Inspired By Her Own Experiences, Baltimore Woman Publishes Magazine Giving Voice To The Incarcerated

Tia Hamilton’s State v. Us focuses closely on the criminal legal system, especially as it applies to people of color, who are statistically overrepresented in the carceral system.

Every year, 650,000 people return from prison. In The Return series, we will share some of their stories.

The editor’s note that greets readers of the latest edition of Tia Hamilton’s self-produced magazine, State v. Us, fully captures the spirit of the formerly incarcerated publisher and her message to those who’ve walked similar paths: “Four walls may hold your body, but it does not have to keep your mind.”

Inspired by her own experiences of incarceration and the stories of other people with similar experiences, Hamilton began devising State v. Us in 2017 as a way to elevate the voices of those who have been incarcerated. Since then, she has released four volumes with a fifth in progress, and has worked hard to secure distribution in both correctional catalogs and the United States at large.

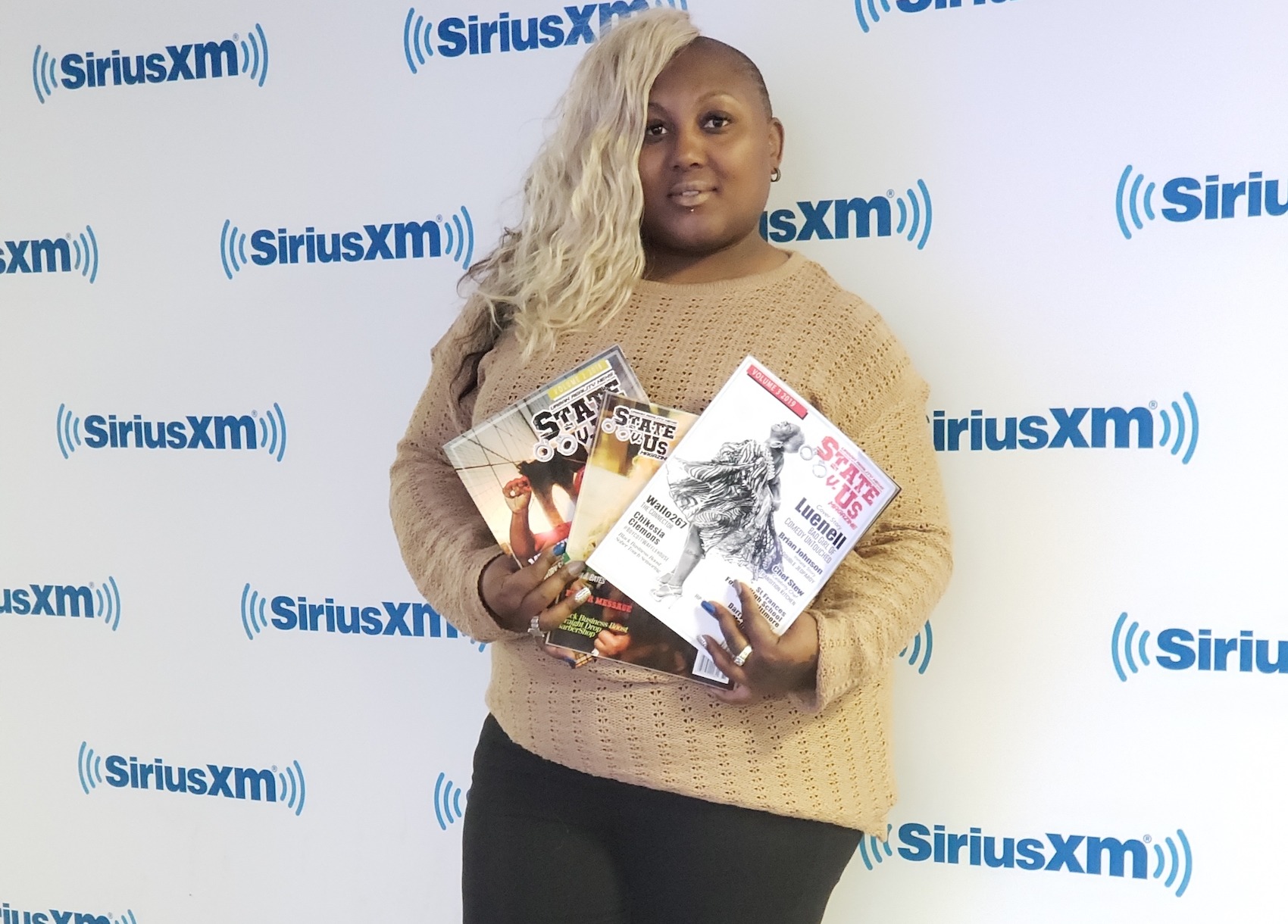

Hamilton, who also writes under the moniker “Mz. Konnoisseur,” sports a long, bleach-blond undercut and a vibrant, confident energy that draws attention seemingly without trying. She is quick to speak her mind, especially if she encounters injustice. That characteristic, along with her gregarious smile and easy laughter, invites admiration. It’s hard to imagine her as a woman who was once charged with kidnapping and attempted murder, or who ran an interstate drug ring—but she doesn’t hide from her past. She says that history with gang life and incarceration helped prepare her to run multiple businesses.

“If you ever sold drugs to a high level, you can run a company. If you ever run a block, you can run a company,” says Hamilton, who also produces an online sports talk and hip-hop radio show and just opened a bookstore in Baltimore that celebrates Black authors. “We’re sitting at the boardroom table but we’re on a street corner. That street corner is our boardroom.”

Hamilton, 42, decided to walk away from street life after an attempted murder charge against her was dropped in 2007. She says she had fought back against an ex-boyfriend when he assaulted her, but because he ended up hospitalized, she caught the charge. Before her case could go to trial, Hamilton turned to prayer. “I promised God, ‘if you get me out of here, I won’t sell no more drugs. I will act right and get my life together,’” Hamilton says. A concurrent kidnapping case against her, which involved someone she had been associated with as part of her drug business, was moved from a felony to a misdemeanor, with five years of supervised probation and no further jail time. She was behind bars and away from her son for seven months.

Hamilton acknowledges that it wasn’t an instantaneous change. She doesn’t offer specifics, but says it took her six or seven months to get her affairs in order and break away from gang life.

“Once that got in place, I haven’t sold drugs, haven’t gang banged,” she says. “Am I [still] connected to the streets? Absolutely. Related to the streets? Absolutely.”

It’s this relationship with the streets and with her past that drives her to advocate for people still trapped in the cycle of incarceration, release, and recidivism promoted by carceral supervision, and discrimination against people with felony convictions.

“She was always creative,” says Gloria Foster Williams, Hamilton’s mother and a co-owner of the new bookstore, Urban Reads. “In school she always wanted to be in charge, run things, be the boss, and tell people what to do.”

Williams recounts the challenges that arose from Hamilton’s strong-willed resistance to authority when she was younger, and the difficulties of raising Hamilton’s young son during the several months of her incarceration. But it’s these same traits that now allow her to self-publish State v. Us. Williams and Hamilton both attest to the strength of her vision, and how determined she has been to see her project come to life.

Each edition of State v. Us is adorned by a glossy, full-color cover, and printed on thick, coated pages. Those sturdy pages are one of the subtle ways that Hamilton is constantly considering her incarcerated audience.

“In prison you can share it with 20 people and it will come back to the [first] person the same way you left it,” she says. Included in each volume are detailed interviews featuring the successes of formerly incarcerated people, backstories behind famous cases, and opinion pieces on subjects like the school-to-prison pipeline. Some of the people interviewed are currently incarcerated. Most of these are men, Hamilton acknowledges, despite outreach she has made to hundreds of incarcerated women.

“I get women on the outside that are interested but when they’re locked up, I think they’re ashamed,” Hamilton explains, adding that many incarcerated women have histories of trauma that carry feelings of shame and low self-esteem.

Most of the State v. Us’s stories revolve around the criminal legal system, especially as it applies to people of color, who are statistically overrepresented in the carceral system. Some of the magazine focuses on the Black community more generally, like the way mental illness is often stigmatized among people of color, or images of Black models—many tattooed and curvy like Hamilton herself—who deviate from conventional beauty standards imposed by mainstream publications.

State v. Us generates some ad revenue, but the magazine is mostly self-financed. It’s a labor of love for Hamilton, and she wants to keep it that way. She accepts donations but is clear that her vision for the product will not be swayed. “I control my own narrative,” she asserts.

Hamilton’s email and Facebook messenger inboxes are often flooded with notes from people thanking her for her work. For people who are incarcerated, it’s a lifeline—a way to keep up with the outside world and to also be heard by that world.

Keeping the magazine independent requires enormous effort. Hamilton’s team is small; she cites a transcriptionist and a couple of designers as the core crew. She publishes some contributing writers, but most of the content, especially the interviews, is written by Hamilton herself. She manages most of the distribution efforts too, with occasional help from her mother. Each quarterly volume takes about three months to put together from start to finish. The magazine is now available in a number of bookstores and on newsstands across the United States, and in several prison catalogs.

“People in prison need a voice, and that voice is a lot of times through publication and literature,” says Hakim Hopkins, the owner of Black and Nobel, a Philadelphia bookstore that carries State v. Us. “I thought it was a cool thing for her to support, the people that are actually forgotten about [in prison].” Hopkins adds that he also chooses to support Hamilton’s work because he admires her undaunted ability to thrive, even when faced with personal adversity. “You can’t create that type of person; that type of person is born. She’s a born winner.”

Hamilton has no intention of stopping with State v. Us. This year, she and her parents combined their funds to found Urban Reads, which celebrated its grand opening on Dec. 15. It features a collection of works by formerly and currently incarcerated people. Hamilton says those books are available on sites like Amazon but just don’t get enough eyes on them.

“I created a space for Black authors to sell our books in the Black community,” she says. Hamilton also plans to offer computer access to community members, creative writing classes, and book signings featuring Black authors at the bookstore.