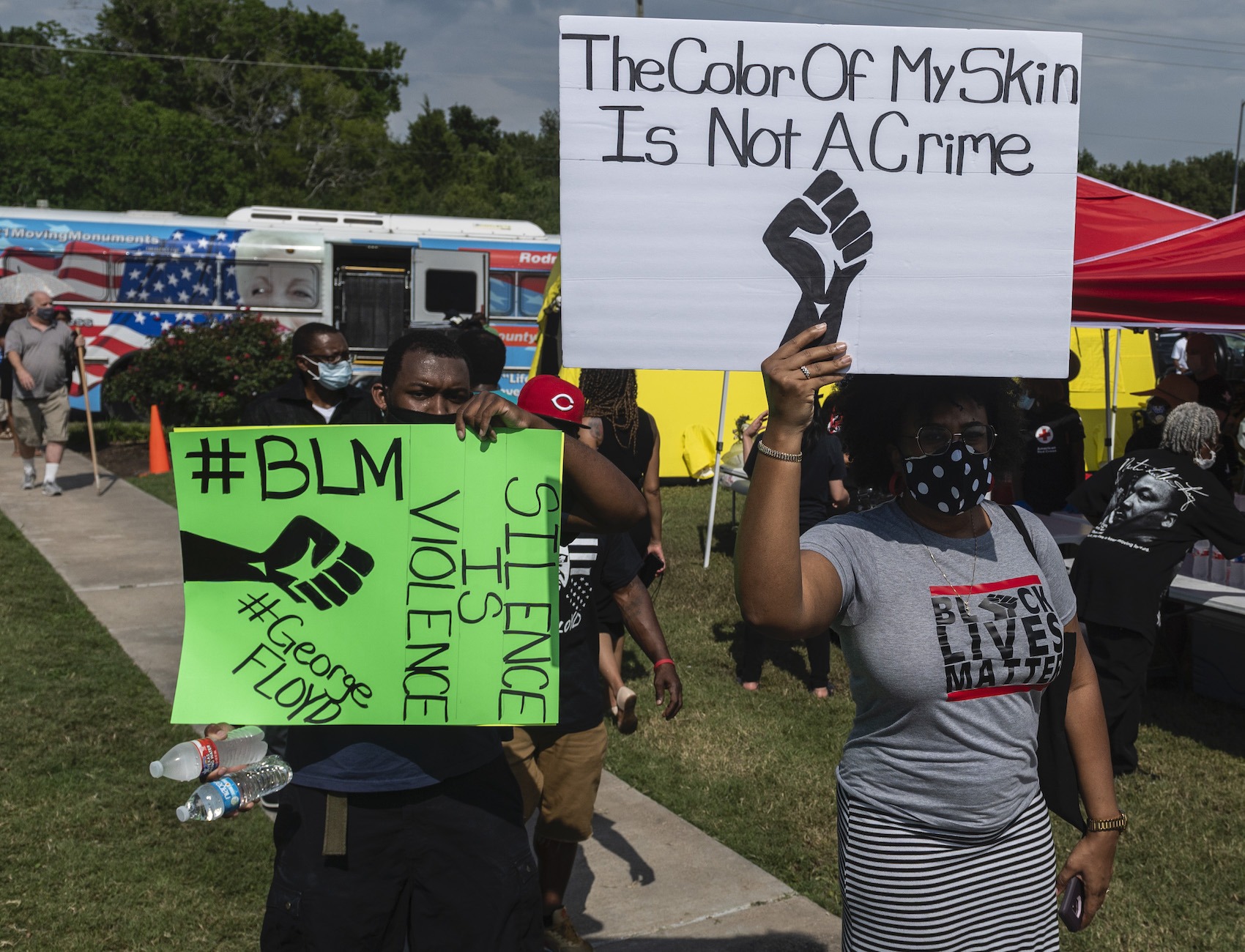

Houston’s Drug Busts Have a Clear Target: People of Color

Two years’ worth of data shows how disproportionately the city’s police and prosecutors target certain neighborhoods.

On Feb. 8, the Houston Police Department (HPD) arrested a homeless man, 57-year-old Israel Iglesias, for allegedly handing an undercover cop 0.6 grams of methamphetamine. Iglesias died the next day in the county jail. Results of his autopsy remain pending.

Iglesias’s death has raised obvious questions about what priorities the police and the Harris County prosecutor’s office have when it comes to solving or preventing crimes: Why, critics have asked, did police find it necessary to execute an undercover drug sting in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic? Why did they choose to target homeless residents? And why did District Attorney Kim Ogg’s office believe this was a case worth charging?

Data from the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, a civil rights nonprofit, helps shed some light. According to the organization’s record of criminal case dispositions between Jan. 29, 2019, and Jan. 28, 2021, the Harris County district attorney’s office charged at least 270 people with “manufacture or delivery of less than one gram” of a “Penalty Group 1” drug—which in Texas includes cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, and ketamine. Of that number, 218, or more than 80 percent, were Black people. Only 20 percent of residents in Harris County identify as Black. (The data set doesn’t include cases that are pending in the court or those that may have been sent to pre-filing diversion programs. Nor does the data categorize race beyond Black or white, suggesting the percentage of non-Hispanic white defendants is even lower than the data states.) Of the 270 people charged, 44 were listed as either homeless or having no set address.

The data shows that Ogg’s office did temporarily stop filing Penalty Group 1 charges between April 30 and Oct. 15, 2020. Those charges have since resumed. Between January 2019 and 2021, Ogg’s office charged thousands of people for simple possession of less than 1 gram of a Group 1 controlled substance.

Of the 270 cases filed, 245 stemmed from Houston Police Department arrests. The other cases originate with the Harris County Sheriff’s Office, the Texas Department of Public Safety, and other offices. Charges for other, more serious tiers of drug delivery were also racially skewed, according to the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition’s data. Neither Ogg’s office nor the police department immediately responded to requests for comment.

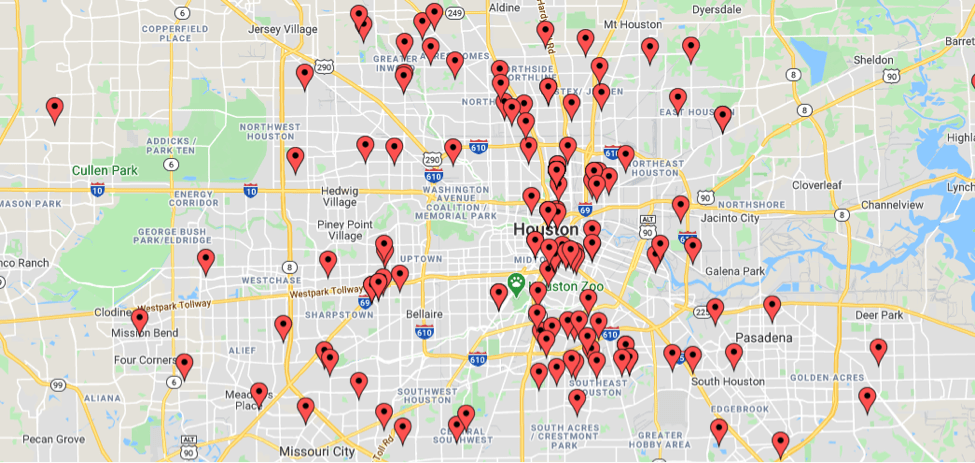

A visualization of the available home addresses of those charged for alleged delivery of Group 1 drugs in Houston shows that they were heavily concentrated in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods—especially downtown.

Jay Jenkins, the Harris County project attorney for the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, told The Appeal that the data shows Houston Police and Harris County prosecutors need to take a serious look at the communities they choose to target.

“In an overwhelming majority of cases, manufacturers or dealers of drugs are arrested based on possessing a large quantity of that drug—but the manufacture or delivery of small amounts of drugs requires either police surveillance or an actual police operation of an undercover buy,” Jenkins said. “So when you look at how the patterns shake out for these charges, you see they are overwhelmingly African American and they are overwhelmingly coming from African American ZIP codes, which tells us a lot about how the city of Houston is being policed and where officers are being sent.”

Low-level drug stings are sometimes referred to as “police created” crimes. In September, Katie Tinto, a professor at University of California, Irvine, wrote in USA Today that American police often “create elaborate schemes using significant public resources to tempt individuals who posed no public safety threat prior to the operation. And these examples reveal another tactic in the undercover sting playbook: targeting the most vulnerable and ‘temptable’ people, like students with special needs, individuals experiencing homelessness, and those who are in desperate need of money.”

The data recorded by the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition begins on the day of a 2019 raid. On Jan. 29, Houston police raided a home at 7815 Harding St. after officers Gerald Goines and Steven Bryant alleged that an informant had bought heroin from the couple who lived there—Dennis Tuttle, 59, and Rhogena Nicholas, 58. During the raid, officers killed Tuttle, Nicholas, and their dog, but did not recover any heroin. The families of the victims maintain that neither person ever sold drugs.

Goines, who signed the warrant for the raid later admitted that he’d lied and that there was no informant. Goines, Bryant, and four other officers were charged with crimes related to the raid.

Harris County prosecutors have since reviewed thousands of Goines and Bryant’s cases. In July, Houston police released an audit of the cases, revealing that there were errors and inconsistencies in many of Goines and Bryant’s cases. The report also issued recommendations for a revised standard operating procedure and more oversight for the narcotics division.

This month, Chief Art Acevedo announced that, after about five years, he will be leaving to lead the Miami Police Department. Miami Mayor Francis Suarez called him the “Tom Brady or Michael Jordan of police chiefs.” However, Acevedo’s record in Houston does not match the rhetoric. During a news conference the day after Acevedo announced his departure, he issued a dark prediction for Houston: “Get ready for 500 murders.”