A Mother Grapples With an Adoption that Led to Deaths

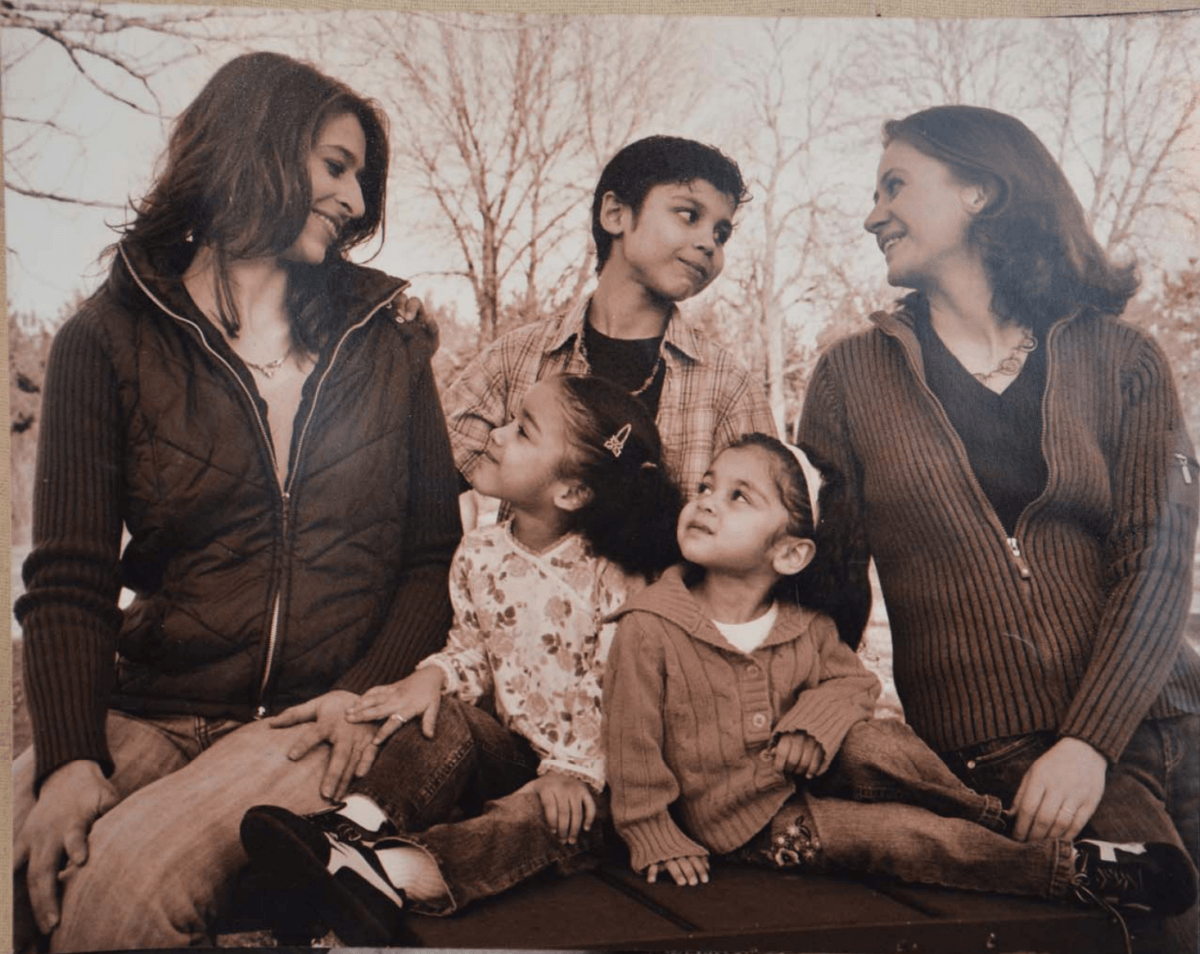

Tammy Scheurich, who lost three biological children in the Hart family crash last year, tells her story for the first time.

It’s been nearly a year since Jennifer Hart drove her family, including at least five of her six adopted children, off a cliff to their deaths on the rocky shores of Mendocino County, California.

But for Tammy Scheurich, the pain is still fresh. Scheurich, the biological mother of Markis, Hannah, and Abigail Hart, learned about their deaths in October, more than six months after it happened. “Those are my children,” she said by phone the day after she heard the news. “This was not supposed to happen.”

Scheurich learned that Markis and Abigail had been found dead at the bottom of that cliff, and that Hannah was still missing, only after The Appeal contacted her stepmother in October. Her family name was in a passel of records released by the Clark County sheriff’s office in Washington in September, which led the reporter to her stepmother on Facebook. Despite having access to those records themselves, no law enforcement agencies involved in the investigation contacted Scheurich, though the Mendocino County sheriff’s office put a call out through the media asking relatives to come forward.

Scheurich and her family didn’t see those calls, or read any news reports about what had happened until October, when Scheurich pored over every story she could find. She hadn’t seen her kids in nearly 15 years, but now she saw photos them alongside descriptions of their long-term abuse at the hands of their adoptive mothers.

“I’m devastated, the news I’ve been reading and everything—it’s crushing to me,” Scheurich said at the time. “I’m trying to process all of this and trying to still live my life.”

Scheurich relinquished her rights to her children in 2004 after being charged with medical neglect. Many other cases in the child welfare system look like hers: Young mothers who are ill-equipped to care for their children, living in poverty without the necessary support. Child Protective Services (CPS) makes a finding of neglect, and ultimately, many of these mothers lose their children forever.

And if something happens to these children after the parents’ rights have been terminated, it’s likely they will never know.

The story of how Tammy Scheurich lost her children is filled with near misses and problems that compounded each other. She said she was homeless on and off since she was 17, when she ran away from home to meet a much older boyfriend. She took a Greyhound bus from Corpus Christi, Texas, where she was living with her grandparents at the time, to meet him in Houston, but he never showed up. Her grandfather told her, “You make your bed, you lie in it,” and refused to let her come back home.

“That was my lesson and that’s how I became homeless,” Scheurich recalled. “I lived inside the Greyhound bus station for like a month.”

After being taken from her mother’s custody as a toddler, she spent most of her childhood living with her father’s parents, but she had a difficult relationship with her dad, who remarried and had two more children. When Scheurich was 13, she says she threatened suicide, and was sent to the San Antonio State Hospital, the first of three stays there for a total of nearly eight months resulting from threatened or attempted suicide, according to Scheurich’s own account. She has since been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and major depression, she said, and is receiving disability benefits each month.

Scheurich spent much of her adult life bouncing around from Corpus Christi, where her dad and stepmother lived, to Columbus, Texas, where her grandparents settled, to Houston, where she was intermittently homeless. She says she never developed a drug habit, like many of her peers on the street, and she always felt accepted. “The streets have been one of those places that I always kind of turn to, because the people out there don’t look down on you,” she said. “It’s almost like a family, if you think of it like that, and you don’t get judged. Everyone has a story.”

Scheurich was 18 when she had Markis, and left him for long stretches with her grandparents. But she was older, and calmer, she said, when Hannah was born three and a half years later.

Things had calmed down so much and I could see light at the end of the tunnel.

Tammy Scheurich mother of Markis, Hannah and Abigail

She was pregnant with Abigail and living with Markis and Hannah in Corpus Christi when a series of events led to her entanglement with CPS. At a birthday party in July 2003, Hannah, then 1 and a half, got covered with ant bites, one of which got infected with a hard-to-treat staph infection, Scheurich said. “They had to remove a chunk the size of a quarter, and that deep, of the flesh around there, and gave her IV antibiotics,” Scheurich remembers.

A doctor informed CPS, which opened a case for potential medical neglect. When the agency got involved with her family, Scheurich said she was scared, and briefly decided to place Abigail, who was not yet born, for adoption. “I remember having an ultrasound and not wanting to look at the screen,” she recounted.

But once they settled down in Columbus with her grandparents, Scheurich reconsidered. “Things had calmed down so much and I could see light at the end of the tunnel, and I thought, ‘Yes, I could do this.’” Abigail was born just after Christmas, but less than two months later, Scheurich would lose custody of her children for good.

It was February 2004, and the air in Columbus, Texas, was cool and damp, even as flowers were starting to bloom. It was just weeks before Hannah’s second birthday, and she had an upper respiratory infection that had turned into pneumonia.

Scheurich said she had taken Hannah to the doctor Feb. 9, and the doctor had changed Hannah’s asthma medications and sent them home. But according to a police report filed the next month, Scheurich did not show for a planned doctor’s appointment the next day and waited too long to take Hannah to a hospital, as instructed by a doctor over the phone. Scheurich maintains that she called an ambulance, but had no one to care for Abigail and Markis so she was forced to wait for a ride.

That ride was CPS worker Sharon Kearbey, who Scheurich thinks might have been summoned by the ambulance dispatcher. “Sharon was standing there in my living room,” Scheurich recalled. “She reassured me she wasn’t taking the kids away and that CPS was there to help in other ways.”

At the hospital, Scheurich remembers a nurse coming in to ask to talk to Kearbey. When Kearbey came back into the room, she told Scheurich that CPS was removing her children. “She already had the paperwork in her hand,” Scheurich said, crying.

Kearbey was contacted for this story, but she declined to be interviewed, citing her fear of being sued by CPS; she is no longer with the agency. She did say, by Facebook message, “I did everything I could for those kids, I loved them.”

After that day, Scheurich would never again have custody of her children. She voluntarily signed away her rights, expecting the kids would be placed with a foster family who wanted to adopt them in Missouri City, a suburb of Houston. But later she found out through CPS that the adoption fell through, and the kids were adopted out of state.

That would be the last she heard of them, until October 2018, 12 years after they were adopted by a Minnesota couple, Jennifer and Sarah Hart. She got a phone call from her estranged stepmother and learned her children were dead.

Colorado County charged Scheurich with child endangerment for the incident with Hannah. The indictment says that Scheurich did “intentionally, knowingly, recklessly, or with criminal negligence, engage in conduct, by omission, that placed Hannah Holliday-Scheurich, a child younger than 15 years of age, in imminent danger of death, bodily injury, or physical or mental impairment, by failing to seek medical treatment for her.”

She was originally given three years of “deferred adjudication,” which is similar to probation, but after she failed to pay the monthly court fees totaling $225, missed assigned community service, and failed to notify the court of a change in address, she was given 30 days in jail in April 2005. After she got out, she again failed to follow court orders, which included paying $1,266 in fees, and was sentenced to another six months in jail on December 19, 2006.

Scheurich said she was on a fixed income of just over $600 a month from her disability benefits at the time and couldn’t afford to pay the fees. “I just didn’t follow through with my probation stuff. … I’d go and report for my probation visits, but as far as paying anything, I didn’t pay anything,” Scheurich said. “I didn’t have the money to pay.”

She regrets not complying with the other mandates, but said she felt adrift without her children. Her court-appointed attorney, Louis Gimbert, did not return calls for comment.

When I signed my rights over, my right to know anything went away.

Tammy Scheurich mother of Markis, Hannah, and Abigail

Because Texas seals all its CPS and adoption records, it’s unclear why the Missouri City foster family fell through. Scheurich, who is white, was unable to recall their names but remembers them as a Black couple with three children of their own. She thought they would provide a good home for her children, who were biracial, and says they told her she would be able to stay in touch with her kids. “I had talked to the foster mom and had everything mapped out in my head, how it was going to be,” she said. “And it didn’t happen that way.”

When Scheurich learned that the Mendocino County sheriff’s office was looking for a DNA sample to match to remains that they thought could be Hannah’s body, she contacted the office to submit a DNA sample. A law enforcement officer was sent to her home to collect it.

When the results came in, a representative from the sheriff’s office sent Scheurich an email, time stamped at 9:40 a.m. Central Time, asking her to call them back to talk about the DNA results. Five hours later, before she had even checked her email, the Mendocino sheriff sent a press release, stamped at 12:26 p.m. Pacific Time, announcing a positive identification of Hannah’s remains based on Scheurich’s DNA sample, and confirming that Hannah was dead. “Why didn’t they call me?” she asked, angry and upset, when she heard the news. “When I signed my rights over, my right to know anything went away.”

As far as the law is concerned, the sheriff’s offices in Mendocino County and Clark County, Washington, which are investigating the case, did nothing wrong in failing to notify Scheurich—or Sherry Davis, the biological mom of the other three Hart children—of the deaths of their children. “I don’t know of any law that requires anything like that once your rights have been terminated to a child,” said Vivek Sankaran, a child welfare reform advocate and law professor at University of Michigan Law School.

He said he was in a similar situation last year with a client he was representing in her appeal of her parental termination case in the law clinic at University of Michigan. Her child, who had significant medical needs, died while in foster care. Sankaran learned this when the state’s attorney called to tell him that the appeal was moot. He had to tell his client and her family the news. “It was one of the worst moments of my career,” Sankaran said. “It was just really infuriating to me that nobody had picked up the phone and passed that information on in a more humane way.”

Sankaran sees the lack of such procedures as a byproduct of other dehumanizing court practices like not calling parents by their names (instead referring to them as “respondent” “mother,” or “defendant”) and not allowing them to speak at their own hearings. Judges and attorneys representing the state, he said, rarely consider the emotional impact of the life-altering decisions that happen in family court—both on the parents and the children themselves.

“The number one thing that bothers me about how we conduct business in foster care is that we’ve lost key concepts like humanity, dignity,” Sankaran said. “We’re prioritizing compliance and the needs of bureaucracy and accountability. ”

Suzanne Sellers lost the rights to her two children in 1999 and they were subsequently adopted. She’s now the executive director of Families Organizing for Child Welfare Justice, and her children got in touch with her when they turned 18.

Still, Sellers being out of contact with them for so many years posed challenges, like when her teenage daughter got her first Pap smear and wasn’t able to answer questions about her medical history because she didn’t know it. “Once adopted, the law says that … all of the rights and care transfers to the adopted parents and the mothers, the birth mothers, are expected to just disappear, just go away,” Sellers said. “And that’s very difficult to do, emotionally, spiritually, physically—we still do exist.”

Scheurich signed away her parental rights in the summer of 2004, convinced her children would stay in Missouri City.

Instead, in 2006, the children landed in the home of Jennifer and Sarah Hart, more than a thousand miles away in Minnesota. Two years later, Hannah, then 6, told authorities that her mother hit her with a belt. The women told police Hannah fell down the stairs, and no charges were filed. In 2010, Sarah Hart pleaded guilty to misdemeanor assault for leaving bruises on 6-year-old Abigail. And by 2018, they, along with their brother Markis and their adoptive siblings, were dead.

Of course, Scheurich didn’t know where they would end up when she had her goodbye outing with the kids at Houston’s Hermann Park the summer of 2004. They went to the zoo and saw the animals, before settling in the sun for a picnic.

“I talked with them. … Hannah didn’t understand and of course Abigail didn’t, she wasn’t even walking yet,” Scheurich said. “I talked to Markis and told him that I wouldn’t be seeing him anymore, and that I loved him, and one day I would be seeing him again.”