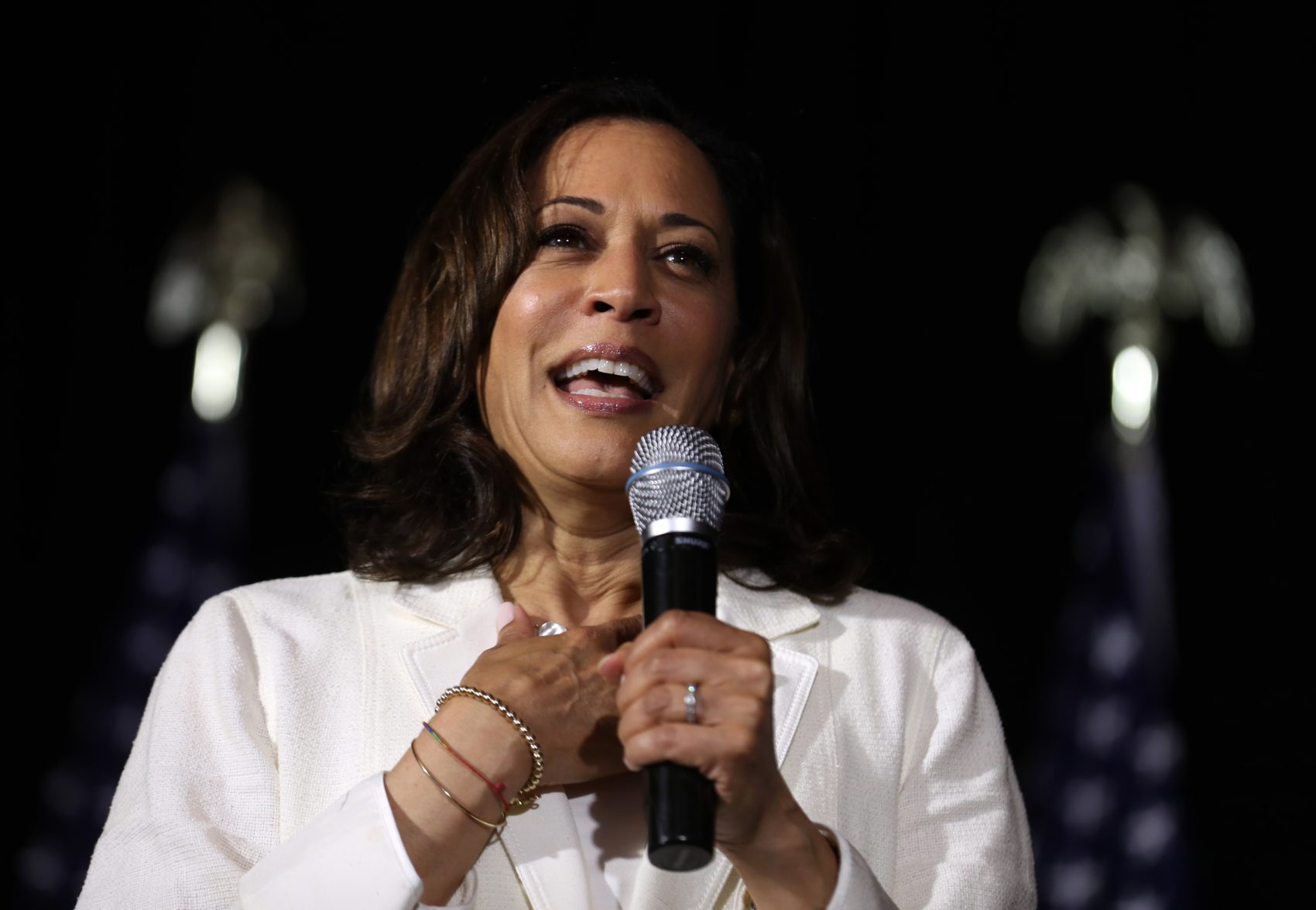

Harris’s Criminal Justice Plan Is More About Kamala Than Justice

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. Sometimes it seems as if U.S. Senator Kamala Harris thinks we aren’t paying attention. She seems to assume that if she chooses the right words, the ones […]

|

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. Sometimes it seems as if U.S. Senator Kamala Harris thinks we aren’t paying attention. She seems to assume that if she chooses the right words, the ones that are getting traction of late, that no one will notice how incongruous they are with the rest of her career. On Monday, the Democratic presidential candidate released a criminal justice plan, her version of a sweeping vision for what criminal justice in a Harris presidency could be. Like similar proposals put out by other candidates, Harris calls for an end to the death penalty, for more data collection, more alternatives to incarceration for certain offenses, and an end to cash bail. Her headline says that her plan will “transform the criminal justice system and re-envision public safety,” but her plan is less transformative than those released by her competitors, and it focuses less on re-envisioning public safety than it does on her own personal achievements and identity. Does she not know that her past and present identity as a tough prosecutor don’t help her make the case that she’s the candidate to help us out of mass incarceration? As district attorney of San Francisco and later as attorney general of California, Harris refused to help prevent prosecutors from withholding exculpatory evidence from defendants, she opposed DNA testing that could have cleared a death row prisoner whose conviction rested on shaky evidence, and sought to jail parents of truant children. As a candidate, Harris has touted her prosecutorial past, specifically promising to “prosecute the case against Donald Trump,” which, for some, has brought to mind chants of “lock her up!” against Hillary Clinton during the 2016 campaign. And more to the point, Harris makes no effort to address the fact that she is putting forward solutions to problems that she and other prosecutors caused. She is bullish in the politically safe territory of drug convictions, announcing, “It is past time to end the failed war on drugs,” adding, in italics, “and it begins with legalizing marijuana.” But it was Harris who laughed when asked in 2014 about marijuana legalization during her campaign to hold her seat as attorney general. Harris’s plan calls for supporting “proposals that de-emphasize criminal justice interventions in response to mental health issues because, until we have successfully strengthened our mental health care system, the criminal justice system will continue to be tasked with frontline interactions with people whose primary need is mental health care.” But as a district attorney, she brought a case against a mentally ill woman who had been shot by police. Cal Matters reports that San Francisco police broke down a “door inside a group home for mentally disabled people in 2008 and shot a 56-year-old resident,” but Harris didn’t charge the officers with a crime. “Instead she prosecuted the schizophrenic woman who was severely injured in the shooting.” The jury deadlocked, and ultimately the woman was able to collect damages. Even where her plan does not indicate any serious hypocrisy on her part, Harris stays in politically safe territory. She wants to stop transferring children to adult prisons, but does not suggest that they no longer be charged and tried as adults, and certainly doesn’t suggest that children don’t belong in cages at all. “Harris’s plan focuses on what political scientist Marie Gottschalk has described as the ‘non, non, nons’ of criminal punishment reform: non-serious, nonviolent, non-sexual offenses,” writes Dan Berger in an opinion article in TruthOut. “To Harris and many centrists in the bipartisan criminal punishment reform world, people charged with ‘non, non, nons’ are the only group that should be subject to non-punitive reforms. So Harris calls for the expungement and sealing of records but only for ‘offenses that are not serious or violent after five years’ of release. She wants to end asset forfeiture—except for ‘transnational gangs and major criminal enterprises’—an exception that will prove the norm for justifying seized assets. She wants to ‘end juvenile incarceration … except for the most serious crimes.’” Harris criticizes the rise in incarceration of women and girls but calls only to “reduce the incarceration of women convicted of nonviolent offenses.” When Harris does address violent crime, her proposal is to study the issue, and her language goes from bold proclamation to tentative slither. When she writes that “one cannot truly reform the system without,” most of us expect her to say what has been said before, that we cannot effectively reduce mass incarceration without reducing sentences for those with violent convictions. But instead she ends the sentence by promising to “study the effects of how best to hold individuals convicted of violent offenses accountable.” She acknowledges that this has already been researched, as “studies show that merely imposing excessively long sentences does not improve results of preventing individuals from re-offending.” Her suggestion is to convene a commission to “study this issue and provide recommendations based on evidence-based findings.” Most of Harris’s proposals would be undeniably positive and welcome changes: taking clemency decisions out of the purview of the Department of Justice, implementing sentence review to ensure that those serving long sentences still need to be incarcerated, and ending mandatory minimum sentences at the federal level, for example. But those changes, if implemented, would not ensure that a single person served a single day less: They all rely on the actions of people who are generally already part of the overly punitive system we have now. And, with the exception of sentence review, which is new, the suggestions are already popular among Democrats. The section of her plan that focuses on prosecutorial accountability curiously has no mention of Harris’s record nor her current embrace of her prosecutor identity. And although it suggests undeniably good things, like data collection and DOJ investigations of prosecutorial offices that commit systemic misconduct, she also would give prosecutors more money (as she would for police). She also avoids the areas where she herself received criticism. The final section, on protecting vulnerable populations, only discusses rape kit backlogs in the criminal justice context, as if survivors of rape are the only vulnerable people, and not the thousands of people who are degraded and dehumanized through the criminal system on any given day. Much of that brief section is devoted to touting her achievements going after big banks and for-profit colleges. Harris defends her record by saying that she was in office during a tough-on-crime time, but she was in law enforcement until early 2017, long after the beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement. And she won her first race, for San Francisco district attorney, by ousting an actual progressive from office. “Terence Hallinan was one of the only prosecutors in America bucking the trend” of severity, writes Lee Fang for The Intercept. “A legendary civil rights activist, defense attorney, former city supervisor, and an outspoken advocate for marijuana legalization,” Hallinan hired “more minorities and reformists,” instructed his deputies to stop using peremptory strikes against non-white potential jurors, believed that sex work was not a criminal offense, promoted alternatives to incarceration, and treated police abuse as seriously as any civilian assault. His tenure was cut short by Harris, who explicitly lobbied for law enforcement support, and ultimately defeated Hallinan by fearmongering, painting Hallinan as weak and ineffective. “Let’s be clear,” she said in one debate. “I’m not running for public defender.” Also during the campaign she announced, “It is not progressive to be soft on crime.” All of this means that even if Harris’s criminal justice plan were the most comprehensive, visionary, and progressive—which it is not—Harris would still have to square it with her troublesome record, which she has not. And if she weren’t going to opt for any of those, Harris might want to consider focusing less on herself, and more on the task of ending mass incarceration. |