From Gang Allegations to Deportation: How Boston is Putting its Immigrant Youth in Harm’s Way

The Trump administration uses Sanctuary Cities as punching bags in its war against immigrants. But even in the cities taking federal heat for protecting immigrant communities, a little-understood, post-9/11 institution called the “fusion center” is playing a starring — if behind the scenes — role in the Trump-Sessions deportation regime. Despite promises from liberal mayors, local police departments are […]

The Trump administration uses Sanctuary Cities as punching bags in its war against immigrants. But even in the cities taking federal heat for protecting immigrant communities, a little-understood, post-9/11 institution called the “fusion center” is playing a starring — if behind the scenes — role in the Trump-Sessions deportation regime. Despite promises from liberal mayors, local police departments are quietly using fusion centers — and the local gang databases housed in them — to aid ICE in seizing and deporting some of the most marginalized young immigrants in the country.

In Boston, the problem has reached crisis proportions, striking fear into immigrant communities, especially those hailing from Central America.

Local law enforcement is “the tip of the spear” in the Trump deportation machine

On September 21, 2017, Attorney General Sessions came to Boston to speak to federal prosecutors, where — facing protests outside — he delivered a cynical, ominous speech warning his Boston area employees about the threat posed by MS-13, a Salvadoran gang. (Massachusetts is home to over 40,000 people who were born in El Salvador.)

Sessions told the group that he had a message from Donald Trump to MS-13: “We are coming for you. We will hunt you down; we will find you, and we will bring you to justice.” He congratulated Boston-area prosecutors for their 2016 federal indictment of nearly 60 people alleged to be affiliated with MS-13 and asked for more of the same. But the feds can’t do it alone, he said, noting that “street level intelligence and investigation” is key to “successfully investigating and prosecuting this group of thugs.” He called “state and local law enforcement…the tip of the spear” in the fight against MS-13, and described unaccompanied minors as possible “wolves in sheep [sic] clothing.”

While he framed MS-13 as a savagely violent group, Sessions said he’d issued directives to field prosecutors to “renew their focus” not on violent crimes but on immigration offenses, especially where the immigrants “have a gang nexus.”

Months earlier, in the chaotic first few weeks of the Trump administration, Boston’s Mayor Marty Walsh gave a rousing press conference at City Hall, promising to defend the city’s immigrant community against the likes of Sessions and Trump. “Boston was here for me and my family,” the son of Irish immigrants said. “And for as long as I am mayor, I will never turn my back on those who are seeking a better life. We will continue to foster trusting relationships between law enforcement and the immigrant community. And we will not waste vital police resources on misguided federal actions.” Walsh even offered to let immigrants sleep in his office, so no one in the city need live in fear of Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE).

But Walsh’s own police department was at that moment putting immigrant youth at risk of deportation by sharing information with those very federal immigration officials, who were newly emboldened to seize undocumented young people alleged to be gang involved. Indeed, even the Boston Public Schools Police were, and continue to be, involved in what some advocates are now calling a “school to deportation pipeline.”

In order to understand how that pipeline works, Walsh and other city policymakers should take a closer look at both the Boston Police Department’s local spy center and its gang database — which, whether out of ignorance or cowardice, they have largely ignored to date. Then officials should follow the lead of other big cities, and make necessary changes to protect our youth.

Post-9/11 terror hysteria, the war on drugs, and a new immigration crisis

The Boston Regional Intelligence Center (BRIC) is a post-9/11 “fusion center,” originally formed to facilitate the sharing of counterterrorism intelligence among state, local, and federal law enforcement. The federal Department of Homeland Security, the parent agency of ICE, provided initial funding for the spy center when it opened in 2005, and has since given it hundreds of millionsof dollars in grants to support its operations. The BRIC is one of nearly 100 similar centers nationwide that facilitate the sharing of counterterrorism intelligence across different levels of government, with the goal of breaking down stovepipes and providing law enforcement with an infrastructure for “connecting the dots.”

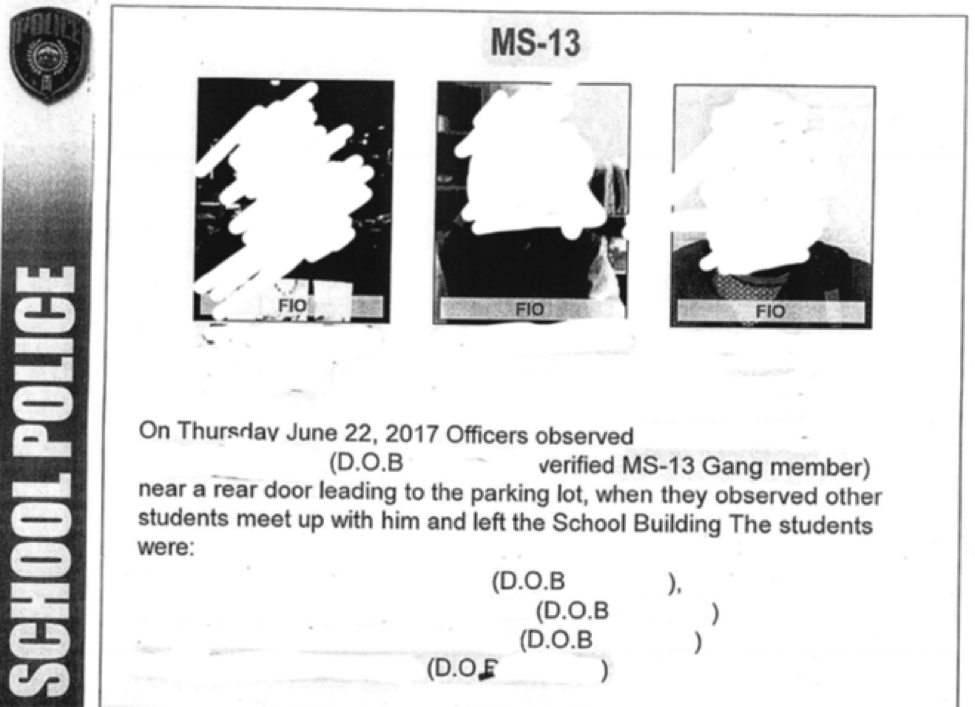

The BRIC is located at BPD headquarters and run by the Boston Police Department. The center collects, analyzes, and shares street level surveillance information in the form of BPD incident reports; reports from Boston School Police; and other types of information, including surveillance feeds from DHS-funded cameras throughout the city, and data from ShotSpotter devices, which listen for gunshots in real time. The center also collects and analyzes field, interrogation, observation (FIO) reports, which are based on police officer surveillance of individuals and groups on the streets, at schools, and in other public places. Often these FIO reports are generated from vehicle stops or stop and frisks, but other times the people monitored have no idea the police are watching them and taking notes about what they’re doing, who they’re with, or what they’re wearing. The Boston Police Department’s gang database also lives at the fusion center, making it easy for ICE agents to access its information.

The BPD’s gang database, like those in other large cities nationwide, operates on a point system. Based on the center’s surveillance, the BPD assigns points; ten points triggers reasonable suspicion of criminal activity, according to BPD policy, enabling officers to classify someone as a gang member and put them in the database. Like other gang database systems, no actual or even alleged criminal activity is required for inclusion in the database. Oftentimes, there is none alleged. For example, if a Boston Police officer assigned to work in a public school says that someone is seen communicating with a person already in the gang database, that’s four points. If law enforcement sees a person wearing a particular color hat or shirt, that’s another four points. If the cop sees a person in a “group related photograph” on Facebook or Instagram, that’s another two points, adding up to ten total. That’s it.

Despite the very low bar for admission into the database, when the Boston Police Department decides someone is a gang member, the designation can have life shattering consequences — especially when the information makes its way into the hands of immigration officials.

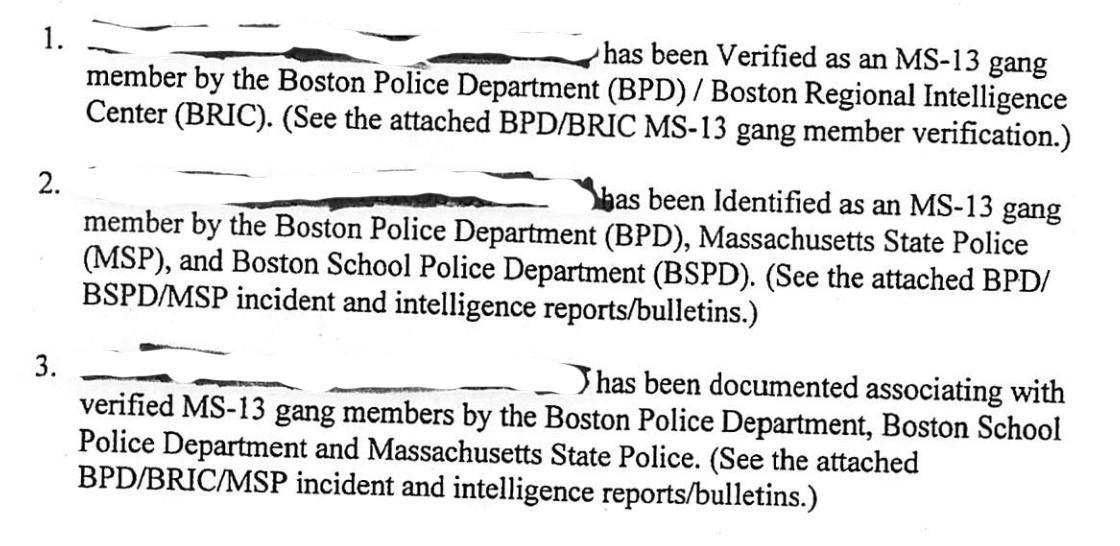

The image below is taken from a Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) case file, which was submitted to a Boston federal court in deportation proceedings against a young Central American Bostonian in 2017. According to his attorney, the young person, whose name we are withholding due to his ongoing immigration court proceedings, has no criminal record; ICE seized him solely because of an allegation of gang involvement in the Boston Police Department’s BRIC gang database.

As you can see, there is no allegation of criminal activity in the “verification report details” that the Department of Homeland Security presented to the immigration judge. It merely includes a number of references to field, interrogation, observation (FIO) reports claiming the young person was seen associating with other young people who are in the gang database. It is purely guilt by association that put this young man in immigration detention. And a large portion of the points come from uncorroborated statements by a school police officer, while the others come from the Boston Police Department and the Massachusetts State Police.

According to local immigration attorneys, Sessions’ commitment to using local law enforcement’s street level surveillance, and the Boston Police Department’s cooperation with those efforts, has led to a spike in arrests of young, mostly Central American people in East Boston solely on the basis of their inclusion in the BPD’s gang database. This bears repeating. Immigration attorneys who work with youth in Eastern Massachusetts confirm that in the past year, they’ve seen an increase in ICE arrests of young Bostonians who have never been arrested or even accused of a crime, solely because they are listed in the BPD’s gang database, and often initially due to statements made by school police officers.

These seemingly targeted arrests of Central American youth raise the question of whether the gang database disproportionately features Latinos. In Chicago, a study from February 2017 showed that of the nearly 65,000 people listed in the Chicago Police Department’s gang file, 75% were Black and 21% were Latinos. In July of 2017, a Mexican national living in Chicago, who had been falsely included in the CPD’s gang database, filed a federal lawsuit against the Chicago Police Department. The man, who has lived in the United States since he was five years old, was arrested and faced deportation proceedings because of the CPD’s allegation of gang involvement. As his lawyers at the MacArthur Justice Center argued, “The Chicago Police Department has a policy and practice of falsely labeling young men — almost all of whom are Latino or Black — gang members.” Advocates say that the racial makeup of the Boston database is likely similarly out of whack with the city’s overall demographics.

Local policymakers must act to bring Boston Police policy in line with Sanctuary protections

Policymakers in other cities have taken action to protect their most marginalized residents from discriminatory policing and federal overreach, and Boston should follow their lead. In response to the Trump election, the Mayor of San Francisco cut off cooperation with the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force, upon which agents from DHS’ ICE agency sit. In Portland, Oregon, city leaders responded to a reporter’s inquiries about that city’s gang database, and specifically its racial makeup, by shutting down the database for good. Baltimore, meanwhile, shuttered its controversial plainclothes policing unit in 2017.

Boston’s leaders should take a close look at our own police department’s gang databasing system, and at the BPD’s policies governing information sharing with federal agencies. Among the questions local leaders should ask the police: What kind of department approval, if any, must ICE agents get before accessing the gang database? How many times have ICE agents accessed the database in recent years? What is the racial makeup of the database? Is there any evidence the gang database has led to a decrease in violence? How many people included in the database have never been arrested on suspicion of committing a violent crime? How can someone learn if they are in the database? And what, if anything, can they do to get their name removed if they think they’ve been wrongfully accused? Finally, how is information from Boston School Police officers making its way into ICE’s hands, and enabling the deportations of BPS students?

If Boston’s leaders truly want to protect the city’s most marginalized residents from Trump’s deportation force, they need to get these questions answered as soon as possible, and then act accordingly. Doing so will serve the dual purpose of helping the city engage in a long-deferred conversation about the role of gang databases in BPD policing, with an eye towards protecting young immigrants from the long arm of Trump’s ICE — as well as addressing racial disparities that impact not just immigrants but also African Americans. We know young people are more likely to be system involved if they are listed in a gang database, a problem that has long predominately impacted Black youth. Our Black and Brown youth deserve to be treated better.

Boston’s mayor and local media have of late been publicly soul-searching about the role racism plays in our city. We cannot meaningfully address anti-Black and Brown racism, or truly protect immigrants, if we don’t confront the role the Boston Police Department’s gang database plays in the lives of young people of color in our city.