‘Is This The Guy?’

Police and prosecutors claimed facial recognition technology wasn’t at the center of a shoplifting case, but defense attorneys say it was the sole basis for probable cause to arrest.

In February 2018, a man attempted to steal a package of socks from a New York City department store. The store’s loss protection officer said when he confronted the man, he pulled out a box cutter knife and then ran off with the merchandise.

An NYPD detective assigned to the case obtained still images of the suspect from the store’s surveillance system. Two weeks later, the NYPD’s Facial Identification Section ran the images through the department’s facial recognition software program, that compares still images to thousands of mugshots stored in its database. The search generated a series of matches.

Police records show the detective took an image of one of the matches and then texted the loss prevention officer—the sole witness in the case—and asked, “Is this the guy?” The loss prevention officer texted back that he believed that the image was of the shoplifter.

The detective distributed a wanted poster to local patrols. In April, the man identified by loss prevention officer, a Bronx resident named Andre, was arrested and charged with the theft. (Andre’s attorneys at the Bronx Defenders requested that his real name not be used in order to maintain their client’s privacy.)

Tech experts and academic researchers are questioning the accuracy of facial recognition technology. A 2019 MIT study of Amazon’s Rekognition software found that the program identified the gender of light-skinned men almost 100 percent of the time, but it mistook women as men 19 percent of the time and darker-skinned women for men 31 percent of the time.

To date, three U.S. cities—San Francisco, Oakland, and Somerville, Massachusetts—have banned the use of facial recognition technology altogether. Cambridge, Massachusetts, is considering a ban.

But the NYPD widely uses facial recognition technology. A May report from Georgetown Law’s Center on Privacy and Technology found that when the NYPD investigated a 2017 theft of beer from a CVS, a detective noted that the suspect resembled Woody Harrelson and then submitted a photo of the popular actor to the face recognition algorithm in place of the suspect’s photo.

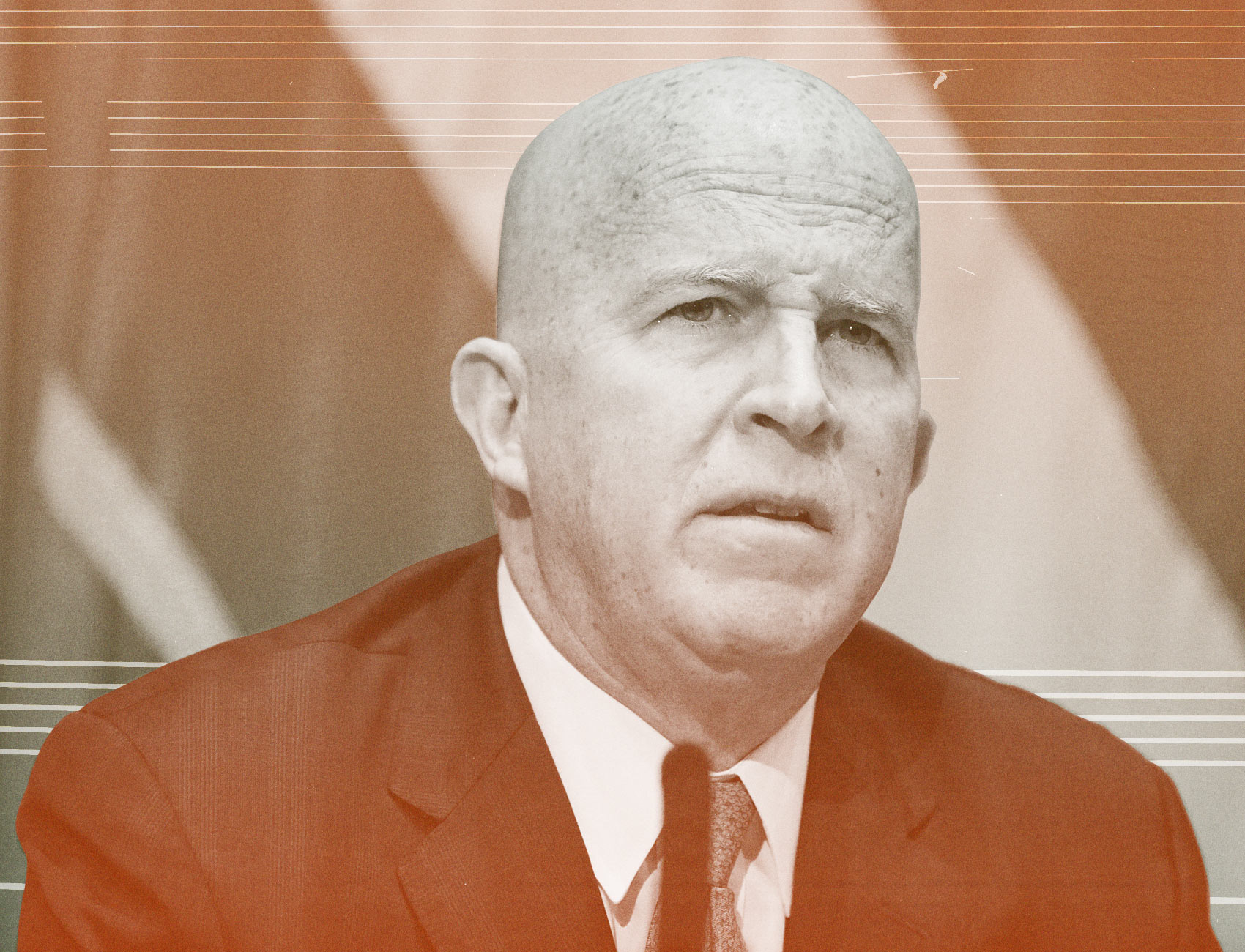

In a New York Times opinion piece in June, Commissioner James O’Neill nonetheless championed last year’s results from the department’s facial recognition software, which he said generated 1,851 matches based on 7,024 requests and led to 998 arrests.

O’Neill said his detectives safeguard their investigations by never using facial recognition matches as the sole basis for an arrest. After the system generates a match, he wrote, an “investigator proceeds with further research.”

“No one can be arrested on the basis of the computer match alone,” O’Neill added.

This month, O’Neill acknowledged that “there’s been some controversy about facial recognition” while insisting “we use that as a lead. That’s not probable cause. We’re not locking up anyone based on a facial recognition hit.”

But Andre’s attorneys argue that is exactly what happened in his case.

“In order to say our case was not based on facial recognition is to ignore reality,” said Alice Fontier, managing director of the criminal defense practice at Bronx Defenders.

She added that given what she knows about Andre’s case, what O’Neill wrote in his Times op-ed is “incredibly misleading, if not false.”

Andre’s case demonstrates how little the NYPD is willing to share about its facial recognition system.

His attorneys argued that facial recognition system was not merely a lead in the investigation; instead, they said, the match generated by the software served as probable cause to arrest their client. “No live lineup or photo pack was ever conducted. The single photograph produced by the FIS and then identified via text message is the sole basis for probable cause to arrest,” the attorneys wrote in a motion to suppress.

The defense further claimed the identification process in his case was unfairly suggestive. They argued that rather than placing Andre in a live lineup or showing the witness an array of photos to have him pick out the person he believed attempted to shoplift from the store, the detective simply texted one photo to the loss prevention officer and asked: “Is this the guy?”

In the months before Andre’s December 2018 trial, his attorneys requested that the court hold a hearing to examine whether the identification should be thrown out. They also made a long list of discovery requests for information about the NYPD’s facial recognition system.

Police and prosecutors from the Bronx district attorney’s office fought back. The NYPD rejected the idea that Andre had the right to review its use of facial recognition evidence in this case; the department said the facial recognition match did not provide the probable cause for his arrest. In court filings, police claimed that Andre was known to the loss prevention officer and that facial recognition was merely used to “put a name to a face.”

“Like eye-witness testimony, video surveillance or statements collected, a facial recognition match serves as one piece of a larger investigation. It is a lead, not probable cause and it was not used as probable cause in this case,” NYPD spokesperson Devora Kaye told The Appeal.

Kaye added: “the loss prevention officer was familiar with the defendant as he had seen him in the store on prior occasions. Facial recognition serves as a valuable investigative tool and helps the Department apprehend perpetrators of violence. In this case, facial recognition was used appropriately as a lead. To suggest otherwise is simply a distortion of the facts.”

(The Bronx DA’s office declined a request to comment for this story).

Furthermore, the police said it was unnecessary to examine the department’s investigative steps in this case because prosecutors did not intend to call officers to testify or introduce the facial recognition match as evidence.

The NYPD also claimed that it was exempt from disclosing information about its facial recognition technology because doing so could imperil future investigations. It argued that because the department is only a user—not the creator—of the software, any disclosure would violate state protections of its partner’s trade secrets.

Fontier called this argument “absurd” and disputed the claim that Andre was known to the loss prevention officer. “If that is the basis, by that rationale, they could use that argument for anything — ‘we can’t tell you how or if it’s functioning because it’s not ours, we’re just using it,’” Fontier said.

The arguments over facial recognition technology in Andre’s case were never resolved. On the day that trial was about to begin, Bronx prosecutors decided to significantly reduce the charges against him from a felony to a misdemeanor with a sentence of time served. Andre had already spent several months in jail, so he took the deal rather than go to trial and risk significantly more jail time. Still, Fontier said she believed the police were “misleading” about how important facial recognition was to their case.

“My experience is if they are misleading in one case, it’s happening in others,” she said. “We just don’t know.”