Harris County D.A. Ran as a Reformer. So Why is She Pushing High Bail for Minor Offenses?

An email obtained by The Appeal shows Kim Ogg’s office is intentionally asking for unaffordable bail amounts to hold certain people in jail in Texas.

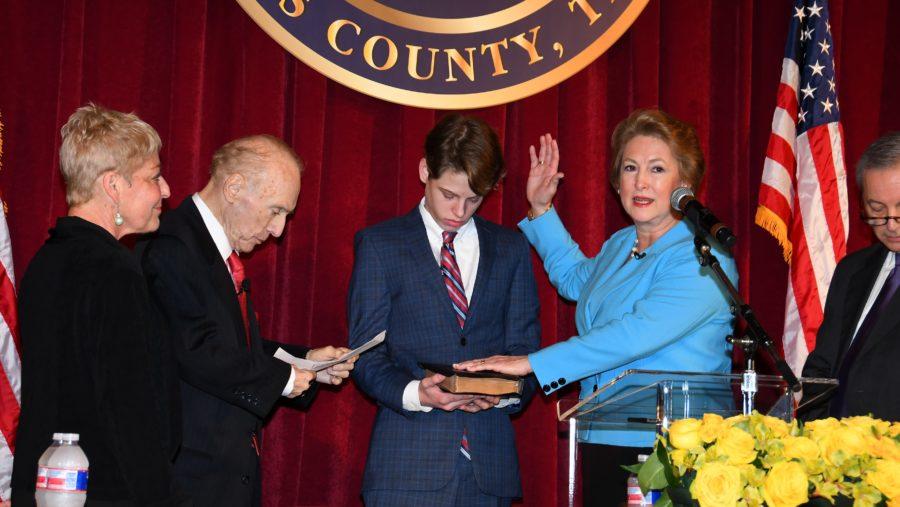

When Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg was running for her seat in 2016, she took a firm stance against the Texas county’s cash bail system, calling it “a tool to oppress the poor” on her campaign website. But internal instructions obtained by The Appeal indicate that her office is still pushing for high bond amounts for minor crimes like marijuana possession and criminal trespass.

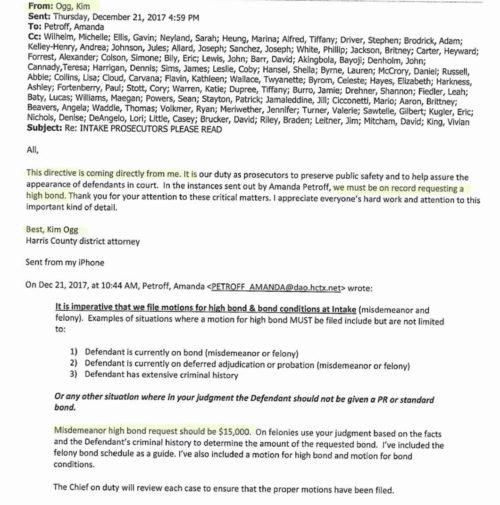

The email from Ogg expressly asks prosecutors in her office to request high bond amounts for select defendants, emphasizing that “misdemeanor high bond requests should be $15,000.”

Sent privately to attorneys in her office in December, Ogg wrote: “This directive is coming directly from me.”

While running for election, Ogg generated excitement among criminal justice reform advocates with her outspoken pronouncements against the bail system. On her campaign website, she blamed the incumbent DA and judges who “utilize a bond schedule that is now the subject of a multi-million dollar lawsuit because it is unconstitutional.”

“Holding low-level offenders who can’t bond out because they’re too poor is against the basic principles of fairness,” she told The Guardian in April 2017, three months after she assumed office.

But the email Ogg sent in December reminded her staff it was their “duty as prosecutors to preserve public safety and to help assure the appearance of defendants in court. In the instances sent out by [assistant district attorney] Amanda Petroff, we must be on record requesting a high bond,” she wrote.

The Petroff email she forwarded said it was “imperative that we file motions for high bond & bond conditions at intake (misdemeanor and felony).”

The examples she gave were defendants currently on bond, currently on deferred adjudication or probation, those with extensive criminal history, “or any other situation where in your judgment the defendant should not be given a PR [personal recognizance] or standard bond.” Petroff wrote that misdemeanor high bond requests should be $15,000.

Trisha Trigilio, a lawyer for the ACLU of Texas, called the email “frustrating.”

The Appeal found a number of misdemeanor cases in which Ogg’s office filed motions for high bond, but where the judge disagreed, ultimately setting bond lower.

In February, Ogg’s office asked for $15,000 bond for John Crain, a man charged with misdemeanor theft, because it said he was under the supervision of a criminal justice agency at the time. In that case the judge set Crain’s bond at $1,000. Also in February, Clifford Holmes was charged with Class B possession of less than two ounces of marijuana. The DA’s office filed a motion asking for $15,000 bond because it said Holmes was already out on deferred adjudication for unlawfully carrying a weapon in his car. The judge disagreed with the amount, setting bond at $1,000. Eric Allen, accused of trespassing, had his bond set at $3,000; the DA’s office had requested $20,000. Also charged with trespass, Jermaine Chambers’s bond was set at $2,500; Ogg’s office had asked for $15,000.

In one case in May, Ogg’s office asked for bond “of no less than $100,000.” The accused, James Sam, had been charged with a misdemeanor violation of a protective order (he messaged someone he was forbidden from contacting). In that case the judge granted a bond of $10,000, 10 percent of what the DA’s office had requested.

Asked to look at these specific cases where the DA’s requests for high bonds had been refused, Trigilio, a staff attorney for the ACLU of Texas told The Appeal, “No matter what someone’s criminal history [is], these are such minor offenses…the request for bail exceeds what some of these people make in a year.”

The crimes these people were accused of—offenses like criminal trespass, a charge often levied against homeless people sleeping on the street—were nonviolent, Trigilio pointed out. “[Criminal trespass] is one of the lowest level crimes you can be charged with, and the bond amount far exceeds what someone could ever be fined for this offense. It’s frustrating when you see what’s in that email [from Ogg] if you compare this to what she says publicly.”

“Prosecutors have a responsibility to work for what’s fair, not what’s harsh,” Trigilio continued. “Bail recommendations should always be individualized, and they should be the least restrictive conditions possible.”

She said it’s never appropriate for a DA to ask for $15,000 bond for charges like marijuana possession, and pointed to research showing that releasing people based on their promise to pay if they don’t turn up in court is just as effective as requiring money bail up front. “Forcing someone to buy their release doesn’t increase rates of appearance in court,” she said. “It actually makes things worse—people wind up sitting in jail for longer, which disrupts their lives and increases the chance that they’ll commit more crimes in the long run.”

In 2016, the nonprofit groups Civil Rights Corps and the Texas Fair Defense Project sued Harris County on behalf of poor defendants arrested on misdemeanors who couldn’t afford to pay bail. In April 2017, a federal district judge issued an injunction calling the county’s bail practices unconstitutional. That order was largely upheld in February by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which found that Harris County’s bail practices discriminated against poor misdemeanor defendants. Ogg filed a brief in support of bail reform in 2017 and celebrated the district judge’s ruling, saying, “From now on, people can’t be held in jail awaiting trial on low-level offenses, just because they are too poor to make bail. … We welcome the ruling and will comply fully with it.”

The federal district judge issued new rules in June requiring Harris County to release people charged with certain offenses like drunken driving or writing bad checks if a person with money in the same situation could make bond. On Tuesday, Harris County misdemeanor judges claimed in federal appeals court that the new rules would endanger public safety.

When asked to account for his office’s high bond requests for misdemeanors, Harris County’s First Assistant District Attorney Tom Berg blamed a risk-assessment tool which, he told The Appeal, is being misapplied by judges to set bond too low. “If we remained silent the magistrate would likely set bail and conditions based on the tool,” he wrote in an email. “The police and the public would also accuse us of ‘setting’ a low bail even though it was the magistrate who did it.”

Berg argued there is a small subset of people charged with misdemeanors who present a flight risk or are so dangerous that they can’t be trusted to reappear in court or keep out of trouble, but Texas allows preventive detention only under strict conditions. As a result, prosecutors are strategically requesting bond amounts they know the individual can’t afford, Berg said. “We are still operating under a cash bail system where if we want to hold someone because that person is dangerous, the only mechanism we have is to ask for cash conditions greater than a person can make.”

Berg said the issue is more nuanced than many people understand. “We really are trying to get most of the people out of the jails. … We’d like to divert those minor cases completely out of the criminal justice system. In many respects we’re trying to make the best of what we’ve got here until it can be reformed.”

Berg said the DA’s request for a high bond is made in writing for “public safety reasons,” even in nonviolent misdemeanor cases—“in order to memorialize our justification and articulate why a particular defendant is a greater risk of flight or danger than that predicted by the risk assessment tool.”

Jocelyn Simonson, Associate Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School, said Berg’s statement is an admission that the DA’s office is using money bail as a form of de-facto pretrial detention. “[They’re admitting] to asking for high bail with the clear intention of causing someone to be held in jail pretrial because that person can’t afford to pay the amount they’ve requested.

“[Berg] makes it sound like they have no choice but to ask for high bail. That’s not true. There’s an alternative. Ogg could stand up on the record in every case and say this office is not going to ask for money bail for an amount someone can’t afford because it offends notions of fairness. But she’s not saying that.”

Jennifer Laurin, Wright C. Morrow Professor of Law at The University of Texas School of Law, noted that prosecutors and defense attorneys are often still operating with limited information about a case when bond is being set. “It’s at an early stage in a prosecutor’s relationship with the case and the defendant,” she said, “so I think it’s fair to be skeptical of unilateral determination by prosecutors that someone is more dangerous than indicators suggest.

“What kinds of potential biases are entering into that calculus? It should give one pause about a practice continuing where prosecutors can unilaterally reach those conclusions without an adequate airing of the basis for them.”

What’s more, a study published in 2016 by the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice, a national criminal justice project at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, said the cash bail system could actually harm public safety. In Harris County alone, the study found that defendants accused of misdemeanors who were jailed before trial were 25 percent more likely to plead guilty, 43 percent more likely to be sentenced to jail, and ended up receiving sentences more than double the length of defendants in similar situations but who were not incarcerated before their trials.

In addition, it found that in Harris County, pretrial detention had what it called a “criminogenic impact,” appearing to actually cause those who were detained to commit more crimes after their release.

Paul Heaton, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania and one of the study’s authors, told The Appeal that a prosecutor may think high bail is the only tool available to detain individuals that they believe present a substantial risk to public safety. “High bail can amount to code for ‘we think this type of defendant is enough of a risk we shouldn’t be releasing them,’” he said.

But Heaton also offered the following scenario: If someone is arrested for disorderly conducted and can’t afford bail, they might spend a couple of days in jail. “What’s their employer doing during that time? What if a rent payment is due? What’s happening to their kids? There’s potentially a lot of disruption.”

If an arrest is for a minor misdemeanor, Heaton said a defense attorney may recommend that her client pleads guilty so he will be released for time served. “If that person says ‘but they got the wrong guy’ the attorney could argue the case, but the trial date may not be for another week. Research shows detaining people destabilizes their lives in terms of housing, employment, family relationships, and transportation. It’s ironic that these policies which are enacted to preserve public safety actually end up creating more crime down the road.”

Sandra Thompson, director of the Criminal Justice Institute at the University of Houston, agrees that a large part of the problem is with the traditional money bond system that Texas employs. “What judges are allowed to do varies depending on the charged offense, not based on results of a validated risk assessment,” she told The Appeal. Thompson said it’s hard for an outsider to evaluate the cases that The Appeal found without studying them closely. “If prosecutors are asking for money bail and it’s high, and yet the risk assessment says this person is not a high risk, then that’s a problem.”

Laurin said that if Ogg’s position is that she’s operating within a system not of her making; that her hands are tied and that she has to ask for high bond because she’s determined that some people will not turn up at court or will reoffend if they’re freed, then “a better approach would be to engage with the county and magistrates to get a functional risk assessment tool … let’s get an objective process in place we can all agree on.”

But the policy could be a political “hedge,” Laurin said, that Ogg wants simultaneously to be seen as progressive but that she’s also throwing a bone to anyone not on board with the reforms that the bail litigation has pushed for or who are risk-averse to the political fallout from the public safety consequences of releasing someone who could then reoffend.

“It’s possible both of these things are in the mix,” she said.

The ACLU’s Trigilio said it’s important to remember that the Supreme Court has held for decades that when bail is designed to ensure appearance, it cannot be excessive. “Courts are required to consider less-restrictive alternatives to make sure a person comes back to court. If a promise to pay for failure to appear is going to do just as good a job as making people pre-pay for release—which is what study after study shows—then courts should be releasing people based on their promise to pay. What’s most frustrating is if anyone should know this research, it’s officials in Harris County.”