval for 30-day Medicaid coverage right now?

There was an attempt to apply in 2016, right before the election, to address re-entry and health concerns. That application was rescinded because of the state’s concerns about how it would be handled by the new Trump administration. The state’s decision to reapply is now especially driven by the impact of the overdose epidemic on individuals leaving corrections. It is also nicely timed with an election year.

What is the process now? Do you think the state’s application is likely to be approved?

New York has not yet formally submitted the application. The State Department of Health just closed a public comment period. The state will review and incorporate comments to produce a final draft, which will be submitted to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] for review. CMS will also invite public comment at this stage, and we encourage all impacted stakeholders to make their voices heard in this process. We don’t know exactly when this will occur, but will be following it closely and posting updates on our web page.

Apart from this application, what can New York State do to facilitate coverage before or upon release?

The state is seeking a federal match to its own Medicaid dollars through the waiver amendment application. The state can and has used its own resources to fund care behind bars. County jails are developing capacity to treat individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD). Rikers Island has been providing all three FDA-approved medications to treat OUD for 30 years. These are all work-arounds of the “inmate exclusion” in Medicaid. New York also operates six Medicaid health home pilots with a specific focus on the criminal justice population.

And if it is approved, are there other steps you hope the state will take?

We hope that the state will put rigorous evaluation in place to look at health and criminal justice outcomes while the waiver amendment is operational. We also hope that the state will support the development of a health and support service infrastructure that will be responsive to the needs of individuals who are transitioning back to their communities from incarceration, especially those with HIV, substance use disorder, and/or mental illness.

There are a number of organizations that work with and in correctional facilities to help people with complex and chronic health conditions transition to the community. If the waiver amendment is approved, there will still need to be a great deal of coordination to achieve success. Presumably, services such as care management, medications, and comprehensive assessments would be available in a way that supports healthy re-entry. There are many alternatives to incarceration and re-entry organizations that have longtime expertise and are well-positioned to ensure these services can reduce the likelihood that people are re-arrested or even end up incarcerated in the first place. We are poised to be able to break the cycle of justice-involvement, poor health, economic instability, and recidivism that plagues individuals and families throughout New York.

How would this work for people detained pretrial, whose release dates are not necessarily known 30 days in advance?

We have asked the state to include in its application 15 days of full Medicaid coverage for individuals when they are admitted to jail, since as you note, release dates are often unknown. According to the New York City Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice and DOCCS [Department of Corrections and Community Supervision], the vast majority of jail-based clients typically spend less than two weeks in jail before returning to the community, so this 15-day period would give outside providers a chance to work with folks right away to create connections to community resources.

New York currently ensures that insurance is “turned on” before release. What have the effects of that been?

In 2007, New York became one of the first states to suspend Medicaid coverage for individuals entering incarceration rather than wholly terminating coverage.

In 2017, New York became the first state to begin reactivating Medicaid 30 days prior to release. While no services can be billed to Medicaid during this period, this enables people to have uninterrupted coverage when they return to the community; this feature is currently limited to the state correctional system. Although this advance was an important step toward bridging the gap between correctional and community healthcare, it does not allow for the kind of transitional care that is so critical.

This waiver would allow for that transitional care to happen in the last 30 days of incarceration, so that a community healthcare provider can come into the prison to meet with a patient, ensure that they have their prescriptions ready to go, and make a plan for their healthcare upon release. This will make a huge impact on patient engagement and continuity of care. It will certainly save lives.