Immigrants Share Horror Stories From Inside Massachusetts’s ‘Worst’ Jail

“Jail is not a country club,” the Bristol County sheriff said. “That’s why once you’ve done time in the Bristol County House of Corrections, you won’t want to come back.”

Conditions in one Massachusetts jail being used to hold ICE detainees are abusive and dangerous, according to former detainees.

Three people told The Appeal that their time at the Bristol County Jail was marked by poor conditions and abusive behavior from guards.

Siham Byah, a Boston-based community activist who was recently deported to her native Morocco, said that she was placed in the corrections facility instead of the closer Boston South Bay detention center because of her political activism—the same reason she claims she was deported.

“I was put there, it is my guess, to hurt my support system,” Byah said by phone from Morocco, “and because Bristol County is known as the worst prison in Massachusetts.”

After she was placed in the women’s section of the Bristol County Jail while she awaited detention proceedings, Byah said she began a hunger strike to protest her arrest and detention. As a result, the guards put her in segregation.

After about three and a half days, Byah broke the strike. She claims that the guards told her they would force her to eat if necessary because ICE would not tolerate someone dying in the facility.

“They said they would strip me, tie me down, and then shove food down my throat,” said Byah.

The Bristol County Sheriff’s Department denied the majority of Byah’s allegations. Jonathan Darling, the county sheriff’s office public information officer, told The Appeal that Byah only spent one day in solitary so guards could “monitor her meal refusals and health better.”

“In the rare case that a hunger strike becomes a serious threat to an inmate or detainee’s health after weeks of refused meals, a judge is the one who decides if we force feed the individual,” Darling said, adding that Byah’s accusation against jail guards was “completely and 100 percent false.”

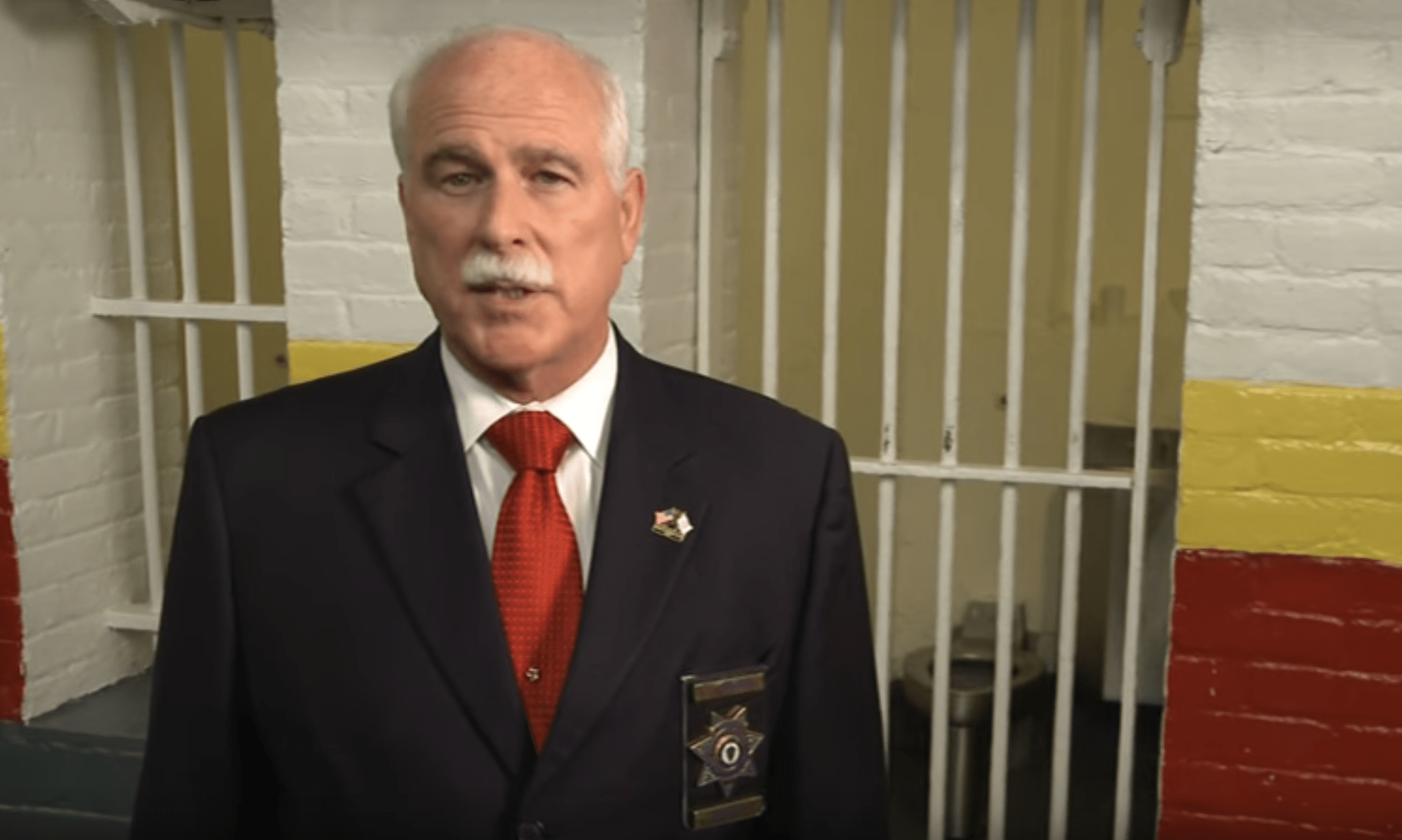

Sheriff Thomas Hodgson has proudly instituted a culture of harsh punishment at the facility.

“Jail is not a country club,” Hodgson said in a 2010 campaign ad. “That’s why once you’ve done time in the Bristol County House of Corrections, you won’t want to come back.”

Hodgson’s reputation as a tough jailer—he offered to provide prison labor to help build President-elect Donald Trump’s wall on the Mexican border in early 2017—has earned him some unwanted attention recently: Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey called for an investigation in June into conditions at the jail after reporting by the New England Center for Investigative Journalism found that roughly a quarter of all in-jail suicides in Massachusetts occurred at Bristol County Jail, which holds only 12 percent of the state’s county jail inmates. Hodgson dismissed the reports of dangerous conditions at Bristol, and implied that the attorney general had targeted him because he was a conservative. He demanded an apology from her.

Bristol holds ICE detainees through a 287(g) agreement, a federal program that allows ICE to subcontract detention of undocumented people to local municipalities. The program is used across the country. ICE officials told The Appeal that the agency takes a proactive role in ensuring that detainees are treated appropriately.

“The agency’s aggressive inspections program ensures its facilities comply with applicable detention standards, and detainees in ICE custody reside in safe and secure environments and under appropriate conditions of confinement,” ICE spokesperson Khaalid Walls said via email. “Based on multi-layered, rigorous inspections and oversight programs, ICE is confident in conditions and high standards of care at its detention facilities.”

In the most recent inspection on file, from 2016, ICE’s Office of Detention Oversight found that detainees had a number of complaints about medical care, including finding that “in six of the ten mental health records reviewed the facility failed to obtain informed consent from detainees receiving psychotropic medications.” And the report lists other detainee complaints that reflect what the people who spoke to The Appeal said about the facility, including aggressive treatment by guards and nearly inedible food.

“These allegations are completely absurd,” Darling responded in an email. “Our facility is nationally accredited by the National Corrections Association and regularly audited/inspected by ICE and the state Department of Corrections.”

ICE detainees are held in three areas in the jail. Men are held in two large, open rooms in the C. Carlos Carreiro Immigration Detention Center, a large building not connected to the jail, and held in the jail proper. Women are mixed with the general population. Although ICE holds detainees in the facility, it has little control over the day-to-day operations and does not have staff on site all the time—detainees are watched by jail guards in the detention center and the jail.

Detainees are supposed to be held in different areas according to their criminal record, said Matt Cameron, a Boston attorney specializing in immigration litigation. There are three levels of criminality: The two higher levels, where detainees have a record of misdemeanors to felonies, generally land offenders in the jail, while low-level offenders or nonoffenders are in the detention center.

“Bristol County House of Corrections houses detainees for ICE in two ICE-only units and commingled with pretrial county detainees,” said Walls.

Cameron said most people entering ICE detention at the jail are booked on minor offenses, most likely because of the Trump administration’s focus on criminalizing all immigration violations. That results in people who aren’t a threat to the community rubbing shoulders with citizens awaiting trial for criminal offenses and detainees with violent records as space in the detention center runs out and the jail puts people where it can.

One former detainee who asked to be identified only as “D” to avoid retaliation as he navigates the immigration system was held in the jail with detainees and prisoners, and faced the full force of the conditions that Hodgson has made his name on. Detainees and prisoners are separated during regular hours — D described it as one group in each half of the room — but mingle during eating time and recreation.

“They treated us just like the prisoners,” said D.

Immigrant detainees in the jail face the same disciplinary consequences as the prisoners. One of the punishment tactics is disciplinary segregation, or solitary confinement. Administrative segregation, which also results in solitary confinement, is generally used for the protection of people in custody—though it can be abused (what Byah claims happened to her because of her hunger strike). According to the regulations ICE uses at Bristol, the Performance-Based National Detention Standards, use of disciplinary segregation is only for the most severe infractions of jail policy, and should be avoided whenever possible.

But that’s not the way segregation is used at Bristol, according to Byah. The second time Byah said she was sent to solitary it was for one day as punishment for arguing with a guard over using a telephone at break time. Byah said she knows of women in ICE detention at the jail who have spent upwards of a week in segregation.

“ICE detainees who do not follow the rules of the institution, including assaulting other inmates, detainees or officers, or other offenses,” Bristol’s Darling said, “are subject to the same disciplinary action as the rest of the jail population, which can include spending time in a segregation unit.”

D, who was at Bristol for six months, told The Appeal that guards at the jail regularly used solitary confinement as a punishment. “They’d lock them up for a month, sometimes a week,” he said. “It depended on what a person did.”

Solitary was used in the detention center as well, said J, a former detainee speaking on condition of anonymity who was held at the facility for a month in the fall of 2017 and is fighting his deportation. He described seeing detainees being put into segregation for not coming immediately when called or, in one case, for (nonviolently) expressing frustration with a guard’s behavior.

“When a guard felt like it, they found something very minor,” said J.

The conditions in the detention center are hardly better than in the jail itself, said lawyer James Vita, a public defender for the Committee Public Counsel Services. Medical care access—when prisoners have it—is access to what Vita termed “medieval style” health care. J said people held In the detention center waited days for medical attention. Fevers and toothaches were ignored and medical conditions are often neglected, said J. In one case, he said, an epileptic detainee wasn’t given his medication, resulting in a seizure that ended with him falling off his bunk and injuring himself.

“There is a medical professional in every housing unit and facility every day,” said Darling.

There were no diagnostic tools beyond a stethoscope in the medical bay, said Byah, and the nurse on staff was at best disinterested. When detainees would go to medical, they would have to stay in the bay overnight—a new and unfamiliar cell. Cameron, the immigration lawyer, called this overnight holding a form of punishment, a perception shared by Byah.

“You were torn between having a medical problem and not wanting to go to the med bay,” said Byah.

Hygiene, too, was a concern, D said. He told The Appeal that the area he was held in had only one toenail clipper for the people in that part of the jail. The bathrooms were filthy, D said, and the showers were dirty and moldy.

It was the same situation on the women’s side, Byah said.

“You can clearly see calcification of old filth accumulating on showers and bathrooms and even floors,” she said.

One ICE agent made occasional visits, according to the three former detainees that talked to The Appeal. He spoke only English, said Byah, and threatened to use segregation against detainees.

“Bad News Larry,” as D referred to the agent, never had anything helpful to say. Rather, he only told detainees that they would most likely be deported sooner than later.

When asked whether ICE’s agents were aware of the conditions in the facility, Walls told The Appeal that detention centers are well monitored.

The former detainees said there was nobody to bring their concerns to. With seemingly nobody to turn to for help and a seemingly uninterested regulatory body in charge of the detention center, detainees at Bristol are isolated. Although ICE regulations mandate that the agency’s detainees have access to programs and facilities that are available to other prisoners, Cameron says his clients have been unable to use the library at Bristol County Jail. That treatment makes Cameron uncomfortable, especially in light of the sheriff’s comments about Mexican immigrants.

“Bristol really seems to be reflecting Hodgson’s view on his approach to immigration,” said Cameron. “I’m not seeing a lot of humanity there.”

The human rights group Freedom for Immigrants released a report documenting racial abuse in ICE detention centers in late June. The report named Bristol County House of Corrections one of the sites where detainees were subjected to racial abuse and discrimination. Detainees were called “baboons,” the report claimed, and told by guards that nobody would believe their complaints.

Darling denied the allegations in the report, citing a conspiracy against the jail.

“This is a case of either a detainee lying to drum up sympathy for his/her cause,” Darling said, “or an organization like the report’s author lying to advance its own pro-illegal-alien political agenda.”

With conditions in the jail that are approaching torture, said Byah, the time to end ICE’s contract with Bristol is long overdue. But, she added, that can’t be the end of the story.

“That place needs to shut down, as does the whole program all together,” said Byah.