In Pennsylvania, Defendants Pay A Fee Just To Plead Guilty

The ‘plea fee’ stems from a state law passed in the 1980s and can cost nearly $200, depending on the county.

On Dec. 16, 2017, Fairview Township Police in York County, Pennsylvania, arrested then 34-year-old Dustin Wyar after he was found intoxicated and in possession of a small amount of marijuana in his car in the parking lot of a local diner.

He ultimately pleaded guilty to charges of possession of marijuana and possession of drug paraphernalia, and was sentenced to 12 months and 30 days’ probation. Wyar was also ordered to pay nearly $1,000 in fines and fees, more than $160 of which went toward a “plea fee.”

Similarly, in 2016, a Cumberland County woman pleaded guilty to three retail thefts, in which about $25 in merchandise was stolen, and was then hit with nearly $600 in plea fees.

Depending on the county, Pennsylvania’s plea fee can cost a criminal defendant nearly $200. The plea fee is exactly what its name suggests: a fee for the simple act of pleading guilty. It stems from a state law passed in the 1980s, and it must be at least $20 and no more than $75. County clerks of court set the initial fee within that range but have the discretion to increase it every three years, which is why it has risen to $164 in York County. A slightly more costly trial fee is imposed if a defendant chooses to go to trial and is convicted. Money derived from the fee is meant to fund county clerks of courts, independent elected officials who oversee and maintain records from the criminal justice system.

“We’re funding public offices by taxing the poorest people, but it doesn’t show up as a tax,” John Pfaff, a professor at Fordham University School of Law, told The Appeal. “It shows up as a fee. It allows our taxes to look more progressive than they are.”

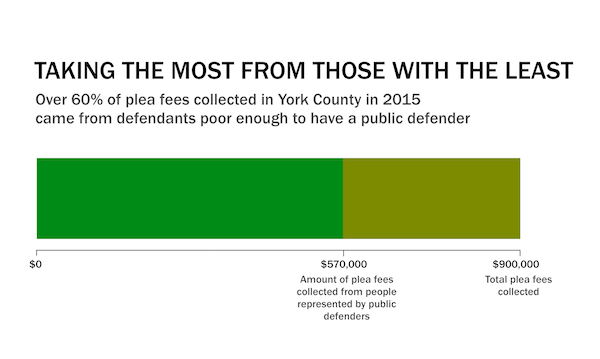

As is the case with most criminal court fees, Pennsylvania’s plea fee is disproportionately leveled against poor people. In 2015, more than $900,000 in plea fees were imposed in York County, according to a review of all criminal dockets by The Appeal. More than $570,000—or roughly 60 percent—of those fees were charged to people who were represented by a public defender.

Plea fees were assessed on nearly 80 percent of all new cases in York County that year. The Appeal reviewed the York County budget and found that the fee could be eliminated with a small tax increase. The clerk of courts office could be fully funded with a less than 1 percent tax increase, which would raise the average real estate tax bill less than $10 annually.

But even if the plea fee is eliminated, there are still other fees that can be imposed on Pennsylvania defendants. For example, if a criminal case is dismissed, a state rule allows the imposition of fees and restitution.

The Appeal also identified numerous cases in York County where criminal charges were dismissed but the defendant was still assessed a plea fee. In several cases, the plea fee alone accounted for more than 40 percent of what the defendant had to pay to the court.

The stress of debt tacked on to a defendant’s criminal court proceedings makes it more likely that they will commit a new offense, Pfaff said. “Everybody’s ability to control their behavior declines with stress,” he added. “You don’t understand what it’s like to suffer under crippling poverty, and if you’re spending every minute thinking about how are you going to pay next month’s rent or how are you going to get food for your kids, all while having to pay this additional fine on top of that, it makes it harder for anyone to self-regulate.”

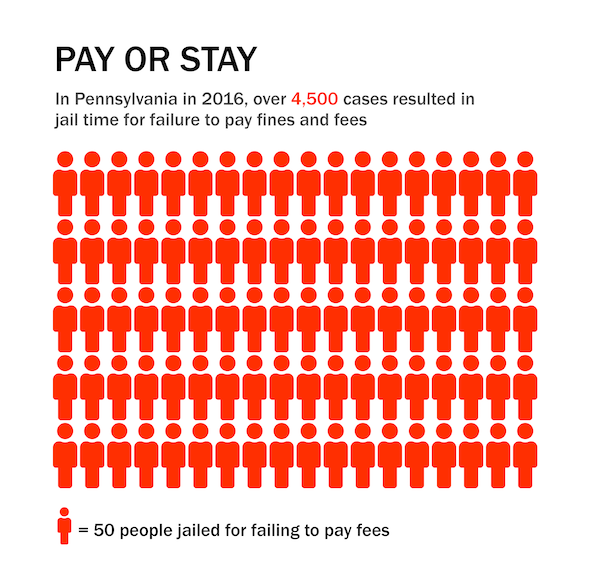

Failing to pay court debt can have other serious consequences, too. In Pennsylvania, a defendant can have their driver’s license revoked, face a civil judgment and debt collection, or even be put in jail for failing to pay court-imposed debt.

A recent Pittsburgh Post-Gazette investigation found that in 2016 more than 4,500 cases where defendants were jailed for failing to pay their court debt in Pennsylvania. More than 340 of those cases were in York County.

People say “‘don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time,’” Pfaff said, “but that completely ignores our decision to underfund social services across the board, which contributes to people criminal behavior.”