Freddie Gray, Five Years Later

On the anniversary of the Baltimore Uprising protests, new evidence in Gray’s death uncovers suppressed witness accounts of police brutality.

This article includes photographs that some readers may find disturbing.

On April 12, 2015, Freddie Carlos Gray Jr. was arrested in the Gilmor Homes housing development in West Baltimore by three officers on bike patrol. Less than an hour later, a medic was called to the Western District police station, where Gray, 25, was unconscious and not breathing. On April 19, Gray died from complications due to a cervical spine injury.

Baltimore resident Kevin Moore captured some of Gray’s arrest on video that was widely shared. The video showed Gray screaming as he was restrained on his belly by a heavyset bike officer, Garrett Miller, and then loaded into a police transport van, his legs dragging. “I hear the screams every night,” Moore later said. “‘I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I need help, I need medical attention.’ This is the shit that play in my mind over and over again.”

Gray’s in-custody death came nearly a year after Staten Island resident Ramsey Orta filmed NYPD officers dragging 43-year-old Eric Garner to the ground and placing him in a chokehold as Garner said repeatedly “I can’t breathe.” And like Garner, the death of Gray spurred large protests that became known as the Baltimore Uprising.

At a press conference the day after Gray died, the Baltimore Police Department revealed that the transport van that picked him up made several stops, including to pick up another prisoner. Deputy Commissioner Jerry Rodriguez also insisted, “We have no evidence—physical or video or statements—of any use of force.”

On May 1, street protests turned into celebrations when State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby filed charges against six officers in Gray’s death. The charges—ranging from misconduct in office to manslaughter and second-degree depraved-heart murder—pertained to the officers’ failure to put Gray in a seatbelt or call for timely medical assistance. In September 2015, Baltimore reached a $6.4 million settlement with Gray’s family. But Mosby’s cases ended up failing in criminal court. After one mistrial and three acquittals on all charges, Mosby dropped charges against the remaining three officers in July 2016.

Gray joined a long line of high-profile Black victims of police misconduct, like Walter Scott, who was shot to death by Michael Slager in April 2015 after he fled from Slager during a traffic stop in South Carolina. Like Gray and Garner, a bystander captured the Scott incident on video. Gray quickly became a touchstone for the then-emergent Black Lives Matter movement, but for the public his death has largely remained a mystery.

The Appeal obtained evidence from the discovery file in the criminal case against the officers that, along with the police department’s Internal Affairs investigation, sheds light on what occurred during Gray’s arrest. The evidence includes video and audio interviews conducted by investigators with eyewitnesses, officers, and medics, as well as the police department’s full Internal Affairs investigation.

The new files reveal numerous unreported eyewitness accounts of force by officers, particularly at the van’s second stop. Witnesses told investigators that they saw Gray thrown headfirst into the van at that stop. Several witnesses also described him becoming quiet and motionless at this stop, after screaming loudly for several minutes.

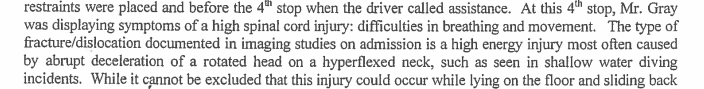

According to the autopsy report, Gray’s fatal injury, usually seen in “shallow water diving incidents,” was caused by a “high-energy” impact of his head against a hard surface.

But the medical examiner testified in court that she relied on the accounts of police officers, who were the primary suspects in the case, to make her conclusions about when and how Gray died. She made no mention of any civilian witnesses to force in her autopsy report or trial testimony. She also said the state’s attorney’s office determined which statements she received.The newly obtained evidence supports and broadens the investigation that journalist Amelia McDonell-Parry and I conducted into Gray’s death for the 2017 podcast “Undisclosed: The Killing of Freddie Gray.”

STOP ONE: GRAY’S ARREST

Kevin Moore’s video brought international attention to Gray’s arrest on Presbury Street in West Baltimore, which became known as “stop one” of the police van’s six-stop journey. But the new files reveal that throughout April 2015, police and prosecutors took numerous statements from eyewitnesses who reported accounts of excessive force before Moore started filming. With some variations in their accounts, these witnesses described officers forcefully restraining Gray, putting a knee into his upper back, and dragging him aggressively across the concrete.

And Gray’s body showed signs of trauma, including a fresh-looking wound on his shoulder that was never accounted for or investigated by police:

Some witnesses also described Gray being beaten and/or shot with a Taser during his initial arrest. Moore can be heard on his own video screaming, “That was after they tased the fuck out of him.”

Despite Gray’s apparent physical distress during stop one, police, prosecutors, and the medical examiner ruled out the possibility that he had been fatally injured during his arrest. They pointed to his ability to lift his neck, speak, and bear weight on his legs when entering the van in Moore’s video. Although the Gray family spoke out in April 2015 about other injuries—including three broken vertebrae and a crushed voice box—they were never documented in any of the hospital or autopsy reports. One member of the family’s legal team later walked back certainty about those claims.

Gray’s specific type of fatal injury, a “jumped facet” of his C4 and C5 cervical spine, was caused by an “abrupt deceleration” of his rotated head against a hard surface, according to the autopsy. Even Officer Miller, who weighed 240 pounds, could not cause that specific injury by putting pressure on Gray’s spine from above, according to Dr. Leigh Hlavaty, professor of pathology at the University of Michigan. “Even if Freddie had his head down and turned to the side, the knee to the back of the neck was not going to be the force to create this jump lock facet type of fracture,” she explained on the “Undisclosed” podcast.

Because the physical evidence did not support the theory that Gray was fatally injured at stop one, police and prosecutors dismissed the significance of any injury at the stop. Ultimately, Moore’s video produced opposing results: It drew attention to Gray’s story and the possibility of excessive force, and it helped the police divert attention from what happened at the next stop.

STOP TWO: AROUND THE CORNER

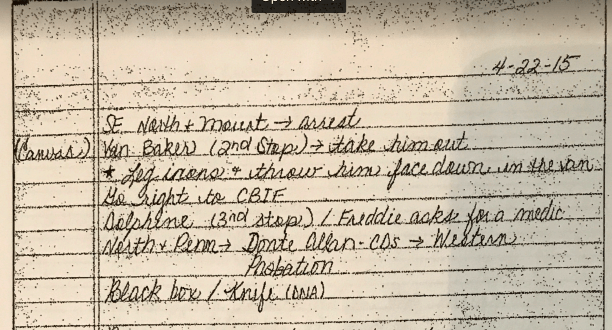

According to the police, Lieutenant Brian Rice and the other bike officers decided to send Gray directly to Central Booking rather than question him at the station. After stop one, they met up with the van driver around the corner, at Mount and Baker streets, to complete the arrest process away from the crowd of observers. There, officers shackled Gray’s ankles.

Gray can be heard screaming on the van driver’s dispatch call between stops one and two, and the accounts that witnesses provided to investigators about stop two are consistent. These stories mostly went unreported by the media, leaving a piece of the history of what happened to Gray out of the public narrative.

Moore, who took the cell phone video of stop one, was the first witness to report to police about stop two. He did so mere hours after Gray’s arrest.

“When they stopped down on Baker Street, and when I tell you dude, I wish I could’ve recorded it,” he told detectives. “They pulled him out the paddy wagon, tased him again, and then threw him back in.” He clarified this later: “They lift him up, wet noodle, throw him in the back of the paddy wagon.”

“Feet first or headfirst?” one detective asked.

“Headfirst,” Moore responded.

Moore told detectives that one officer threatened him and other witnesses: “You’d better get the F away from here,” he reported the officer saying. “Jail, jail, jail.”

The detectives pressed Moore for details about the alleged Taser shooting.

“They got the prongs that shoot out,” Moore said, gesturing toward his right knee. “They’re on him. You know?”

“You can physically see the prongs?” the detective asked.

“I can physically see the prongs in his leg,” Moore answered.

Baltimore police officials denied that Gray was ever shot with a Taser. During the April 20 press conference, Deputy Commissioner Rodriguez said that there was no evidence of any use of a Taser, neither “physical nor any of the statements.” But Moore provided his statement about Gray’s alleged tasing on April 12.

As McDonell-Parry reported on the “Undisclosed” podcast, pictures of Gray’s body from the hospital show what could be Taser marks under his right knee.

The medical examiner, however, offered no explanation of these marks’ origin.

Similarly, in an April 21 interview, Duane Day, a childhood friend of Gray, told investigators that he “watched them tase him two times, in handcuffs” during stops one and two. Day said that he left stop two on his bike after seeing that.

On April 13—the day after Gray’s arrest—his friend Brandon Ross went to police headquarters and said he ran to help Gray after hearing him screaming and being shot with a Taser during stop two. “Freddie is laying in the gutter with three officers around him. He’s screaming,” Ross told the police. “And they pick him up again and threw him headfirst, threw him in the wagon.” Indeed, after stop two Ross called 911 to report an “assault” by police.

Ross recorded some of what he witnessed during this stop on a cell phone he borrowed from his neighbor, Michelle Gross, and shared it with investigators. The police did not disclose Ross’s video to the public. On May 20, 2015, the Baltimore Sun shared a part of it after receiving a copy from Gross. The full video was played later in court during all four of the officers’ trials.

Ross’s video is jumpy. It shows about 15 seconds of Gray, silent and motionless, hanging off the edge of the van, his knees on the ground, surrounded by officers. Rice enters the van. Officer Edward Nero picks up Gray’s legs and helps load him into the van. Officer William Porter approaches from his nearby car.

About halfway through Ross’s video, it cuts to black, but the audio continues to record. One of the officers is heard yelling, “Jail, jail, jail,” as Moore had reported.

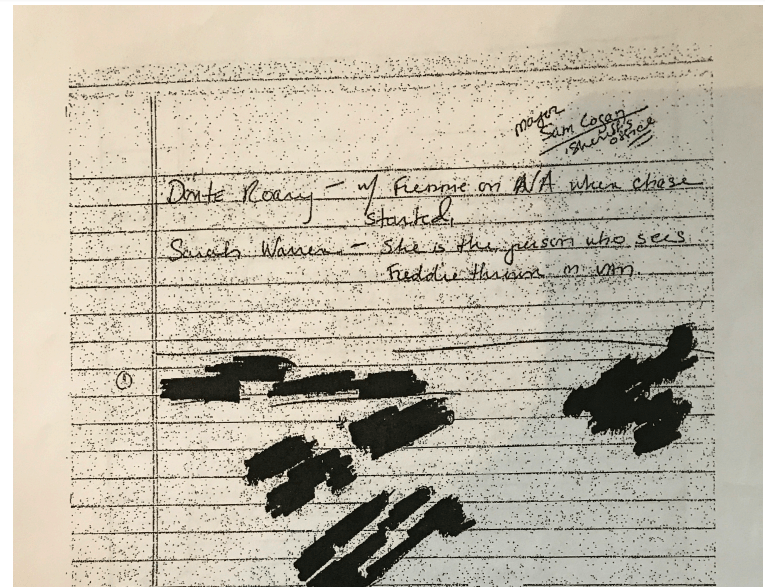

Several additional witnesses observed stop two from their Gilmor Homes apartments. Sierria Warren, interviewed by detectives outside of her home on the afternoon of Gray’s arrest, described her and her daughter being awakened by Gray’s screams. She heard eyewitnesses accuse the officers of tasing him.

Warren said Gray was lying “on his stomach, face down” when officers shackled his ankles. Then, she said, “they just threw him in back [of] the paddy wagon, like really threw him in the back.” Warren repeated this statement a few times, calling it “aggressive.” She also heard one officer threaten to tase a civilian.

Detectives never asked Warren to come to headquarters to provide a videotaped statement, but notes from the state’s attorney’s office obtained by The Appeal indicate that prosecutors knew about her story. A spokesperson for the state’s attorney’s office did not respond to requests for comment from The Appeal.

On April 14, Kiona Craddock met with an investigator from the state’s attorney’s office, after her own video of Gray’s arrest had appeared in a local news report. Craddock told the investigator that she returned to her house after stop one, heard more yelling, and looked outside.

Gray “was on the ground, they threw him in the paddy wagon face down,” she said. “When they threw him in that paddy wagon, he looked limp. He wasn’t screaming no more either.”

Jacqueline Jackson also witnessed stop two from her apartment window. Jackson shared her story with the “Undisclosed” podcast in 2017.

“When I looked out the window, I seen they had Mr. Gray. … They threw him up in the paddy wagon headfirst.” She said she heard a noise, like a thump, followed by Gray making “moaning” sounds. “After it happened, they looked scared,” she said of the police. “All of them looked scared.”

Jackson was the only stop two witness to convey the belief that she had witnessed Gray’s fatal injury: “And so when they put him up there, they didn’t put him up there. They threw him headfirst. That’s how he got all the injuries.”

Jackson also shared this stop two account with a few reporters, but it never got picked up broadly. On April 24, she told the Baltimore Sun that she saw Gray’s head hanging down when he was thrown. According to the medical examiner, Dr. Carol Allan, Gray’s “jumped facet” injury happened when his neck was “hyperflexed,” or bent forward.

Earl Williams also appeared in the April 24 Baltimore Sun report: “They picked him up and literally threw him back in the wagon,” he said. “You know, that’s crazy.”

Jamel Baker observed stop two from his apartment on the other side of Mount Street. He was right above the van when he heard a scream.

“I heard something that sounded like someone was being killed,” he told police investigators on April 12. “That man sounded like he was dying.” Baker was not as clear as the other witnesses as to how Gray was put back into the van: “They’re like picking him up off the ground and throwing him—like, putting him in the wagon,” he said.

Today, Baker doesn’t have a clear memory of that part of the story, but he still remembers Gray’s screams. “I heard screams, probably like two screams,” he told The Appeal. “When I went to the window, after that, I heard no more. When they put him in the van, I ain’t hear no more screams.”

Finally, two more witnesses, Jernita Stackhouse and Tobias Sellers, observed stop two from the corner of Presbury and Mount. Both told the “Undisclosed” podcast in 2017 that they saw Gray thrown into the wagon—”like he was a dang rag doll” Sellers said. Sellers also spoke with police investigators on April 22, 2015, when he described Gray being beaten with batons at stop two and tased.

If the witnesses’ statements were accurate, then it would seem that Ross’s video captured the aftermath of Gray being thrown into the van. This would mean that Gray was put into the van twice—thrown in and then pulled in. The van’s passenger space was narrow, measuring 19 inches across on the floor, according to case documents. It is not known how far Gray was thrown.

In total, there were 11 known witnesses to stop two. Nine reported that Gray was thrown into the van, many saying “headfirst.” Most reported Gray screaming loudly and then becoming quiet and/or motionless at this stop. Police asked three witnesses to give longer videotaped interviews on the record. Prosecutors asked just Ross and Baker to testify in court. Their testimony was mostly limited to identifying Gray in videos. Neither was asked about Gray being thrown headfirst into the van.

The prosecution’s case was that Gray was still alive and well leaving stop two, based on the autopsy report. To support this claim, prosecutors actively disputed claims that Gray was injured during the first two stops during the four trials. While ostensibly holding the officers accountable in Gray’s death, the state relied mostly on what law enforcement said that morning.

STOP TWO: ACCORDING TO THE POLICE

Over four trials, the officers present at stop two offered consistent accounts about what happened there: Rice and Miller pulled Gray out of the van, Miller shackled his ankles, and Gray acted like a “dead fish” in order to resist arrest. Rice pulled Gray into the van, and Nero helped by lifting his legs. Then, the officers laid Gray flat on the van’s floor and closed its doors. Each officer testified that Gray then suddenly got up and started banging, yelling, and shaking the van back and forth, despite being shackled at the hands and feet.

But the accounts presented by officers in court changed significantly from what they told investigators during the afternoon of Gray’s arrest. Their original stories were not consistent and did not include what Ross’s video showed: Gray’s motionless body hanging out of the van.

The officers’ first-day statements were especially contradictory and confusing about how they put Gray back into the van—notable, given the clarity of witness claims that he was thrown. “We lifted him up and actually put him back up into the wagon,” Lt. Rice said. Nero said that all of the officers worked together to “push” Gray in the van. Miller believed that Rice pulled him in alone. Meanwhile, Officer Zachary Novak couldn’t even remember if he got out of his police vehicle at stop two.

Officer Porter, interviewed a few days later, struggled with whether Gray was pushed or pulled into the wagon and by whom. He could only remember that it was a “skinny white guy.” His story changed mid-interview.

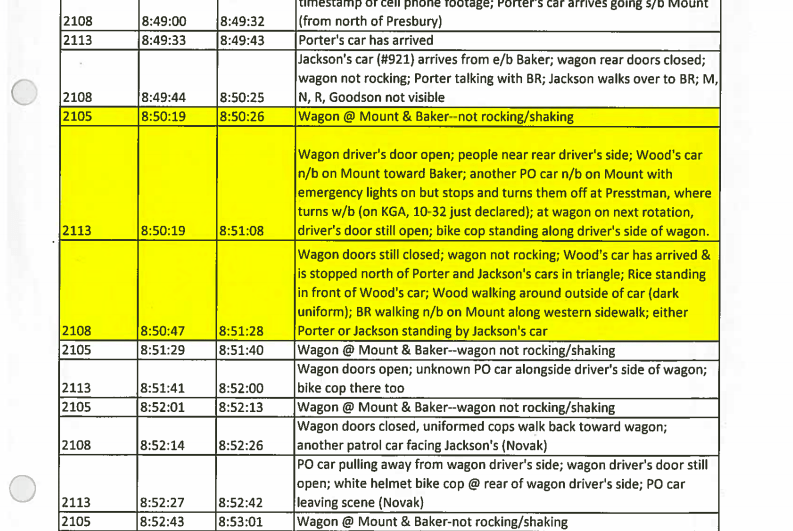

Lt. Rice’s account of Gray’s arrest differed most starkly from the other officers. He said that Gray was “shaking the van violently” throughout stops one and two. Miller mentioned the shaking, but only at the end of stop two.

Rice’s account was important, because the van-shaking story became a pillar of the Freddie Gray case narrative. The shaking, which only Rice had reported, is mentioned in the autopsy report as occurring throughout stops one and two. It became the defense’s story in court for how stop two concluded, repeated by all of the officers present at the scene. It also became central to the media narrative about the case.

But Rice’s van-shaking story was not corroborated by any civilian witnesses. An Internal Affairs investigation, launched after the criminal charges were dismissed and outsourced to two Maryland county police departments, reviewed all of the closed-circuit television (CCTV) footage and noted “wagon not rocking/shaking” at each moment.

During his first-day interview, Rice also repeatedly said that Gray was “hitting his head” against the van walls after the doors were closed at stop two. “When he got back into the wagon, the wagon began shaking violently, and he was hitting his head, and kicking the door,” he said.

But Rice’s account of Gray’s head striking the van’s walls never made it to trial. It wasn’t supported by the physical evidence: Gray’s head only had one point of major impact, not surface injuries. His cause of death did involve a high-impact injury to his head, though.

Officer Novak also offered this story as a possibility to investigators: “We’ve had people in the past, like, when they’re upset hit their head up against a wall.” He suggested that the Crime Scene Unit examine the wall of the van: “It wasn’t like a lot of blood or anything like that, but it was like two smears.”

Novak was at the Western District station when the medics arrived on April 12. Angelique Herbert, the lead medic, told investigators that she asked the officers what happened and that the “white officer” on the scene—Novak—responded, “I don’t know, but I think he was banging his head up in the paddy wagon.”

Investigators heard this account one more time on April 12 from Donta Allen, who was a passenger in the van with Gray. The bike officers had placed Allen on the other side of a metal partition from Gray at stop five, the last stop before the Western District. Allen told investigators, “It sounded like he was banging his head against the metal, like he was trying to knock himself out or something.”

In media interviews, Allen later changed his statement, saying that he only heard “light banging.” During the July 2016 trial of Officer Goodson, he also testified that he had spoken to Novak before his interrogation and that the officer had given him the fake name “Danny” to put in his phone. Novak received immunity from prosecution by the state.

During Goodson’s trial, Judge Barry G. Williams scolded prosecutors for failing to turn over to the defense evidence of two private meetings they held with Allen. “I’m not saying you did anything nefariously,” Williams said. “I’m saying you don’t know what exculpatory means.”

The story that Allen heard Gray banging his head in the police van was repeated throughout the media. But the public never learned that Lt. Rice was a primary source. The prosecutors never played Rice’s taped statement during his own trial, as they had during the other officers’ trials.

Prosecutors largely did not hold the officers accountable for their confused and changed stories about stop two. The state’s case was based on the autopsy, which determined that Gray was fatally injured sometime between stops two and four while the van was in motion. Dr. Allan’s report, however, was not conclusive: “Therefore, the time the injury most likely occurred was after the 2nd but before the 4th stop of the van, and possibly before the 3rd stop,” she wrote.

THE WITNESSES

At least 15 civilians reported that Gray was the victim of excessive force by the Baltimore police. Many of the witnesses were elderly residents of row houses across the street from Gilmor Homes. Their accounts were consistent; they can also be seen on CCTV cameras that recorded Gray’s arrest, which definitively places them at the scene. But, at most, they were interviewed for a few minutes outside their homes and forgotten.

Some of the witnesses say they remain frustrated by the investigative process. “They asked a few questions, but they act like they didn’t believe what I was saying.” Alethea Booze, who witnessed stop one, told The Appeal. “Everyone that saw what happened wanted to appear in court, but they didn’t call any of us.”

Five years later, Baker, who did appear in court, still feels let down by the prosecutors. “They made it seem like we was going to get justice, but nothing really happened,” he told The Appeal. He described the trials as “a waste of time.”

When the police department officially closed the Gray case in 2017, it released several binders of documents and photographs to the Baltimore Sun in response to a Public Information Act request. (The Sun has since removed the documents from its website.)

The newly obtained evidence reveals that significant pieces of the case were not included in the police’s 2017 release. The binders included official transcripts from officers’ statements but none from any civilian witnesses. Witnesses were reduced to mugshots, criminal histories, and scant notes by investigators. The 2017 release represented the police’s final word on the Gray case, but it mirrored the department’s investigation, which suppressed witness statements and minimized the lived experiences of people in the Gilmor Homes community.

Amelia McDonell-Parry contributed to this story.