America’s Most Notorious Jail Keeps Getting Worse

A horrific death and the high-profile booking of former President Donald Trump propelled Georgia’s Fulton County Jail into the national spotlight. But heightened scrutiny has done nothing to improve conditions.

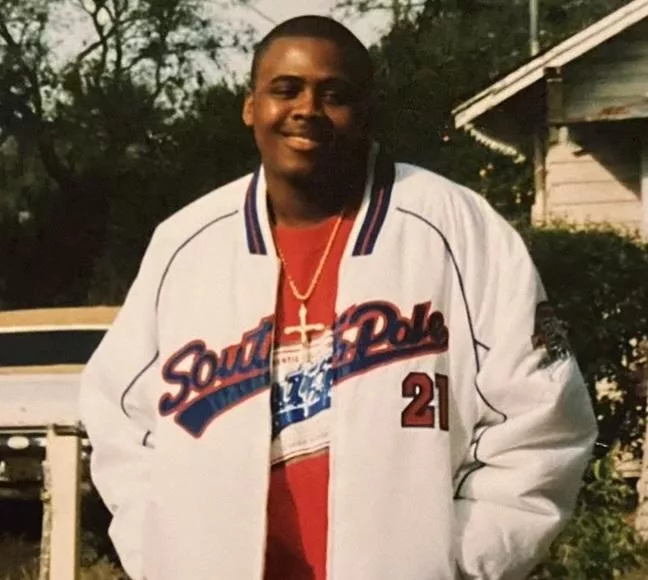

One year ago Wednesday, 35-year-old Lashawn Thompson was found inside a squalid cell at Georgia’s Fulton County Jail, covered in lice and feces.

At the time of his death, most people held in Thompson’s unit, which housed individuals with mental illness, were kept in similarly horrific conditions. But the public was largely unaware of his death or the circumstances around it until more than six months later when his family released haunting photos of Thompson’s cell and body.

The harrowing details of Thompson’s demise sparked a flurry of local, national, and international news stories, making it one of the past year’s most widely covered and condemned jail deaths. In July, the Justice Department announced that it had launched a civil rights investigation into conditions at the Fulton County Jail.

Since then, the jail’s notoriety has only grown. In August, former President Donald Trump appeared at the Fulton County Jail to be booked on charges that he conspired to interfere with Georgia’s 2020 presidential election results. Once again, the jail’s heinous conditions—from which Trump was spared—were in the news.

But even in the face of increased scrutiny, the situation at the Fulton County Jail only appears to have gotten worse in the year since Thompson died. Last September, Thompson was the seventh person to die under the supervision of the Fulton County Sheriff’s Office in 2022; 10 people have died at the same point this year.

The facility is on pace to surpass last year’s death toll of 15—a number that was five times the 2021 total, according to the sheriff’s office.

Fulton County Sheriff Patrick Labat has said the deaths indicate an urgent need for more funding, more beds in other county lock-ups, and, ultimately, the construction of a new jail that could cost $2 billion. In a statement to The Appeal, Labat said a new detention facility would “relieve the dangerous overcrowding, improve security, provide humane detainment and most importantly save lives.”

Local advocates have pushed back against Labat’s claims, noting that the county has sunk millions of dollars into the jail and sent hundreds of people to other lock-ups. The county is now considering sending detainees out-of-state to a Mississippi jail.

To reduce jail deaths, more people must be released, not just moved from one lock-up to another, said Devin Franklin, policy counsel at the Southern Center for Human Rights, an Atlanta-based civil rights group.

“Everything that [Labat] suggests has been wrong,” said Franklin. “They got extra beds, and what we’ve seen is that people are dying at a faster rate than they were dying before. We literally see that more beds do not save lives.”

Since January, nine people have died while detained at the Fulton County Jail. Another died in a section of the Atlanta City Detention Center run by the Fulton County Sheriff’s Office.

A 26-year-old man living with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder was the first person this year to die at the Fulton County Jail, according to jail records. An officer found him after detainees had banged on the door to get the staff’s attention.

The man was taken to the hospital and pronounced dead less than 15 minutes after arriving. The medical examiner determined he had died from a seizure disorder, according to a postmortem report.

In March, a 24-year-old man who had bipolar disorder was found unresponsive in a common area of the jail. Surveillance video showed a detainee cleaning up vomit near the man’s head before staff found him, according to the medical examiner’s report. The medical examiner concluded he’d died of a seizure.

The following month, a 65-year-old man was found unresponsive in his cell, taken to the hospital, and pronounced dead, according to jail records.

(The sheriff’s office has not published press releases on these deaths, so The Appeal is not releasing their names out of respect for their families’ privacy.)

Nineteen-year-old Noni Battiste-Kosoko died in Fulton County Sheriff’s Office custody on July 11. She was found unresponsive in her cell at the Atlanta City Detention Center. Although the facility is separate from the Fulton County Jail, the teen had been detained in an area run by the sheriff’s office following an agreement last year to transfer up to 700 people from the overcrowded jail to the Atlanta lock-up.

Battiste-Kosoko had struggled with mental illness and homelessness, according to news reports.

Later that month, 40-year-old Montay Stinson was found unresponsive in his cell at the Fulton County Jail, according to the sheriff’s office. He had been at the jail since October 2022, held on a $3,000 bond.

In August, four more people died at the Fulton County Jail in the weeks after county commissioners approved a $4 million settlement with Thompson’s family. These included 66-year-old Alexander Hawkins, who was detained on a $5,000 bond for shoplifting, according to the sheriff’s office, and a 34-year-old man. Both were found unresponsive in cells in the medical unit.

One person has died so far in September, 24-year-old Shawndre Delmore. He was held on a $2,500 bond and had been at the jail since April, according to the sheriff’s office.

Almost everyone held at the Fulton County Jail is detained pretrial and legally presumed innocent. As of September 12, all but approximately 40 of the more than 3,500 people locked up in the jail were awaiting trial, according to the sheriff’s office.

In the year since Lashawn Thompson’s death, the Fulton County Board of Commissioners has approved millions of dollars in funding for the jail, but the death toll has continued to rise.

Shortly after photos of Thompson’s body became public, the Board approved, among other expenditures, more than $2 million for wristbands that purport to provide real-time tracking of detainees’ heart rates and blood pressure.

In June, County Commissioners extended the county’s contract with NaphCare, the jail’s for-profit medical provider, despite allegations that the company has provided inadequate and dangerous care to its incarcerated patients. According to an independent autopsy released by Thompson’s family, Thompson had not received his medications for schizophrenia for more than a month before his death. From July 1 through the end of the year, Fulton County will pay the company more than $4.7 million.

“The concerns that have come to light in recent months have not magically gone away or been resolved, but we are making progress,” Labat said in a statement after the vote. “My intent remains to provide the best standard of care for inmates while also ensuring there are no gaps in service.”

In August, County officials requested funds to hire crisis communications firm Burson Cohn & Wolfe “to implement strategic communications” about the Fulton County Jail.

At an August 16 meeting of the County Board of Commissioners, County Manager Richard Anderson sought approval of a $385,000 contract with the firm set to last through the end of the year. Anderson said his office had already begun working with the company in collaboration with the sheriff’s department.

Anderson reminded County Board Chairman Robb Pitts that Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens had previously advised both of them to invest in communications “based on their experience with their Public Safety Training Center,” the contentious project known as Cop City.

A spokesperson for the county told commissioners it had been “challenging” to meet the recent “demand for information.”

The commissioners voted to put the request on hold and ordered all work with the firm to cease.

“This is just throwing money in the trash,” County Commissioner Bob Ellis said during the discussion.

“If you have means, then you get out, and if you don’t have means, you might die,”

Fallon McClure, deputy director at the ACLU of Georgia

With many people locked up in the Fulton County Jail on bond amounts they can’t afford, advocates say prosecutors and judges are also to blame for creating the current crisis. But there are steps they can take to rectify it.

Earlier this month, the Public Defender for the Atlanta Judicial Circuit asked the Chief Judge for Fulton County Superior Court to issue a standing order to allow people held on bond for non-violent charges, as well as those who’ve been detained without formal charges for over a year, to be released on signature bonds. Signature bonds only require a promise to appear in court.

In an email to The Appeal, the public defender’s office said they had not yet met with the chief judge but expected to in the next few days.

A study published by the American Civil Liberties Union and the ACLU of Georgia last year found that almost 300 people were detained at the Fulton County Jail because they could not afford to pay a bail set at or below $20,000—which could mean paying up to $2,500 to be released.

“If you have means, then you get out, and if you don’t have means, you might die,” said Fallon McClure, a deputy director at the ACLU of Georgia.

Last week, the advocacy group Color of Change sent a letter to Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, whose office prosecutes felonies, and Fulton County Solicitor General Keith Gammage, whose office handles misdemeanors and other offenses, calling attention to their role in the crisis.

“At least part of a solution to the problem of jail deaths is just reducing the number of people who end up in the system in the first place,” said Michael Collins, the senior government affairs director for Color of Change.

Ultimately, that is within both Gammage and Willis’s power, said Collins.

Color of Change observed several hearings over the last year and found that prosecutors from Gammage’s office requested money bonds for misdemeanor charges, even though many cases “were rooted in issues of poverty,” according to the group’s letter. As of September 12, 187 people at the jail were held only on misdemeanors, according to the sheriff’s office.

In an interview with The Appeal, Gammage said his office has championed initiatives to keep people out of jail. They are launching a pilot program with the Atlanta-based Policing Alternatives & Diversion Initiative (PAD) to release people who have needs related to mental health, substance use, or extreme poverty to PAD at their first court appearance.

“The most effective way to achieve public safety is to, in fact, connect individuals to services and resources,” Moki Macías, PAD’s executive director, told The Appeal.

As of September 12, over 45 percent of detainees—more than 1,600 people—had not been indicted, according to the sheriff’s office. Advocates have called on Willis to clear the backlog so people are not waiting in legal limbo for months or years in a deadly lock-up. A spokesperson for the DA’s office was not available to provide comment before publication.

“Fani Willis’s office is effectively the gatekeeper,” said Franklin. “There are certainly things that the sheriff could do to treat people better that are in his custody. But at the end of the day, he doesn’t have control over when people go to court or what they’re held for.”