Hundreds Stuck in California Prisons as Prosecutors Seek to Block New Law

Senate Bill 1437 virtually eliminated the ‘felony-murder rule,’ but district attorneys aren’t ready to let it go.

One April night in 1994, 18-year-old Michael Tirpak picked up his friend, 17-year old Darrell, and two other teens who were brothers, Juan and Alex. They went to a party, but were asked to leave when Juan, 16, who was high on PCP, became disruptive. Tirpak planned to drop Juan and Alex at home before returning to the party.

On the way to their house, Tirpak pulled the car over and ran to a pay phone down the block. While he was on a call, Juan “went crazy,” according to his brother Alex, pulled out a gun, and, in the course of an attempted robbery, shot a man coming out of a nearby liquor store. Tirpak, who later said he sensed something was wrong but was unsure of what had happened, returned to the car, and Juan waved the gun at everyone. “Take me straight home now [or] I’ll shoot everybody in this fucking car,” Juan said, according to court documents.

All four teens were arrested and indicted, but only Tirpak’s case went to trial, where he was found guilty of aiding and abetting a felony murder despite his limited involvement.

Although prosecutors argued that Tirpak helped look for a target, he has consistently denied that, saying he was unaware of Juan’s intentions. The trial court found that he did not know anyone had been shot, never handled the weapon, approached the victim, or did anything directly associated with the crime. His conviction was based in part on the testimony of Juan, who pointed the finger at Tirpak to deflect blame from himself. Alex pleaded guilty and later, in a motion for a new trial, testified that Tirpak “never knew what was going on.

Tirpak was sentenced to life without parole because the jury made a “special circumstance finding,” meaning it found evidence the murder happened in the course of a robbery where at least one defendant was armed. The other teens all took plea offers and have been out of custody for years.

In 2015, Tirpak was resentenced to 25 years to life after the Loyola Project for the Innocent took on his case. Even District Attorney Jackie Lacey agreed in a written brief that Tirpak “did not demonstrate reckless indifference to human life” and was entitled to resentencing.

And last year brought an even more promising development for Tirpak. California lawmakers passed Senate Bill 1437, which effectively eliminated the so-called felony-murder rule that was used to convict Tirpak of murder. Under this doctrine, criminal defendants could be held responsible for the deaths of victims that occurred in the course of another crime, usually robbery, even if that particular defendant didn’t participate in the actual killing or was unarmed.

Critics had argued for years that the doctrine gave prosecutors a powerful bargaining chip to persuade defendants to agree to plea bargains, even when, as in Tirpak’s case, they may have been auxiliary to the crime with no intent to do harm. The new legislation, which went into effect in January, was specifically intended to be retroactive, meaning people convicted under a felony-murder theory could apply for resentencing.

Given Lacey’s earlier support for Tirpak’s resentencing, his lawyers had hoped she would support Tirpak’s motion for release. But Lacey opposed it. Her office argued in a brief that SB 1437 was unconstitutional because it “violates the separation of powers” by allowing the legislature to reopen cases already decided by the courts and giving courts pardoning power meant to be held only by the governor.” (Lacey’s office did not respond to a request for comment.)

Any time a DA in a particular county resists the Legislature, I think it does call into question their role in our system.

Kate Chatfield Re:store Justice

She’s not alone in her opposition. District attorneys across the state sought to influence the Legislature through the California District Attorneys Association and now that the law has passed, they are filing court motions arguing that it is unconstitutional. In at least one county, Orange, the constitutional challenge was granted by the trial court, meaning that it will move to the appellate courts and possibly the California Supreme Court. This could delay the resentencing process by months or years for many of the hundreds of prisoners waiting to file their motions.

Why would a prosecutor, whose job is to enforce the law, stand in the way of approved legislation? Advocates say the fight over SB 1437 shows the power DAs have in the political process and the ways they can wield it, both by opposing legislation and by clogging the courts with lawsuits and motions that serve to delay reform.

“Any time a DA in a particular county resists the Legislature, I think it does call into question their role in our system,” said Kate Chatfield, an attorney with Re:store Justice, a group advocating reform of California’s criminal laws, who also teaches at the University of San Francisco Law School. “It definitely slows the process down.” And some of those people, like Tirpak, have waited more than two decades for this change.

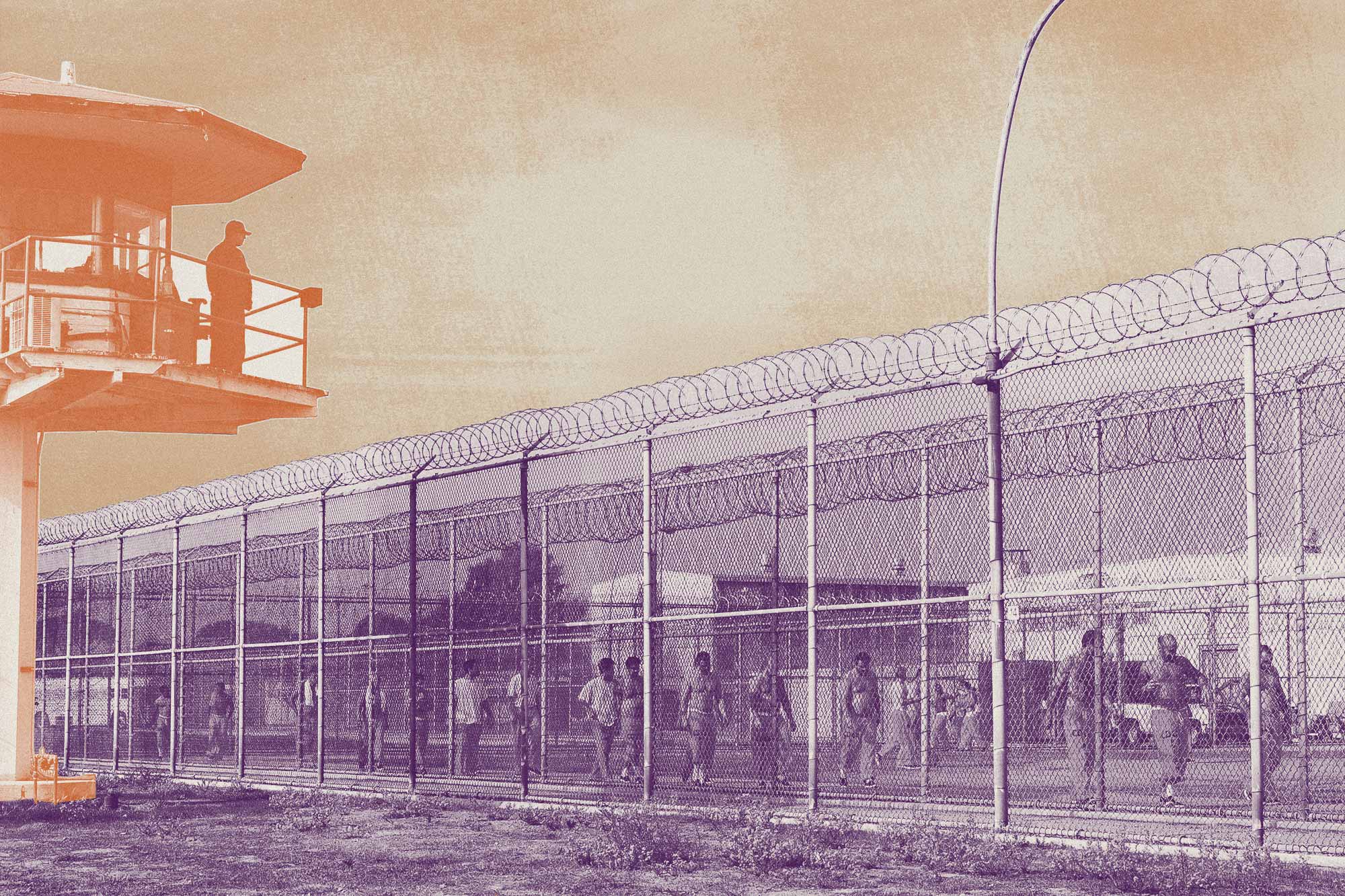

The felony-murder rule has long been under scrutiny as courts reassessed the impact of harsh criminal sentencing laws that became popular in the 1980s and ’90s. Those policies, such as California’s three-strikes law, led directly to the overcrowding of prisons and to conditions so unconstitutional that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2011 that the state had to reduce its prison population.

Since then, California has slowly been unwinding some of the harsher sentencing laws with great success. A 2018 report from The Sentencing Project found that California had successfully decreased its prison population while retaining historically low crime figures.

SB 1437 amended California’s felony-murder rule to eliminate its use in most cases where someone with no intent to kill is charged with murder. Prosecutors must now prove malice to charge these people with murder.

Yet district attorneys are still working to block the law. Forty-two district attorneys from across the state signed a Sept. 2, 2018 letter to then-Governor Jerry Brown objecting to the new law, arguing that it “goes too far” and “will allow everyone convicted of murder … to petition to have their convictions vacated.”

It was not just DAs from the typically Republican-leaning Central Valley who opposed reform. Elected prosecutors such as Nancy O’Malley in Alameda County and Jeff Rosen in San Jose also opposed the law, even though both prosecutors have called themselves reformers.

Lacey opposed SB 1437 from the beginning and told a local TV news anchor that “at least half of” the people resentenced under the change would be “part of a violent street gang.” She also opposed last years’ bail reform legislation (although says she supports bail reform generally) and was against Proposition 47, a voter initiative that reduced some felonies to misdemeanors.

Lacey defended her stance on SB 1437 in a letter to the Los Angeles Times, writing, “I support criminal justice reform that does not jeopardize our safety.”

District attorneys in California have tried to block change before. In 2016, Prop 57 was on the ballot for the general election. Proposed by then-Gov. Jerry Brown, it would allow all people convicted of nonviolent felonies to seek parole after serving their minimum sentences and require transfer hearings before juveniles could be tried as adults. The California District Attorneys Association filed a lawsuit to oppose it. Despite the attempt to remove Prop 57 from the ballot, it passed decisively with 60 percent of the vote.

Now, the association opposes a law that extends Prop 57 by preventing the prosecution of 14- and 15-year-olds in adult court.

“Some prosecutors have manufactured a controversy by challenging, rather than enforcing, the law,” wrote Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. “They’re substituting their own policy preferences—and the preservation of their own power—for the democratic process. It’s a cynical move with no legal basis.” Prosecutors continue to formally oppose the measure in court and advocate against it.

When it comes to SB 1437, fewer than a dozen petitions for resentencing have been heard statewide, and the vast majority have been granted. As in a criminal trial or parole hearing, prosecutors represent the state and provide their version of the alleged crime and weigh in on the petitioner’s suitability for release. (In SB 1437 hearings, the burden is on the prosecutors to prove that the defendants had intent to kill.)

Some prosecutors have manufactured a controversy by challenging, rather than enforcing, the law.

Erwin Chemerinsky University of California, Berkeley, School of Law

In some cases, district attorneys have supported the petitions, on the grounds that it’s both fair and fiscally wise to support the petitions and release prisoners who in many cases have already served decades. Some DAs have opted to oppose almost all petitions, but it’s not always clear why California prosecutors are supporting certain petitions but not others.

Take the case of Tara Williams, who served almost 25 years in prison. In 1993, Williams was the driver when two friends went inside a liquor store and shot the owner in the course of a robbery. (The theft netted only $6 and food stamps.)

Williams was charged with murder under the felony-murder rule and sentenced to life in prison without parole. (The actual shooter took a plea and was released after about three years.) Williams was granted release through an SB 1437 petition, which was not opposed by Lacey, and left prison in February.

It remains to be seen how prosecutors and judges will deal with these cases. A case in San Diego County, where District Attorney Summer Stephan has opposed SB 1437, may set the tone for a coming battle in the California Supreme Court.

In April 2014, Kurese Bell, then 17, went with his older friend Marlon Thomas to rob two marijuana dispensaries in San Diego. During the second robbery, an armed security guard surprised the pair. A gunfight ensued and ended with Thomas’s death at the hands of the guard. Bell was charged with first-degree murder as an adult for his part in the crime that led to his friend’s death.

The San Diego DA’s office, then under the direction of Bonnie Dumanis, took a hard line in the case. She used a little-known 50-year-old legal doctrine called the “provocative act” theory to charge Bell with his friend’s death.

Under this theory, Bell was held responsible for murder, and he faced multiple life sentences. Stacked with gang and gun enhancements allowed under California law, Bell was sentenced to a 65-years-to-life term. Even though Bell was a juvenile at the time of the crime and arguably could have been tried in juvenile court, Stephan’s office vigorously opposed a juvenile sentence.

But now, Bell may have a second chance under SB 1437, which allowed his attorneys to argue that he did not actively participate in the events leading to his friend’s death (even if he may have participated in the robbery scheme).

Advocates say the DAs are out of step with their communities, which overwhelmingly support reform.

Stephan’s office has not responded to Bell’s motion. If she invokes the same constitutional challenge that DAs in Los Angeles and Orange County have filed, Bell’s case may also need to wait for the state Supreme Court to settle the controversy.

Advocates say the DAs are out of step with their communities, which overwhelmingly support reform. Lacey has been a particular disappointment to reformers.

“There is finally widespread support across the political spectrum for changing the criminal-justice system in meaningful ways,” Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors wrote in a recent L.A. Times op-ed. “Now we just need key public officials, including Lacey, to get on board.”

Lacey ultimately conceded that Michael Tirpak was entitled to relief. This year, a Los Angeles judge denied Lacey’s constitutional challenge to SB 1437, forcing Lacey’s office to stand by its prior statement that Tirpak was not responsible for the murder. Tirpak was finally released in February 2019 after serving 25 years in prison.

Correction: This story has been corrected to note that the law that would extend Prop 57 does not include carve outs for murder or other offenses.