Fremont Police Said a Man Wielded a Deadly Weapon When They Shot Him. But Records Reveal He Waved a Tent Pole.

The police union’s newly elected vice president led the investigation into the shooting that cleared Officer William Gourley of any wrongdoing.

On May 29, 2017, Rolonte Simril was wandering the parking lot of a busy shopping center in Fremont, California, waving what witnesses and police described as a “metal pipe.”

As Simril muttered to himself, he swung the object as if he was playing baseball, or sword fighting an invisible opponent. It was behavior that unnerved several shoppers. One witness described him as a “San Francisco crackhead,” while another called him a “typical Fremont crazy person.” A third person said Simril was “threatening to hurt people,” and flagged down a Fremont police officer.

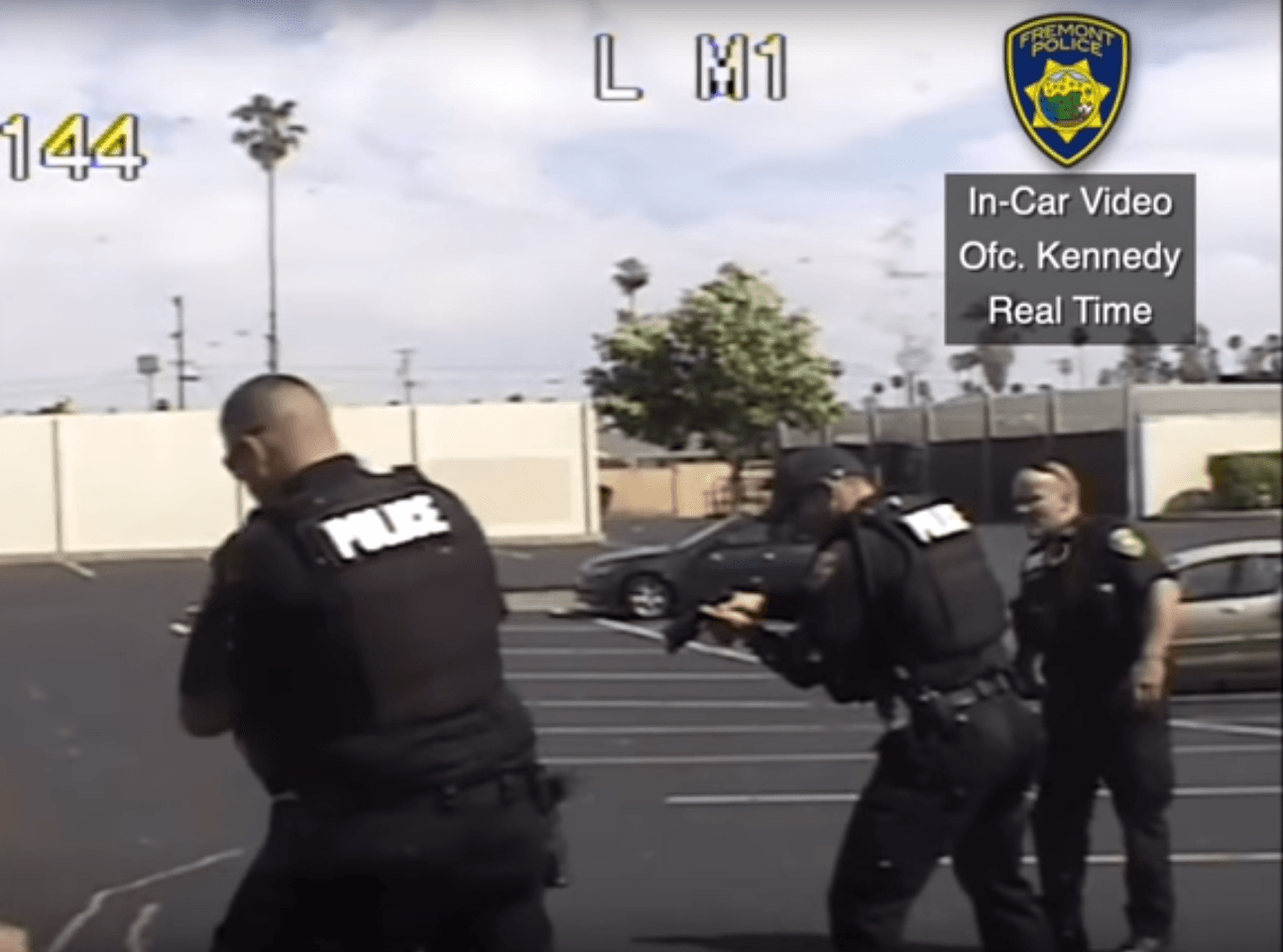

The officer, William Gourley, got out of his patrol vehicle and chased Simril through the shopping center parking lot. A private citizen, meanwhile, followed them in his car and cut off Simril’s path of escape, which caused him to collide with the hood of the vehicle. Cornered, Simril turned and faced Gourley. Gourley then ordered Simril to drop the “weapon” and shot him three times, twice in his abdomen and once in his right thigh.

Simril recovered after undergoing surgery on his gunshot wounds, and Fremont police recommended that he be charged with resisting arrest and brandishing a deadly weapon.

Months later, two separate Fremont police investigations concluded that Gourley’s actions were lawful and within the department’s use of force policy. But crucial details about the incident, including investigative records and witness interviews, were kept secret.

This month, in response to a public records request from The Appeal, the city of Fremont released its investigative reports about the shooting. The documents show that although some people perceived Simril as a possible danger, no one said he attacked anyone before the shooting.

The “pipe” that Simril allegedly brandished was not a deadly weapon but instead a hollow aluminum tent pole. Simril, a 27-year-old Oakland resident, was homeless; after he was shot, police found in his backpack a copy of a May 26 order from the city of Oakland to vacate an encampment.

Although Gourley said in his interview with police investigators that Simril confronted him in a “fighting stance” while holding up the “pipe,” most witnesses said Simril was standing “frozen” still with his arms at his sides when Gourley shot him. There’s no indication in the investigative record that detectives attempted to resolve this inconsistency.

New transparency

Police in Fremont, a midsize city of about 200,000 residents in the San Francisco Bay Area, have historically avoided the intense scrutiny that much larger police departments experience after incidents involving deadly force. But shootings by the city’s officers over the past few years, including the killing of a pregnant 16-year-old in 2017, have led to calls for greater transparency from families of slain people and civil rights attorneys. A new California law that went into effect Jan. 1 made police misconduct records public for the first time, which forced the Fremont police to disclose more information.

Last month, Fremont unveiled a “transparency portal” website that features information about officer-involved shootings. But the department’s website doesn’t include links to actual investigative reports. Instead, the police department posts press releases, edited videos, and investigative summaries. The day it launched, David Snyder, an attorney who leads the pro-transparency First Amendment Coalition, told KQED that the website was “spin.”

In Simril’s case, the police posted only an “investigative summary” that publicized his criminal record, including drug and burglary charges. The department also posted a press release and a short, edited surveillance video showing Simril in the parking lot before he was shot, and officers responding to the scene afterward. The portal also displayed Simril’s mugshot, and photos of the tent pole, as well as of Simril lying wounded on the pavement.

The investigative records released to The Appeal by the Fremont city attorney were not posted on the portal, but they provide a glimpse into the city’s secretive system for investigating officer-involved shootings.

Inconsistent statements

Police Detective Michael Gebhardt was assigned to determine whether Gourley violated the law when he shot Simril. His 92-page report concluded that Gourley’s actions were lawful. Gebhardt based his findings mainly on Gourley’s statement to investigators that Simril was in a “fighting stance” with his “hands up in front of him” making a “quick little movement” while holding the tent pole that caused Gourley to fear for his life. Under a 1985 Supreme Court decision, police can use deadly force when they have reason to believe that the person they are attempting to arrest poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others.

Gebhardt cited interviews conducted by Fremont officers with 18 witnesses, but because there was no video of the shooting he could not conclusively determine if Gourley’s statements were truthful. According to the records obtained by The Appeal, however, most of the 18 witnesses did not say that Simril took up a fighting stance or made threatening motions toward Gourley.

Two witnesses told investigators that they were sitting in a van when they saw Gourley chase Simril through the parking lot and shoot him as he stood still. “[Simril] did not make any movements toward the officer or do anything prior to the shooting,” one witness said in a statement summarized by an officer.

The two witnesses with the best view of the shooting—the person who used his car to block Simril’s path of escape, and his girlfriend who was a passenger in the car—both told the police they didn’t see Simril raise the tent pole or advance toward Gourley.

The man told investigators that while Simril wandered around the parking lot, he yelled gibberish and swung the tent pole but “was not swinging it towards anyone and no one was nearby.” He said that after he used his car to block Simril’s escape, Simril faced Officer Gourley and “kept his arms down along his side and did not say or do anything.”

The officer who interviewed the man just after the shooting wrote in a report that he said, “the officer was about 10 feet away from [Simril] but [Simril] did not motion towards the officer. The officer then shot three rounds, dropping [Simril] to the ground.” He further told the interviewing officer that “he was shocked by the course of action the officer [Gourley] took.”

His passenger told a Fremont detective “[Simril] was not threatening anyone specifically at that time she saw him.” She said that after her boyfriend used his car to block Simril’s path, Simril’s hands “were lowered at his side, and that he appeared ‘frozen,’” and that he “was not flexed, nor relaxed, and just appeared to be standing frozen (as if from fear) facing the Officer.”

Gebhardt chose to accept Gourley’s statement, which conflicted with accounts from multiple eyewitnesses.

Captain Fred Bobbitt, who oversees the Fremont Police Department’s investigations of officer-involved shootings, said in an interview that he is comfortable with the thoroughness of Gebhardt’s work and that witnesses often recall events differently.

“As a result of reviewing surveillance, the reporting party’s information, the witnesses, the officer’s statement, the suspect’s statement, as a result of all of that, it was determined that the force that Officer Gourley used was justified,” said Bobbitt.

He added that Simril was given several chances to make a statement to police investigators about the events leading up to his shooting, but declined to do so.

According to Gebhardt’s report, the police gave him two opportunities to make a statement, first in the ambulance just after he was shot, and two days later as he was recovering from surgery in the hospital.

Potential conflict of interest

Two weeks before the shooting, Gebhardt was elected vice president of the Fremont Police Association, which defends officers who are accused of misconduct or criminal violations. Gebhardt had also previously served as the police union’s secretary, according to public records. In his report about the Simril shooting, Gebhardt acknowledged his position at the police union. He also explained that at the time of the shooting the sergeant in charge of police department’s Crimes Against Persons Unit, which normally investigates officer-involved shootings, was out of state, as was his partner, therefore he “assumed the role of lead investigator into the incident.”

In response to an emailed request for comment on the case, Gebhardt wrote that he was on vacation and could not answer any questions. His supervisor, Captain Bobbitt, said there was no conflict of interest and that investigators are first and foremost police officers dedicated to finding the truth. He added that it’s not uncommon for elected board members of the police union to occupy roles in which they investigate potential wrongdoing by other officers.

“I spent years as an officer-involved shooting detective,” said Bobbitt, “and I was also a board member [of the Fremont Police Association].”

After he arrived at the scene of the shooting, Gebhardt’s first call was to Fremont Police Association president Jeremy Miskella, to notify him that Gourley shot someone. Miskella was also newly elected to his leadership position in the union and had been involved in a shooting. In March 2017, two months before Gourley shot Simril, Miskella and another Fremont officer shot and killed Elena Mondragon, the pregnant 16-year-old. The Fremont police continue to withhold investigative records of this incident. In February 2018, the Alameda County district attorney ruled this killing justified, but the family has filed a civil rights lawsuit in federal court.

After placing the call to Miskella, Gebhardt called the DA’s office so its investigators could begin an independent inquiry. But Simril survived, so the office never conducted a separate review because its policy is to investigate only fatal officer-involved shootings. In November2017, the Fremont Police Association contributed $10,000 to District Attorney Nancy O’Malley’s re-election campaign.

Gebhardt’s last call that day was to the law firm that represents the Fremont Police Association.

He also acknowledged in his report that he had prior contacts with Simril. In 2007, he arrested Simril, then a teenanger, after he spotted him wearing the uniform given to detainees in Alameda County’s juvenile hall. The officer stopped Simril because he had recently escaped from the facility.

The second investigation of the Simril shooting was conducted by the Fremont police internal affairs unit. The eight-page report, included only one page of text and also primarily relied on Gourley’s assertion that Simril “made a movement towards him in close proximity while holding the metal object.” Like Gebhardt, internal affairs investigators also did not appear to have re-interviewed any witnesses whose statements conflicted with Gourley’s.

Although Gourley said Simril threatened to attack him with the tent pole, the DA didn’t charge Simril with brandishing a weapon and resisting arrest as the police first recommended.