‘Habitual Offender’ Laws Imprison Thousands for Small Crimes—Sometimes for Life

Data obtained by The Appeal show nearly 2,000 people in Mississippi and Louisiana are serving long—and sometimes life—sentences after they were labeled “habitual offenders.” But most are behind bars for small crimes like drug possession.

This piece was produced thanks to a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

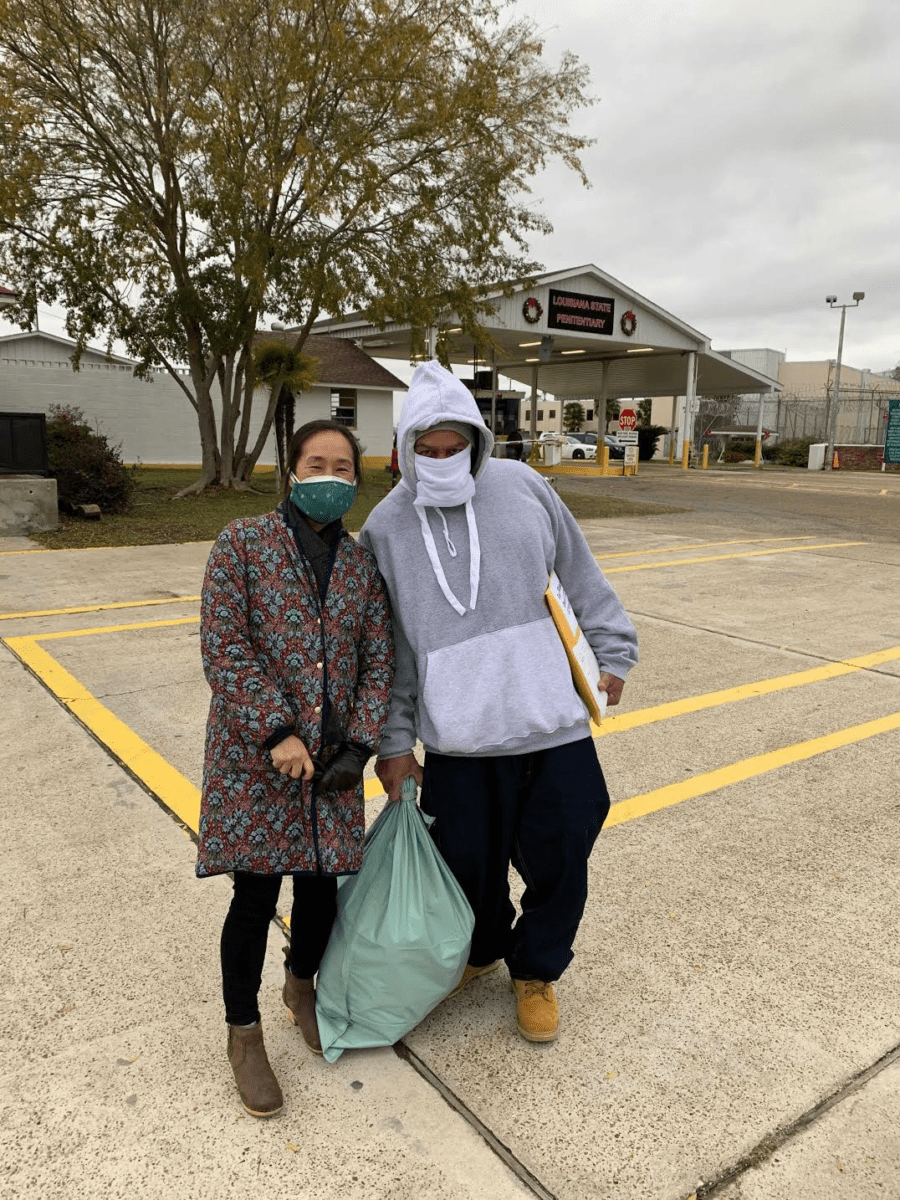

For most of her life, Faith Canada had only known her father, Fate Winslow, behind bars. She didn’t have much hope she’d see him as a free man—thanks to Louisiana’s so-called habitual offender laws, he was serving life without the possibility of parole for a marijuana conviction. But a few days before Christmas in 2020, Winslow, then age 53, walked out of the Louisiana State Penitentiary. The Innocence Project New Orleans had taken on his case and took advantage of a change in Louisiana law that allowed for claims based on ineffective counsel to apply to sentencing, rather than just verdicts.

Winslow took his daughter to lunch. “He really wanted to try the McDonald’s fish sandwich,” Canada told The Appeal. It’s one of her favorite memories. They listened to Boosie Badazz in the car. The rapper had served five years on drug charges alongside Winslow in Louisiana State Penitentiary, widely known as Angola.

Father and daughter talked about life. A few years earlier, she’d lost her son during childbirth, and doctors told her she couldn’t get pregnant again. Winslow told her he believed a miracle would happen. “He really wanted a grandchild,” she told The Appeal. “We mainly just caught up on everything and he told me how much he missed me.”

At lunch, they took photos. Winslow grinned ear to ear, showing off a piece of his sandwich. Another picture shows the two hugging, with the same wide smile Canada inherited from her father. Before the outing, virtually the only pictures of him were in an orange uniform, frowning in mug shots that marked his four arrests over the course of decades. Winslow’s last arrest, in 2008, sealed his fate as a habitual offender sentenced to die in prison.

That year, he’d been living on the streets when an undercover officer tried to buy $20 worth of pot from him. Winslow, who said he accepted the offer because he was hungry, got cannabis from a dealer and gave it to the police. Winslow’s cut was $5. The dealer was not arrested even though the marked $20 bill was found on him.

Winslow, who is Black, went to trial. Two Black jurors voted not guilty. Ten white jurors voted guilty. Even though his previous crimes were nonviolent and separated by decades, Winslow was convicted and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. “It was a very small amount of marijuana. It was ridiculously small,” a juror recalled years later. But it didn’t matter. Following the passage of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the much-criticized law proposed by then-Senator Joe Biden that significantly increased funding for police departments and prisons, Louisiana and many other states began to punish repeat offenders more harshly regardless of the severity of their crimes.

In the nearly 30 years since the passage of the crime bill, habitual offender statutes fueled some of the worst excesses of the prison system. The laws created a much larger geriatric incarcerated population whose healthcare costs billions nationally, ripped families and communities apart, overburdened understaffed facilities, and normalized the idea that swathes of the U.S. population are irredeemable.

Yet, according to an investigation by The Appeal, these nearly 30-year-old policies are still punishing people like Winslow based on their “habitual” status, rather than on how much of a threat they may pose. The Appeal took a deeper look at Louisiana and Mississippi, states that changed their laws in 1994 or 1995 and now have some of the highest rates of incarcerated people in the country. The Appeal sent freedom of information requests to both the Mississippi Department of Corrections and Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections for data on people serving 20-year-plus sentences and, where possible, information regarding whether their sentences had been enhanced by a habitual offender statute. We broke the data down by race, crime, time served, and sentence. In total, datasets suggest there are close to 2,000 people currently serving long sentences enhanced by habitual offender statutes in these two states.

A small number of these people in these two states committed serious crimes. But most are serving 20-plus years primarily because of habitual offender status, where the triggering offense was drug possession, drug sale, illegal gun possession, or another crime besides murder or rape. Scores of people are serving virtual or literal life sentences for nonviolent drug possession.

“There’s got to be something said for someone who breaks the law over and over,” Kevin Ring, president of the nonprofit Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM), told The Appeal. “But as with most things in the U.S. system, we just take a sledgehammer to the problem and lose all sense of proportionality.”

Despite walking back his “tough on crime” history during the 2020 presidential campaign, President Joe Biden has yet to do anything concrete, such as a mass clemency offer, to begin to rectify the consequences of the old policies. In fact, he recently pledged to funnel more money to state and local police, even as misguided pro-incarceration policies from 30 years ago are still destroying lives like Canada’s and Winslow’s.

“It was a fourth offense from [nonviolent] stuff he did when he was younger,” Canada, now age 23, said. “For that you took him away.”

During the 2016 and 2020 elections, many high-profile Democrats tried to deflect from the impacts of the 1990s “tough on crime” spree that culminated in the 1994 crime bill. In 2016, former President Bill Clinton blamed Joe Biden.

“Vice President Biden [. . .] was the chairman of the committee that had jurisdiction over this crime bill,” Clinton said to a group of Black Lives Matter protesters. But in 2019, Biden blamed Bill Clinton.

“I made sure there was a setup in that law that said there were no more mandatories, except two that I had to accept,” Biden said at a New Hampshire presidential campaign stop. “One was the President Clinton one of ‘three strikes and you’re out,’” Biden said.

Although federal prisoners make up roughly 12 percent of the U.S. prison population, the federal government led the way on mass incarceration by way of example.

“The federal prison population is still the largest prison population, compared to any state,” Inimai M. Chettiar, federal director of the nonprofit Justice Action Network advocacy group, told The Appeal. “And, there’s also public and national attention paid to federal policy, in a way that isn’t paid to smaller states.”

There were concrete features of the federal bill that gave states funds to hire more officers and build more prisons. “The federal crime bill not only increased the federal prisoner population but gave financial incentives to states to increase prison populations,” she said. In 34 states, the average length of stay for people convicted of crimes released from prison jumped 36 percent between 1990 and 2009, according to a 2012 Pew Charitable Trusts study.

“This idea that the crime bill generated mass incarceration—it did not generate mass incarceration.”

Joe Biden Nashua, New Hampshire, May 14, 2019

Habitual offender laws precede the 1990s “tough-on-crime” bonanza, but they became widespread throughout the country after the passage of the ‘94 crime bill. After Clinton popularized “three strikes and you’re out” during the 1994 State of the Union address—arguing that anyone convicted of a serious, violent crime after two prior convictions should be sent to prison for life—many states either introduced habitual offender laws or made existing ones harsher.

In Louisiana, a second offense allowed prosecutors to seek more prison time. (The state’s habitual offender law was first enacted in 1928 but was made more punitive in the 1990s.) That’s how one person named Fair Wayne Bryant was sentenced to life in prison after being accused of trying to steal a pair of hedge clippers. He had prior convictions for attempted robbery, possessing stolen goods from a RadioShack, trying to forge a $150 check, and breaking into a home and stealing.

There are few people who habitually commit murder or violent rape. There’s a 5.3 percent recidivism rate among sexual offenders three years after they’re released, according to the Justice Department. A 2019 study found that despite a handful of high-profile cases, people convicted of murder are unlikely to commit another homicide, since “most murders are opportunistic and singular.” Those offenses also carry years to decades in prison, so that’s not where habitual offender laws have the greatest impact. Instead, the statutes entrap people who’ve been in trouble with the law multiple times regardless of how serious their crimes are.

Fate Winslow was sentenced to life without parole for a pot conviction two years after President Barack Obama admitted in 2006 to inhaling when he smoked weed. “That was the point,” Obama sassily said when asked.

In 2017, the Hattiesburg Police Department in Mississippi surrounded the apartment of then-34-year-old Allen Russell. When he didn’t respond to their calls to open the door, officers broke into the house and found Russell pulling himself into the attic. They flung a chemical agent into the attic to smoke him out. Police said Russell was a person of interest in a murder. While at his home, the officers found five baggies of cannabis, and in 2019, Russell was convicted of possessing more than 30 grams of the drug. Prosecutors brought in his prior convictions: two home burglaries in 2004, for which he spent eight years in prison, and a 2015 gun possession charge, for which he served two years. Because of the state’s habitual offender laws, the pot charge generated a sentence of life without parole. Russell is still in prison.

In the mid-1990s, Mississippi instituted some of the most restrictive habitual offender laws in the country and virtually did away with parole for repeat offenders. “Essentially, the federal government gave financial incentives for states to implement stricter sentencing requirements around ‘three strikes, you’re out,’ and to limit parole eligibility,” Russ Latino, president of the nonprofit political advocacy group Empower Mississippi, told the Mississippi Free Press in 2021.

According to data analyzed by The Appeal, as of August 4, 2021, there were nearly 600 people in Mississippi who were serving 20 years or more with no parole date and were considered habitual offenders.

The state also has the third highest incarceration rate in the country. The state prison population more than doubled between 1994 and 2008, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. after the state did away with parole for people convicted of multiple crimes. Jake Howard, the MacArthur Justice Center’s legal director in Jackson, Mississippi, said the law is still used as a cudgel for prosecutors to strike plea deals, greatly discouraging trials. “It’s a stick to make people plea,” he told The Appeal. “If you plead guilty, they might drop that habitual charge.”

Pressuring suspects into giving up their right to trial is especially striking given the racial breakdown. In Mississippi, 75 percent of “habitual offenders” are Black, while 25 percent are white. (Other racial groups make up a negligible number.) That’s a higher racial disparity than the already high race disparity of the prison population overall: In 2018, 58 percent of Mississippi’s prison population was Black. Black people are only 39 percent of the state’s population.

One of the five people affected by these laws and convicted of first-degree murder, Jacolby Newell, was convicted of committing a 2013 burglary with two other men, during which one of the group shot and killed someone else. Newell will serve a total of 46 years and is not eligible for parole because an earlier burglary charge was counted separately—in this case, Newell’s “two strikes” were enough to result in almost half a century in prison. Another of the five, Devin Thornton, was labeled a habitual offender based on a previous felon in possession conviction and was given 40 years.

Another handful of habitual offender cases involve attempted murder. In 2013, James Smith was charged with sexually assaulting two young boys and will serve 72 years in prison without the possibility of parole after he allegedly cut one of the boys’ throats. (The boy survived.) In February 2016, 38-year-old Virgil Jarvis and his girlfriend got into a fight—and as she fled the scene in a car, Jarvis ran alongside the vehicle and fired his gun, hitting her in the arm. She was treated for her injuries and left the hospital that night. Jarvis was sentenced to 27 years. In addition to the shooting, he was charged with being a felon in possession of a firearm and with methamphetamine possession and is not eligible for parole.

Ten more Mississippi men were charged with second-degree murder and sentenced with habitual offender enhancements. Troy Roberts was sentenced to 30 years after he shot his wife during a fight—he was labeled a habitual offender because he was charged with possession of a firearm by a felon. Another man, Stephen Hagin, says he was hallucinating from drug use when he killed another man over a $100 meth deal. Hagin is now serving 40 years as well as an additional eight for having previously stolen a car.

As many criminal justice researchers have long pointed out, violence is usually a young man’s game. Based on 2015 data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Marshall Project reports that homicide rates peak at 19, while forcible rape is most common among 18-year-olds. A 60-year-old who’s been in prison for decades is not likely to throw on a mask and gun down a bank teller. According to a 2017 report from the United States Sentencing Commission in which more than 25,000 people released from prison were monitored over an eight-year period, only 13.4 percent of people over age 65 were rearrested, compared to 67.6 percent of people studied who were younger than 21.

Of the nearly six hundred habitual offenders in Mississippi, 20 total men were convicted of rape and given long sentences without parole because of their habitual offender status. Of that number, seven were convicted of statutory rape. One man was convicted of both charges. One is serving a 100-year sentence for attacks he allegedly committed in 2000. But with or without habitual offender laws, people who are convicted of murder or rape are already likely to serve significant time in prison: In Mississippi, first-degree murder, for example, can carry a life sentence with or without parole.

The majority of habitual offender convictions analyzed by The Appealare linked to possession of drugs, possession of firearms, or contraband in prison.

In the most extreme cases, multiple people convicted of drug crimes were given virtual life sentences because of their habitual offender status. Perry Armstead is serving 63 years for five charges of cocaine possession and sales. Keith Baskin is serving 60 years for possession of cannabis with intent to distribute. Timothy Bell is serving 80 years after being convicted of possessing a firearm as a felon and selling meth twice. Malcolm Crump is serving 56 years for selling meth on three occasions. Paul Houser got 60 years for meth. Anthony Jefferson got 60 years for possession of cannabis with intent to distribute.

In other words, these people charged with drug or gun possession are all serving longer sentences than some people charged with far more serious crimes. Worse yet, that list does not include the people in Mississippi sentenced to life without parole for nonviolent drug crimes due to their habitual offender status.

In 2014, Kevin Allen sold $20 worth of pot to his best friend, not knowing that police had squeezed the friend—whom Allen had known since the late ’90s—to work as an informant. The friend testified against Allen at trial. “He set me up,” Allen told The Appeal. Allen says the pair haven’t talked since facing off in court.

Eleven jurors voted guilty, while one voted not guilty. Allen expected to be sentenced to 20 years, but prosecutors activated Louisiana’s habitual offender law to sentence him to life without the possibility of parole. “When they gave me life, I couldn’t believe it,” Allen said. “Why? I didn’t kill nobody. Didn’t rob nobody.”

Before 1994, Louisiana mandated life without parole for a third conviction of violent or drug felonies—however, after 1994, life without parole was mandated if any one of four felonies was on the list of violent or drug offenses.

There are nearly 900 people serving sentences longer than 20 years in Louisiana because of habitual offender statutes who aren’t eligible for parole. (Overall, there are more than four thousand people serving life without parole in the state.) Like Allen, more than two-thirds of offenders serving life in Louisiana are Black.

We both [know], no money, no justice. That’s just the way the world is.

Fate Winslow as told to The Intercept in 2018

According to data acquired through a freedom of information request, the most serious crimes are in the minority. Less than 3 percent of those imprisoned due to habitual offender status were convicted of first-degree murder. Slightly less than 5 percent are serving time for second-degree murder. Almost 6 percent are serving time for rape. Meanwhile, 12.6 percent are serving 20-plus years because of habitual offender statutes triggered by a drug crime. Of those serving decades for drug crimes, 49 people were convicted for possession, 34 for possession with intent to distribute, and 31 for distribution.

One of those men convicted of drug possession is Eugene Jarrow. Jarrow pleaded guilty to armed robbery in the 1970s. In 1988, he was convicted of cocaine possession with intent to distribute. More than 10 years later, in 1999, he was found guilty of marijuana possession and attempted cocaine possession and, because he was considered a habitual offender, sentenced to life without parole. He’s 61 years old.

In October 2000, Rene Decay was allegedly caught with over 400 grams of cocaine, and also charged with attempted possession of 400 grams. In addition, he was charged with possession of a firearm by a convicted felon. He was sentenced to 40 years for cocaine possession, 20 years for attempted possession, and 15 years for the firearm, to be served consecutively. A trial judge overturned the first sentence and resentenced him under the habitual offender statute to life without the possibility of parole just for that single incident.

In 2005, Blaine Blanks broke into a home. When the homeowner returned home, Blanks ran off with a single earring and some meat he had found in the freezer. Later that year, when detectives searched his mother’s home, they found a plate that turned out to have cocaine residue on it. Blanks was sentenced to 24 years.

Many of these cases make little logical sense. Fate Winslow’s sentence made so little sense to his daughter Faith Canada that she took criminal justice courses in college. One day, she walked into class, and to her great shock, they started discussing her father’s case. “At the end of class, I stood up and asked if I could say something,” she recalled. When she told them Winslow was her father, the other students and the professor were speechless. “It’s so, so wrong,” she remembers the professor saying afterward.

In 2019, lawyers with the Innocence Project New Orleans took up Winslow’s case. Earlier that year, a court ruling set precedent for an appeal challenging Winslow’s sentence, rather than his conviction.

One day, Canada got a call from her dad. “Baby, I’m getting out !” Canada recalled him saying. “l’ll see you! I’m ready to start my life over, get everything together.”

Canada said he “was so excited. So excited! When my dad got out, he was in his happiest moments. You never saw him frowning. Always such a good heart.” The Last Prisoner Project, a nonprofit that lobbies for people in prison for drug crimes, helped him financially. He insisted on buying his daughter a car. “It was sweet,” Canada said. “Make sure it’s a good car!”“Make sure you check the oil!” he fretted to the mechanic.

On a Wednesday in May 2021, five months after Winslow got out, Canada got a phone call from her aunt. Her father’s body had been found in a car. He’d been shot dead. Canada says she started screaming.

Since then, it doesn’t appear that police have found any serious leads in the case. “They don’t care,” Canada bluntly concluded about law enforcement. Every time she’s called police for information, she says, she’s given the runaround.

The Shreveport police department in Louisiana has previously faced criticism over its low clearance rate of homicides. In 2016, there were 46 murders and officers made 11 arrests. The same police department that took all of one night to arrest and send Winslow to prison for life for $20 of pot has yet to find his killer, close to two years later. The Appeal sent a request for comment to the Shreveport PD and did not receive a response.

A few months after her father’s death, Canada became pregnant, just as her dad had prayed she would. She had a healthy baby boy in March 2022. “I can’t wait to tell him all about his grandfather and how much he wanted him,” Canada said. She still cries all the time. “You took him away, he came back, you took him away again, and he’ll never come back now. I’ll never be daddy’s little princess.”