I was Raped. And I Believe The Brock Turner Sentence Is a Success Story.

The plane’s voyage was commissioned by feminist group UltraViolet to protest former Stanford swimmer Brock Turner’s six-month sentence handed down by Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Aaron Persky in 2016 for sexually assaulting an unconscious woman on campus the previous year. The sentence ignited an outcry and an effort to recall Judge Persky.

On the morning of June 12, 2016, a small plane circled over Stanford University’s commencement ceremony trailing a banner reading, “Protect Survivors. Not Rapists. #PerskyMustGo.”

The plane’s voyage was commissioned by feminist group UltraViolet to protest former Stanford swimmer Brock Turner’s six-month sentence handed down by Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Aaron Persky in 2016 for sexually assaulting an unconscious woman on campus the previous year. The sentence ignited an outcry and an effort to recall Judge Persky. Over 1 million people have signed a petition to remove Judge Persky, and even members of Congress have joined the chorus. Now, Santa Clara County Assistant District Attorney Cindy Hendrickson is running to replace Judge Persky should his recall go before voters.

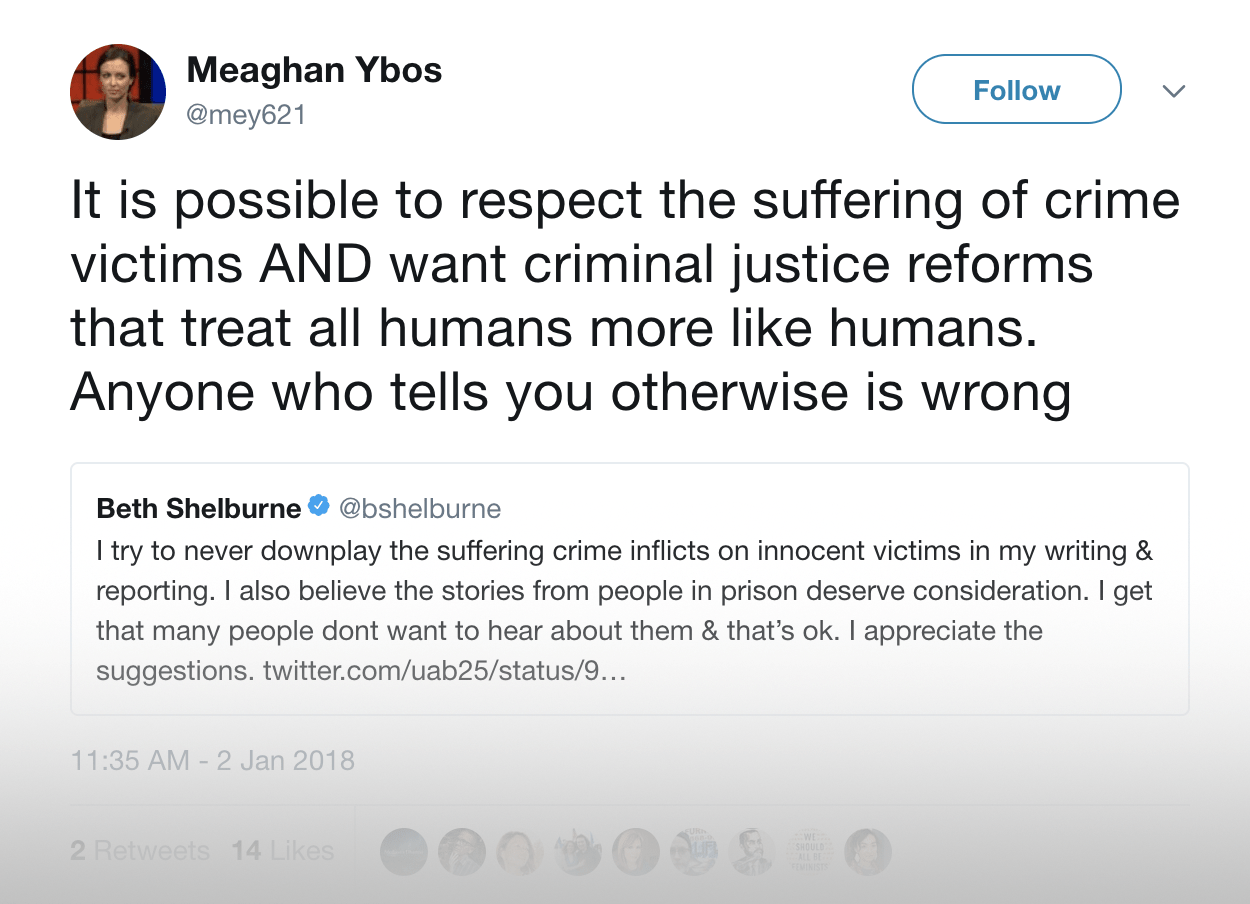

There have been a few voices criticizing the recall movement. Some have warned that the effort could threaten judicial independence by pushing judges to buckle under pressure from public opinion in individual cases. Others have warned that the recall could scare judges into giving harsher sentences to all defendants, which would likely disproportionately affect underprivileged and minority defendants. And others have pointed out that the recall effort creates a tension between feminist anti-rape advocacy and other progressive, anti-carceral social justice movements.

But with few exceptions, those critical of the scrutiny of Judge Persky have not defended Turner’s sentence. I will do so here. I am a rape victim engaged in a lawsuit against the Memphis Police Department for systematically failing to investigate rape cases and I believe that Judge Persky’s sentence was just.

The outrage over the supposedly lenient sentence misunderstands the consequences of Turner’s conviction, which includes lifetime registration as a sex offender, and vilifies individualized sentencing. I also believe that the energy and vitriol directed at Judge Persky should have been used instead to hold police departments accountable for properly investigating rape, which too many fail to do.

In a Washington Post op-ed, Stanford law professor Michele Dauber charged that Judge Persky “had to bend over backward to award Turner such a light sentence.” More recently, Professor Dauber has re-affirmed that criticism on her Twitter account, describing Turner’s punishment as a “minimum sentence” handed down to a “white affluent” athlete. Professor Dauber and many others have also mistaken the sentencing process as Judge Persky demonstrating “empathy for the criminal.” At Turner’s sentencing hearing, Judge Persky considered statutory aggravating and mitigating factors and sentencing criteria. These factors included Turner’s age (he was 19 at the time of the offense), lack of criminal record, intoxication, letters of support, remorsefulness, and — much lamented by Professor Dauber and other pundits — the effect the felony conviction would have on his life.

As is common practice, Judge Persky based his sentencing determination not on Turner’s athletic ability, gender, or race, but on the recommendation of his probation officers. Further, Judge Persky was authorized by the California Penal Code to depart from the statutory minimum sentence — two years, in this case — after considering Turner’s lack of criminal history and the effect of incarceration. Judge Persky determined that a prison sentence would have a “severe impact on him. And that may be true in any case. I think it’s probably more true with a youthful offender sentenced to state prison at a . . . young age.” Contrary to Dauber’s assertion that Judge Persky “had to bend over backwards” to lightly punish Turner, he tailored the sentence to best serve justice, not merely to churn out a one-size-fits-all sentence.

We should not demonize judges for handing out individualized sentences, even to Brock Turner. Instead, we should demand that judges use discretion more broadly and in favor of people from all backgrounds. And we must recall that the very worst criminal justice policy springs from outrage over individual high profile cases from Willie Horton to, more recently, Jose Ines Garcia Zarate, a homeless Mexican immigrant in San Francisco who was just acquitted in a high profile murder that Donald Trump seized upon in his 2016 campaign to support his anti-immigration platform.

Furthermore, advocates like Dauber have falsely characterized Turner’s sentence as a slap on the wrist, but his punishment also involves much more than the number of hours he was caged. Turner owes court fees and is required to pay the victim restitution. He must attend a year-long rehabilitation program for sex offenders, which includes mandatory polygraph exams for which he must waive his privilege against self-incrimination. If he violates the terms of his three-year felony probation, he faces a 14-year prison sentence. He now has a strike that can be used against him under California’s three-strikes law if he is accused of any future criminal activity. As a convicted felon, he will not be allowed to own a gun.

And far from rehabilitating offenders like Turner, prisons leave people “worse” than when they went in. At the Santa Clara County jail, where Turner served time, three corrections officers were charged with murder in the beating death of a mentally ill inmate; this attack was just part of a string of allegations of violence committed by the the jail’s corrections officers. If Turner had been sent to prison, experts say, it’s likely that he could have been released back into society with exacerbated mental health issues, trauma, and further exposure to crime that would result in higher odds — not lower — that he would commit future crimes.

The most severe part of Turner’s sentence, which anti-rape advocates largely have glossed over, is the requirement that he register as a sexual offender for the rest of his life. This means that an online sex offender registry will show his picture, his address, his convictions, and details of his probation. These lists, which contain people convicted of an ever-growing number of offenses, are so broad and oppressive that a Colorado federal court deemed them cruel and unusual punishment. They are “modern-day witch pyres” that often leadto homelessness, instability, and more time in prison.

As with Jose Ines Garcia Zarate and Willie Horton before him, political leaders seized on outrage over Turner’s sentence to justify punitiveness. The Turner case spurred a new mandatory minimum law in California removing the option of probation for people convicted of sexually assaulting a person who is intoxicated or unconscious. By imposing a three-year mandatory sentence, the law removes judicial discretion. “The bill is about more than sentencing,” said Democratic Assembly member Bill Dodd in a written statement following the bill’s passage. “It’s about supporting victims and changing the culture on our college campuses to help prevent future crimes.”

But it’s at the “front end” of the criminal justice system where most rape complaints falter. Police have often acted as hostile gatekeepers preventing complaints from ever reaching a courtroom. History shows police gatekeeping in cities like Philadelphia, St. Louis, Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, New Orleans, and New York City. In recent years, police have regularly closed casesbefore doing any investigation, discarded rape kits (the San Jose Police Department currently has over 1,800 untested rape kits and refuses to count the rape kits collected before 2012), and have even arrested victims for false reporting. It’s not surprising that police departments solve abysmally few rapes, with some cities’ clearance rates in the single digits.

The Turner case was investigated and prosecuted to the full extent of the law. For a sexual assault case, it is a rare success. More punishment isn’t always the best or most just response. Nor does it necessarily provide justice for victims. And as long as police gatekeeping prevents rape victims from having consistent access to the criminal justice system, recalling judges and increasing sentences will yield no progress in reducing sexual assault.

Correction: This story previously indicated that Turner’s felony conviction would preclude him from voting. This is not the case under California law and the article has been updated to reflect that.