In Portland, A Mother Sues For Answers About Why The Police Killed Her Son

On the morning of February 9, 2017, 17-year-old Quanice Hayes knelt on the ground in front of heavily armed Portland police officers as they yelled instructions at him. “Stay down on your knees,” they told him. “Move towards us.” A police dog barked. Hayes, who was unarmed, reached down toward his waistband. Why? We’ll never […]

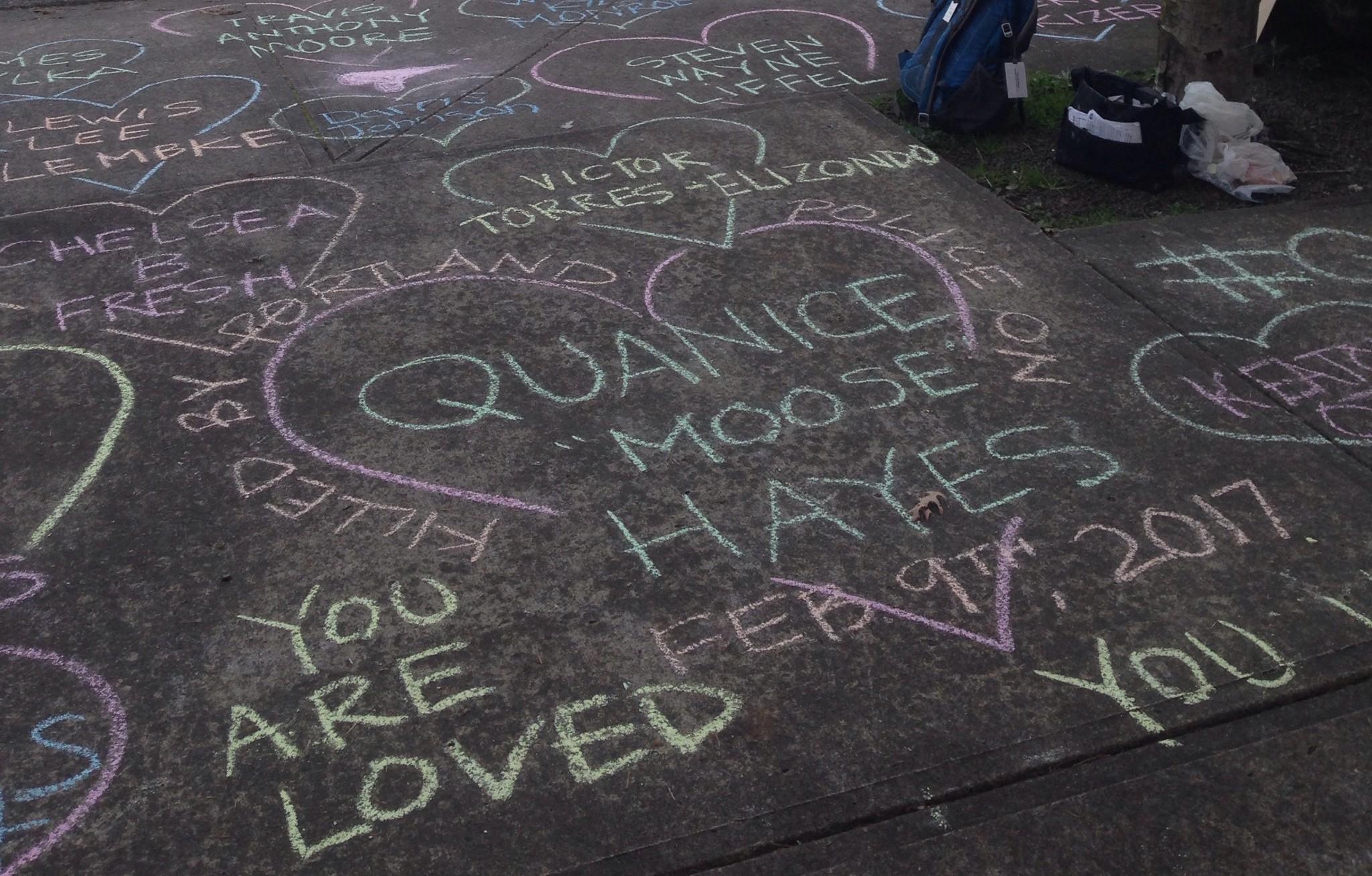

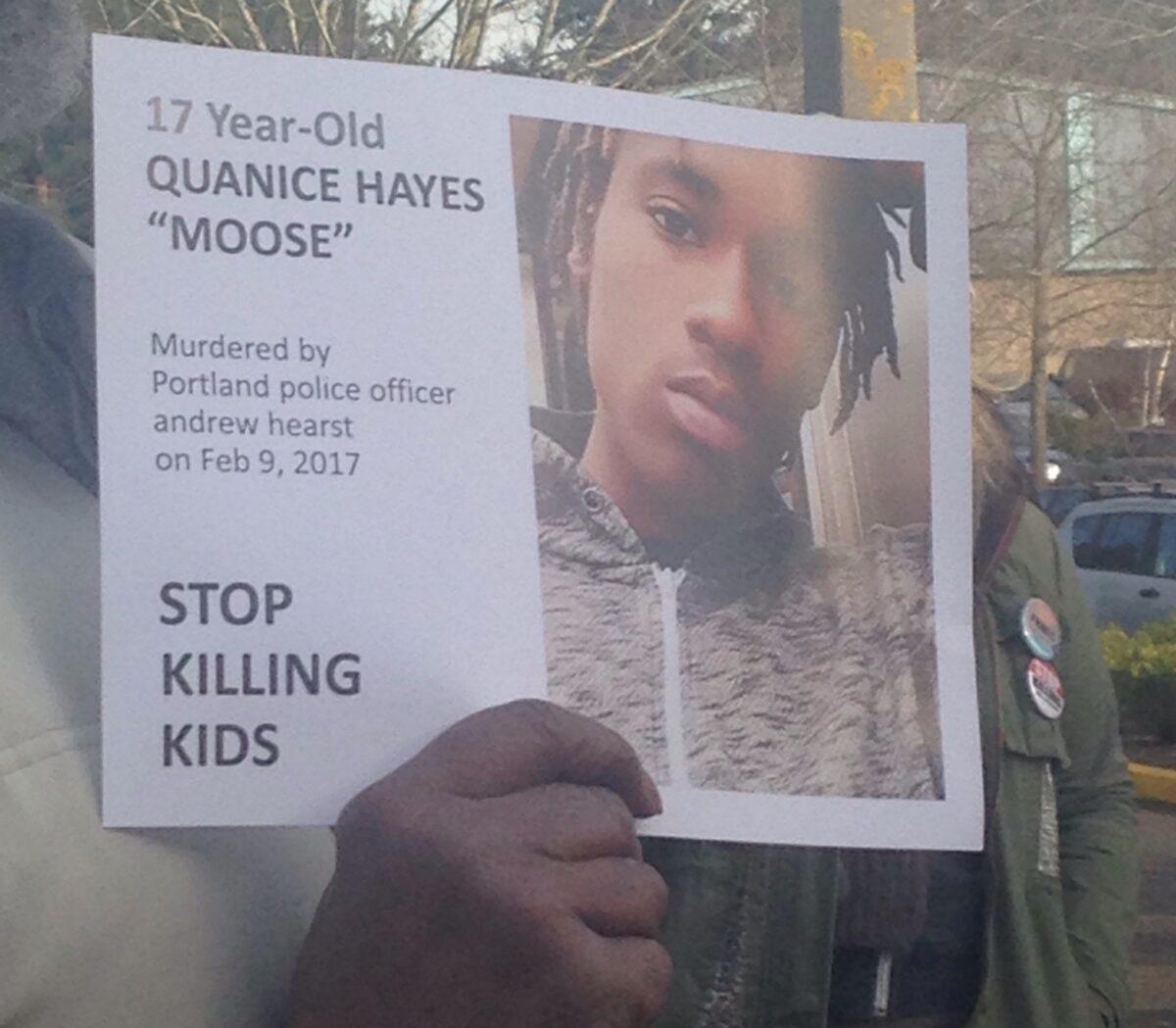

On the morning of February 9, 2017, 17-year-old Quanice Hayes knelt on the ground in front of heavily armed Portland police officers as they yelled instructions at him. “Stay down on your knees,” they told him. “Move towards us.” A police dog barked. Hayes, who was unarmed, reached down toward his waistband. Why? We’ll never know — Officer Andrew Hearst shot him in the head with an AR-15 rifle and Hayes died instantly.

In the days that followed, police officials painted a sinister portrait of the African-American teenager in local media: He was on the run after a string of robberies, they said at the time. A fake gun was found a few feet away from Hayes, they claimed. A call to 911 allegedly referred to Hayes as armed.

By the time police officers testified in front of the grand jury a month later, they said they were certain Hayes was armed and dangerous as they surrounded him in the front yard of a home where Hayes had been hiding, even after he told the officers, “I don’t have anything on me.”

“There was no doubt in my mind the person that I was looking at had a gun,” Officer Hearst told the grand jury.

Moments before the shooting, Hearst said he told Hayes repeatedly, “If you reach for your waistband, I will shoot you.” Hearst said he grew frustrated.

“We told you to crawl,” he recalled telling Hayes at the time. “How could you have gotten that wrong?”

The witnesses to the shooting who testified in front of the grand jury were all law enforcement officers, and prosecutors from Multnomah County District Attorney Rod Underhill’s office repeatedly played up the danger that Hayes posed, even though officers on the scene admitted that they never saw Hayes with a gun.

“I knew that if he were to get to his gun, I would not be able to react fast enough before he was able to shoot one of us,” Hearst testified. “So it was absolutely a conscious decision on my part to defend myself, my coworkers and any citizen that might be behind me from the threat of him getting that gun out and shooting us.”

The grand jury members had no questions for Hearst after an assistant district attorney completed his questioning. They decided, as in so many other cases across the country where police officers have shot unarmed Black and brown people, not to indict Officer Hearst, who faced no further disciplinary measures for the incident.

Each year, there are approximately 1,000 police shootings in the United States, according to recent research by Bowling Green State University professor Philip M. Stinson. Stinson told The Appeal that since the beginning of 2005, there have only been 84 police officers who have been arrested for murder or manslaughter resulting from an on-duty shooting where the officer shot and killed someone. Of those 84 officers, according to Stinson, only 32 have been convicted of a crime resulting from the on-duty shooting, with the vast majority of those convictions being for a lesser offense than murder, like manslaughter.

Since the grand jury deliberations last year, the Hayes family has been given no further information from the district attorney, city of Portland, or the police regarding Quanice’s death.

So on February 7, lawyers for the Hayes family sent a notice to the city of their intent to sue, charging that Portland is “a city where young Black men are discriminated against at every stage of their interactions with police and the criminal justice system.” The family is requesting information like 911 call transcripts, photographs of the scene, and police reports, evidence that would have come out during a criminal trial but did not emerge during the grand jury proceedings controlled by DA Underhill.

“Families of the victims of police shootings are just so disempowered and frustrated by the process,” said Portland-based attorney Ashlee Albies, who, along with Jesse Merrithew, is representing the Hayes family. “Deep down, many of these families know that they’re not going to get an indictment of these officers, but they still hope for it and when the police talk to the families to do the quote unquote investigation, the families believe it. They need to believe it.”

The families often hope that if the truth comes out, it will help spur reform, Albies said. “At least finding out what went wrong, to try to use that as a leverage point to change policy, to change training, change practices so this doesn’t happen to somebody else and no one has has to go through something like this.”

Last Thursday, a consultant working on behalf of the Portland City Council released a report criticizing the Portland police department for its handling of six officer-involved shootings between 2014 and 2015. In one case, the department allowed officers to view video evidence of an officer-involved shooting scene before speaking to internal affairs investigators. The consultant also blasted prosecutors for asking “leading” questions during one grand jury hearing that seemed intended to portray the shooting victim in a more criminal light.

The Hayes family is crowdfunding $20,000 to help pay for the first part of the lawsuit, which would cover filing fees, some initial depositions, and retaining experts. The family was told by Albies and Merrithew that the lawsuit, even without lawyers’ fees, could cost as much as $150,000.

Terrence Hayes, Quanice’s cousin, has played a large role in advocating for the family’s interests in the case. He said high costs and massive logistical barriers keep families like his from getting basic answers about police-involved shootings and present an enormous obstacle to justice.

“This further establishes to me the system would rather see a poor family spend every last cent of theirs fighting a district attorney with the purse of the county then reveal the truth,” Terrence told The Appeal. “I shouldn’t have to hope to raise some astronomical amount of money in the hope that some information will finally come out. You would think the district attorney would have enough belief in the evidence to release it on their own, to just say, ‘We believe what happened was right and here’s the evidence.’”

Terrence believes the fate of the case was sealed by the flawed grand jury deliberation, where the DA’s office reversed its traditional role in the criminal justice system and actively worked against an indictment.

“When the DA is trying to find someone guilty, they don’t call witnesses who are there to try to prove your innocence,” Terrence said. “That’s just ridiculous. But for police officers, for some reason, fellow police officers, their captains, their trainers, everybody who will continue to fight for the protection of police officers is allowed to make a case on their behalf. The grand jury process was a sham.”