‘I Feel The Oxygen Going Out Of My Mouth’

In October 2018, Marshall Miles was taken into custody by Sacramento County sheriff‘s deputies outside a convenience store. About 14 hours later, he was dead.

The last time LaTanya Andrews saw her son alive, he was handcuffed and seated in the back of a Sacramento County, California, sheriff’s deputy’s squad car.

On Oct. 28, 2018, Andrews received a call from a friend who heard that her son, Marshall Miles, was behaving strangely near a Power Market just outside of Sacramento city limits. Andrews dropped everything and rushed to the convenience store, where she asked officers for permission to see Miles.

“We don’t think it’s a good idea, because it may agitate him even more,” she said the officers told her.

“Meanwhile, he’s yelling in the background,” Andrews remembered. “He kept saying, ‘Mom! Please, Mom, help me! Help me!’”

The Power Market incident began when the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department and the California Highway Patrol responded to numerous 911 callers reporting that a man was jumping on top of cars at the intersection of A Street and Watt Avenue in North Highlands. Callers also said the man was attempting to rip off windshield wipers and appeared to be causing damage to vehicles stopped at a traffic signal.

One of the callers, a Power Market cashier, told a dispatcher that the man was “freaking out,” and grabbed her while she had cash in her hand. Another female caller said she observed the man standing on top of a compact vehicle and described him as appearing to be high on drugs.

The sheriff’s department later identified the suspect as Miles, a 36-year-old Black man.

At the scene, Andrews pleaded with officers to help her son. “If he was acting erratic,” she told them, “jumping on cars or kicking cars—I’ve never known him to act this way—can you please take him to the hospital?”

Andrews said the officers on the scene ignored her. “They left me standing there,” she said. “When they started driving off, I just stood there and started crying.”

Miles was first taken to the county jail. About 14 hours later, the sheriff’s department contacted Miles’s eldest sister to say her brother had become unresponsive while in custody at the jail. The department had transferred him in “extremely critical condition” to an area hospital, where the family was allowed to visit. Miles was pronounced dead sometime after Andrews and others saw him.

In the two and half months since Miles’s arrest, his family hadn’t received a definitive narrative about his death. Nearly everything that Andrews and her family know about his arrest comes from media coverage. On Dec. 3, 2018, the sheriff’s department released video surveillance footage of Miles at the convenience store, in the back of the squad car, and at the jail, which was widely picked up by local TV and print news outlets, without first giving notice to his family. The Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department posted this video to YouTube where it has been viewed more than 20,000 times; the footage is a document of an undignified death, with Miles’s pants down in much of the video.

“They never reached out to us,” Andrews said. “They never sent us any condolences. Nothing.”

A sheriff’s frayed relationship with advocates

Community leaders and civil rights attorneys say that Miles’s family’s experience with the Sacramento County sheriff’s office, which comprises roughly 2,000 employees and is one of the largest sheriff’s offices in the U.S., is not unusual. In 2017, there were six in-custody deaths recorded by the county’s Office of Inspector General. Four of those deaths occurred at the main county jail. The department also had eleven officer-involved shootings that year.

Sheriff Scott Jones, who began his career in the department in 1989 as a security officer at the main county jail, has long had a troubled relationship with Sacramento’s Black community, according to local activists. Tanya Faison, a lead organizer with Sacramento’s chapter of the Black Lives Matter Global Network, said community groups are often stonewalled by the sheriff’s department regarding complaints about deputies or officer-involved shootings. ”The sheriff has been reluctant to work with anybody,” Faison said. “We approach him in the way that we always do. So, he just says no to us. But you’ve got folks in the NAACP that sat down with him and built a relationship with him. It got to the point where none of them meet with him anymore. He’s always rude to them. He’s the worst kind of officer you could have running things.”

On Wednesday, the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California filed a lawsuit in federal court against Sheriff Jones on behalf of Faison and Sonia Lewis, co-leader of BLM Sacramento, alleging that he violated free speech protections when he deleted critical comments from his official “Sheriff Scott Jones” Facebook page and also banned them from accessing the page. “In so doing, Sheriff Jones censored plaintiffs’ voices during a critical time of public debate in Sacramento about whether and how his department should be subjected to outside oversight,” the complaint reads. Attorneys for Sacramento County sheriff’s office did not respond to a request for comment on the ACLU lawsuit.

Betty Williams, a longtime president of the Sacramento NAACP, said she had working relationships with Jones’s predecessors, but had become “frustrated” with Jones over the organization’s apparent removal from an advisory group that was intended to foster better relations between the sheriff’s department and the community.

Jones ran for sheriff in 2010 and was re-elected unopposed in 2014. In 2016, Jones ran for Congress, as a Republican, challenging incumbent Democratic Representative Ami Bera. Bera’s supporters cited news reports and complaints filed in federal court about botched investigations of misconduct at the sheriff’s department, settlements with brutality victims and frequent exonerations of problem deputies under Jones’s watch. In 2009, Sacramento County paid $170,000 to settle a lawsuit brought by a woman incarcerated at the county jail who said officials inadequately investigated allegations that a female deputy raped her more than a dozen times for nearly a year. Jones was commander of the main jail when the alleged abuse occurred. The county also paid out more than $2 million in legal settlements, largely for excessive force allegations against Sheriff’s Deputy Donald Black, including a $1.5 million payout to a woman who lost a three-inch chunk from her calf when she was attacked by Black’s K-9. Black retired from the sheriff’s department on Oct. 1, 2013, following his arrest on suspicion of child molestation (Black later pleaded no contest to the molestation charge without admitting his guilt.) Several of the incidents occurred when Jones was assistant to former Sheriff John McGinness. Ultimately, Jones lost narrowly to Bera in the House race, but in 2018 he was re-elected to a third term as sheriff.

Jones’s relationship with the Black community has deteriorated to the point where the Sacramento Bee recently compared him to Bull Connor, the civil rights era Commissioner of Public Safety in Birmingham, Alabama, who allowed Klansmen to beat civil rights activists known as the Freedom Riders. “In 2018, law enforcement officers kill African American men at a rate so alarming it should be a national emergency,” the newspaper wrote. “These deaths, and the racial dynamics underlying them, present an urgent moral crisis. This is the present-day frontier of the civil rights movement. People like Jones should be leading the way toward solutions. Instead Jones has fought to hide the truth, evade accountability, bully critics and muzzle those charged with holding him accountable.”

John Burris, an Oakland-based civil rights attorney, said the department is “a throwback” to a time when sheriffs saw their jurisdictions as fiefdoms. “In Sacramento County, in terms of the sheriff’s deputies, there’s a sense of lawlessness.” Burris has litigated numerous cases against law enforcement agencies throughout California, and he says that few in law enforcement ever face legal repercussions for excessive force, misconduct, or in-custody deaths. Burris said that in his 30 years as a civil rights attorney, he has filed at least seven cases against the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department.

In June 2017, the Sacramento chapter of Black Lives Matter sent Jones a letter seeking answers about a pair of officer-involved shootings and the alleged beating of a female motorist by deputies at the county jail. One of the cases that BLM cited involved Mikel McIntyre, an emotionally troubled 32-year-old Black man fatally shot by deputies on the shoulder of a highway on May 8, 2017. After McIntyre allegedly threw large rocks at deputies, they fired 30 shots and struck him at least seven times. In August 2018, the inspector general’s report deemed the officers’ actions “excessive” and concluded that they fired an “unnecessary” number of rounds at McIntyre. But on Nov. 20, 2018, Sacramento County District Attorney Anne Marie Schubert concluded that the shooting was lawful.

“This department has had several opportunities to be heroes to community members in need,” BLM Sacramento wrote in its letter to Jones, “instead your officers chose violence first when those community members were black.” In his response, Jones refused to provide the names of officers involved in incidents that BLM Sacramento cited and criticized Faison, its leader, personally. “I wanted to extend you the courtesy to let you know that none of your demanded items will be forthcoming,” Jones wrote. “In my opinion, there are far more responsible, effective voices for the African American community here in Sacramento Ms. Faison; in fact there is nothing local law enforcement can do that will earn your approval.”

On Dec. 20, 2018, Burris filed his latest complaint against the department, alleging that when Davisha Mitchell, 27, was booked into the Sacramento County Main Jail on a domestic assault charge in 2017, deputies smashed her head into a wall, leaving her with a chipped tooth, bloody lip and mouth, and contusions on her body. “At the end of the day, you want more than just the resolution of an individual case,” Burris said, “but a sense on the part of the sheriff to look at the issues as an opportunity for reforms.”

Jones and a spokesperson for the sheriff’s department did not respond to multiple interview requests for this article.

“I can’t breathe. I’m dead.”

Marshall Miles’s family moved to Sacramento from Oakland in 1992. Andrews and other family members described Miles as an “average kid” who enjoyed sports, but struggled in school.

“He was always playing outside, making up some kind of game with some balls and sticks, or whatever,” Maureen Miles said of her younger brother. “We thought he was going to the NBA.”

More than a decade ago, Miles got married; he and his wife have a 4-year-old son. Miles also has a 15-year-old daughter.

His pro basketball dreams were dashed by his troubles with the law, according to his sister. Miles was arrested constantly, mostly for nonviolent drug offenses, and family members say he was incarcerated around 2008 in a state penitentiary, spending seven years there. For a few years after that, he was locked up in the county jail on a parole violation.

But Miles’s family insists that nothing in his past resembled the behavior described by the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department the day of his October 2018 arrest, subsequent hospitalization, and death.

In the surveillance footage released publicly by the sheriff’s department in December, Miles is seen being placed in the back of a deputy’s squad car. According to a sheriff’s department statement, Miles was initially arrested by the California Highway Patrol officers; the agency’s footage was not included in the publicly released video.

“I can’t breathe, help me!” Miles said as the squad car door was closed. “Come on, man. This is uncalled for. Can I tell you what happened? Listen.”

“No,” the deputy responded. “I don’t have to listen.”

Seemingly short of breath, Miles tried to alert the deputy to people passing by at the Power Market who he believed were seeking to harm him.

From the in-car camera angle, it’s unclear if the people were actually on the scene.

“They’re suffocating me right now, y’all,” he said. “I feel the oxygen going out of my mouth.”

Upon arrival at the main county jail, Miles repeatedly shouted that someone—presumably a sheriff’s deputy—was going to kill him. Footage shows several deputies moving Miles from what appears to be the jail garage to a prisoner processing area.

“If you relax and stop acting silly—” one deputy said.

“I can’t breathe,” Miles replied. “I’m dead. I’m dead.”

“You’re not dead,” another deputy replied. “You’re talking.”

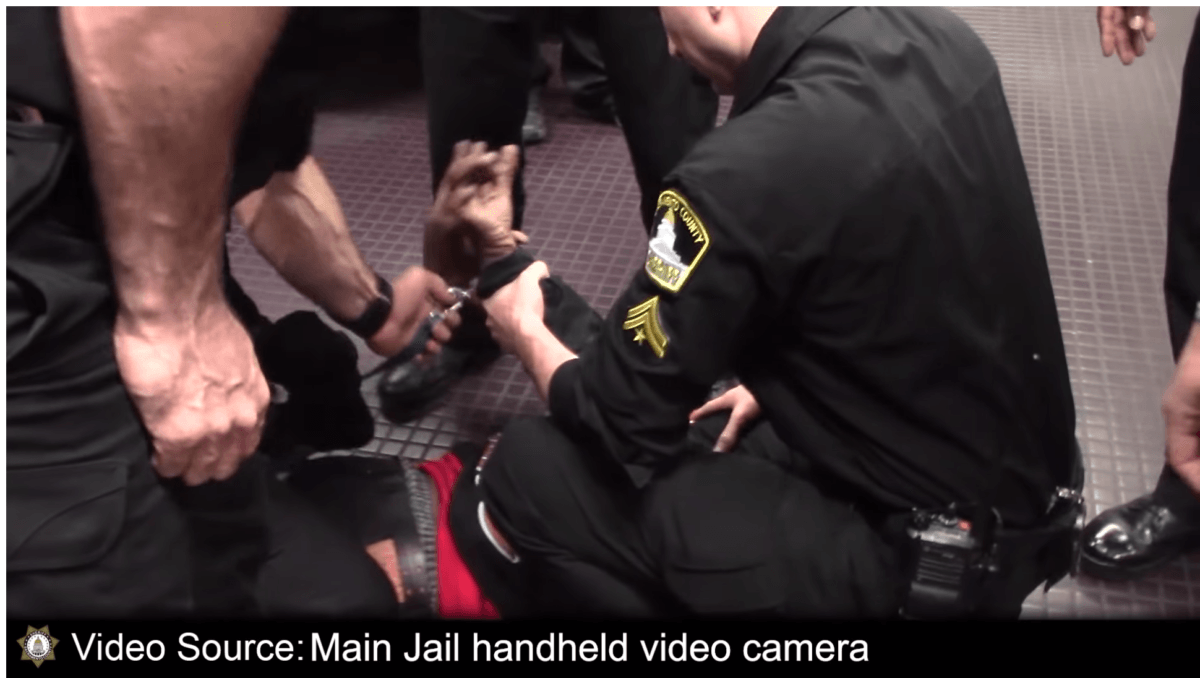

At least seven deputies held Miles down on a concrete garage floor, while his ankles and wrists were tied together with a blue strap. A nurse later appeared in video captured on a handheld camera, presumably checking for vital signs.

But after Miles was moved to the floor of a cell marked with the word “Segregation,” he stopped responding to deputies’ instructions. His belt had been removed and his jeans rested halfway down his legs, exposing his underwear. His socks and shoes had also been removed.

“Marshall! Marshall! You’re not going to move until the door is closed,” a deputy said as restraints were removed.

Once it was clear that Miles wasn’t moving, deputies re-entered the cell with a nurse and called for an ambulance. CPR was administered, and a defibrillator was used to no avail.

“He suffocated, and he told them he could not breathe, so many times,” Andrews said. She did not watch the full video, but her eldest daughter had described it to her.

“They just don’t know what they did to our family. They destroyed my life. It’s just not the same,” Andrews said through tears.

Andrews said Miles struggled with depression and other mental health issues. “I had concerns about his mental health, because his dad had mental issues,” she said. “My son was dealing with something that he wouldn’t talk about and he needed to have some type of help.”

For years, mental health advocates have linked lack of training to the number of people shot and killed by police officers. There are more than 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S., but just 3,000 of them require their officers to undergo crisis intervention training, which includes learning de-escalation techniques and the signs of mental illness. And academics and advocates alike argue that law enforcement is fundamentally unsuited for the job of responding to mental health crises.

In the video released by the sheriff’s department, Sgt. Shaun Hampton describes Miles’s behavior as “erratic,” and says, “Miles can be observed talking rapidly and making statements, which did not make any sense, and exhibiting several signs of narcotics intoxication.”

Even as they transported an unresponsive Miles to a nearby hospital, authorities filed paperwork to charge him with two counts of misdemeanor vandalism, for damage to vehicles near the Power Market. The Sacramento Bee initially reported that Miles’s arrest was on suspicion of felony crimes.

Doctors told family members that Miles had suffered a massive heart attack. A preliminary toxicology report showed Miles had methamphetamine, cocaine, Ecstasy, and marijuana in his system during the incident, according to investigators who spoke to KOVR, the local CBS affiliate. An autopsy noting an official cause of death, however, has not been released by the county coroner.

Police shooting thrusts Sacramento into the national spotlight

The March 2018 shooting death of Stephon Clark, an unarmed 22-year-old Black man killed by Sacramento police officers in his grandparents’ backyard, thrust Sacramento law enforcement into the national spotlight and ignited protests across the country. Local activists say that attention in turn spurred calls for more transparency in the county’s law enforcement, which had seemed hopeless under the decades-old California Peace Officers Bill of Rights, which heavily restricts public access to law enforcement disciplinary records and civilian complaints. Campaign contributions to Sacramento DA Schubert, who was re-elected in June, were also scrutinized; the Sacramento Bee reported that she received $13,000 from two local law enforcement unions in the days after Clark’s killing.

In October, the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors rejected an appeal by Jones to strip the inspector general of broad powers to investigate officer-involved shootings and other complaints against his department. Community members said Jones’s move was a reaction to Inspector General Rick Braziel’s report calling the 2017 shooting of Mikel McIntyre excessive and unnecessary. Jones locked Braziel out of his own office in the department after the August 2018 release of the report.

In December 2018, the Board of Supervisors sought legal counsel regarding a plan from Jones to narrow the inspector general’s mandate.

On Jan. 1, a new state law took effect that makes public the details about internal investigations into officer-involved shootings, sexual assault allegations against officers, and cases of officers caught lying while on duty. In December, a union representing sheriff’s deputies in San Bernardino County sued unsuccessfully to stop the regulations. Last week, The Sacramento Bee and The Los Angeles Times sued The Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department, alleging that the department refuses to follow the new law.

Marshall Miles’s still-grieving family hopes that the inspector general will one day give answers about his death that the sheriff’s department has yet to provide.

“It seems like things are getting worse,” Maureen Miles said. “It’s sad to say, but my brother isn’t the last. It’s just a matter of time.”