How Jails Are Replacing Visits With Video

Two sheriffs in Missouri have cut off all in-person visitation in favor of costly video technology.

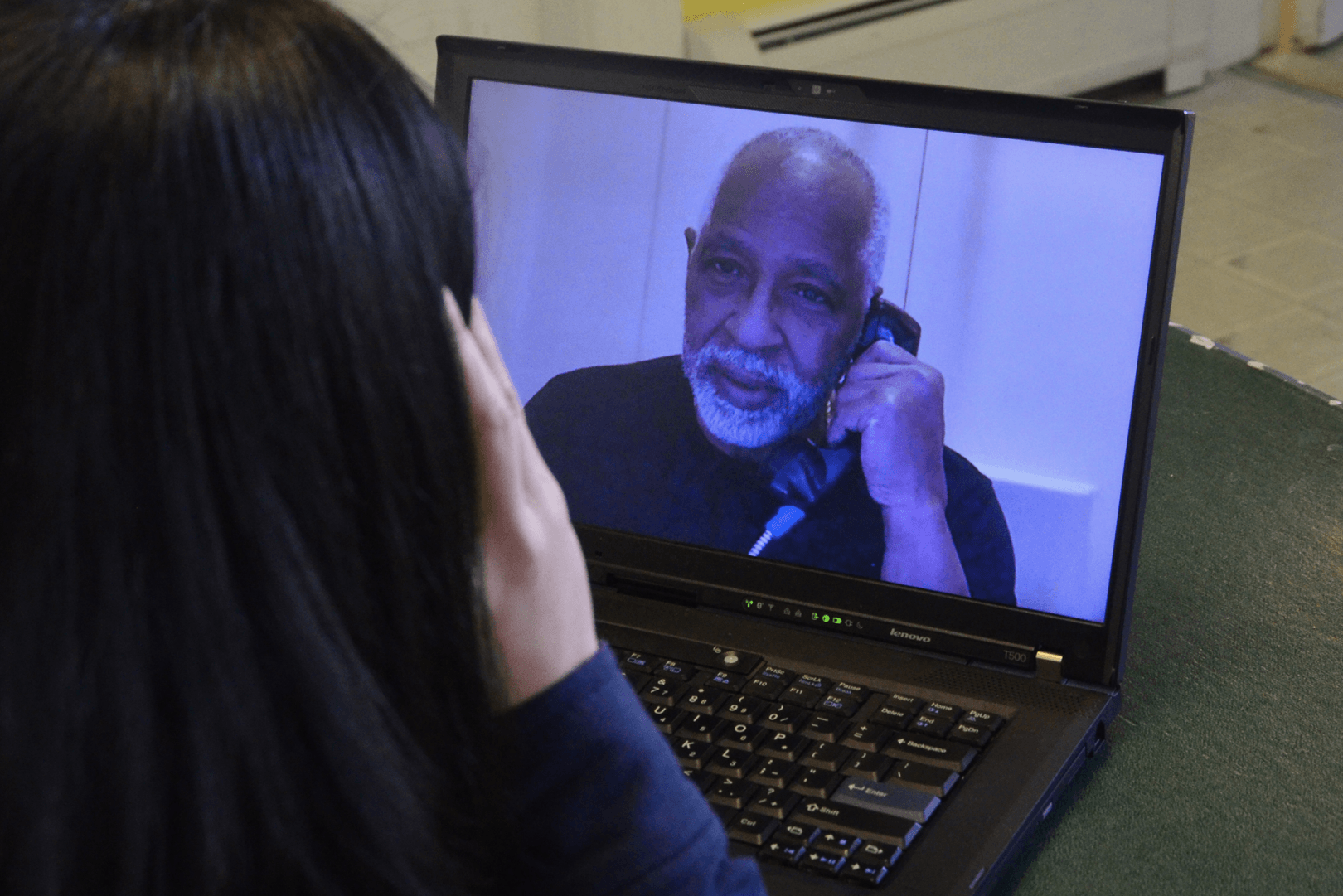

For decades, friends and relatives of incarcerated people have traveled to jails to communicate with their loved ones face-to-face through a glass barrier.

But increasingly, jails across the nation are cutting off these visits. Instead, all communication must take place through a digital screen. On March 18, the Newton County Sheriff’s Office in Missouri announced that, effective immediately, no in-person visits would be permitted. Visitors to the jail would use a video portal in the same area where visitations had always taken place. But the person they came to see would remain in the jail common spaces at a different video portal. Incarcerated people could still meet with one person face-to-face: their attorney.

The move follows a similar decision in nearby Greene County, which encompasses Springfield. James Craigmyle, public information officer for the Greene County Sheriff’s Department, told the Joplin Globe that replacing visits with video creates a safer environment because officers do not have to transfer prisoners to and from the visiting area.

Chris Jennings, Newton County’s sheriff, said that because the jail has to devote fewer resources to such monitoring, it has expanded visitation from three days a week to five.

Newton County’s video platform, called CIDNET, is provided by Encartele, a private company that specializes in prison telecommunications. Although video calls that visitors make inside the jail are free, calls made from outside are not. Video calling from home in Newton County costs 40 cents a minute—more than the 31 cent fee for phone calls. The platform also offers instant messaging for 10 cents a minute.

The option of video calls from home can be financially beneficial for families and friends. In-person visiting is often expensive and onerous—sometimes prohibitively so. Visitors must factor in the costs of lost wages, childcare, food, accomodation, and other travel-related expenses.

But the technology is increasingly used as a justification to eliminate in-person visits. According to a 2015 report, 74 percent of jails that adopted video visitation subsequently banned in-person visits.

Video calling from home in Newton County costs 40 cents a minute—more than the 31 cent fee for phone calls. The platform also offers instant messaging for 10 cents a minute.

Wanda Bertram, a communications strategist at the Prison Policy Initiative, estimates that over 600 jails across the nation have implemented the technology, though not all of them have banned in-person visits. A Department of Justice study noted that state prisons have been slower to adapt to video visits due to the challenges of implementing a new technology in a statewide system.

“It’s very different to talk to somebody through a screen than in person, to be able to see their face and hear their voice,” said Bertram.

Video visits are a noticeably poor substitute. In a 2015 Prison Policy Initiative survey, families complained about the quality of the calls—freezing video, audio lags, and pixelated screens—as well as a lack of privacy during video visitations, as prisoners usually call in from portals placed in the jail’s common areas. A writer for Ars Technica who decided to try the remote service for Knox County Jail in Tennessee was unimpressed. He found that “the call cost 19 cents per minute and was noticeably worse than a FaceTime or Skype call. It was grainy and jerky, periodically freezing up altogether.”

For jails, the impetus for replacing in-person visitation with video sometimes comes down to money: The facility can cut down on labor costs and get better deals from technology companies.

The technology industry has begun to integrate itself into the carceral system through equipment and software sales, IT support, and phone-and-video revenue sharing contracts. In Newton County, Encartele provides the equipment, installation, and maintenance at no cost to the county. Both the company and the jail get revenue from fees incurred by people using the system from home. In February, Encartele also announced a partnership to eventually incorporate facial recognition technology into the video platform.

Lawmakers across the country have started recognizing the problems with video visits. In 2015, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser required the local Department of Corrections to reinstate face-to-face visits at the D.C. Central Detention Facility. In 2017, California’s Board of State and Community Corrections voted to require all new jails to have in-person visitation, though the mandate was not retroactive for jails that already had different policies or for those under construction while the rule was passed. That same year, U.S. Senator Tammy Duckworth introduced the Video Visitation and Inmate Calling in Prisons Act, which would require the Federal Communications Commission to regulate video and phone calls in correctional facilities and mandate the existence of in-person visitation.

Visitation of any sort matters: It helps incarcerated people and those who love them by preserving and even strengthening social ties. A survey by the Vera Institute of Justice found that prisoners who regularly used video chatting services had a 40 percent increase in in-person visits, suggesting that greater access in communication forged stronger bonds. A study from the Minnesota Department of Corrections found that visitation significantly decreases the risk of recidivism.

Bertram believes cutting costs by sacrificing visits will do more harm than good in the long run. “If jails are trying to make an investment,” she said, “they should invest in retaining those visits.”