FOSTA Backers to Sex Workers: Your Work Can Never Be Safe

On April 11, President Trump signed the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA), legislation that would make it possible to hold the operators of websites criminally and civilly liable if third parties were found to have posted advertisements for prostitution. Days before the legislation was enacted, however, federal authorities seized Backpage.com, essentially locking sex […]

On April 11, President Trump signed the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA), legislation that would make it possible to hold the operators of websites criminally and civilly liable if third parties were found to have posted advertisements for prostitution.

Days before the legislation was enacted, however, federal authorities seized Backpage.com, essentially locking sex workers out of the website. The United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Arizona indicted seven Backpage staffers, including co-founders James Larkin and Michael Lacey, on charges including money laundering and facilitating prostitution. Then, on April 12, the Department of Justice announced that Backpage CEO Carl Ferrer pleaded to federal charges related to money laundering and violating the Travel Act to facilitate prostitution, contingent on pleading to state trafficking charges.

FOSTA and the Backpage indictment have rapidly transformed trafficking into a matter of national politics. On April 19 Trump declared in characteristic overstatement that “human trafficking is worse than it’s ever been in the history of the world.” The very same day, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, who is thought to be considering a run for president in 2020, announced plans to change the state’s trafficking laws by “eliminating proof of the elements of force, fraud or coercion in cases of children under 18.” Trafficking, Cuomo said, “is nothing short of a modern day slave trade that preys on children and the most vulnerable among us, and it must be shut down once and for all in New York and beyond.”

Prior to FOSTA’s passage, sex workers and survivors of trafficking, as well as advocates for both communities, warned that the legislation and crackdowns on websites that could come in its wake would be dangerous for sex workers and survivors of trafficking alike. They argued that closing low-cost online ad sites like Backpage would drive sex workers out of indoor work spaces that allowed for discreet advertising and client screening and into the streets.

Sex workers also said that low-income sex workers, sex workers of color, and trans sex workers — already facing high levels of arrest and violence — would be disproportionately affected by the loss of sites like Backpage. Indeed, within 48 hours of the feds’ seizure of the website, sex workers reported a drastic loss of income, the threat of homelessness, and the opportunistic return of abusive customers.

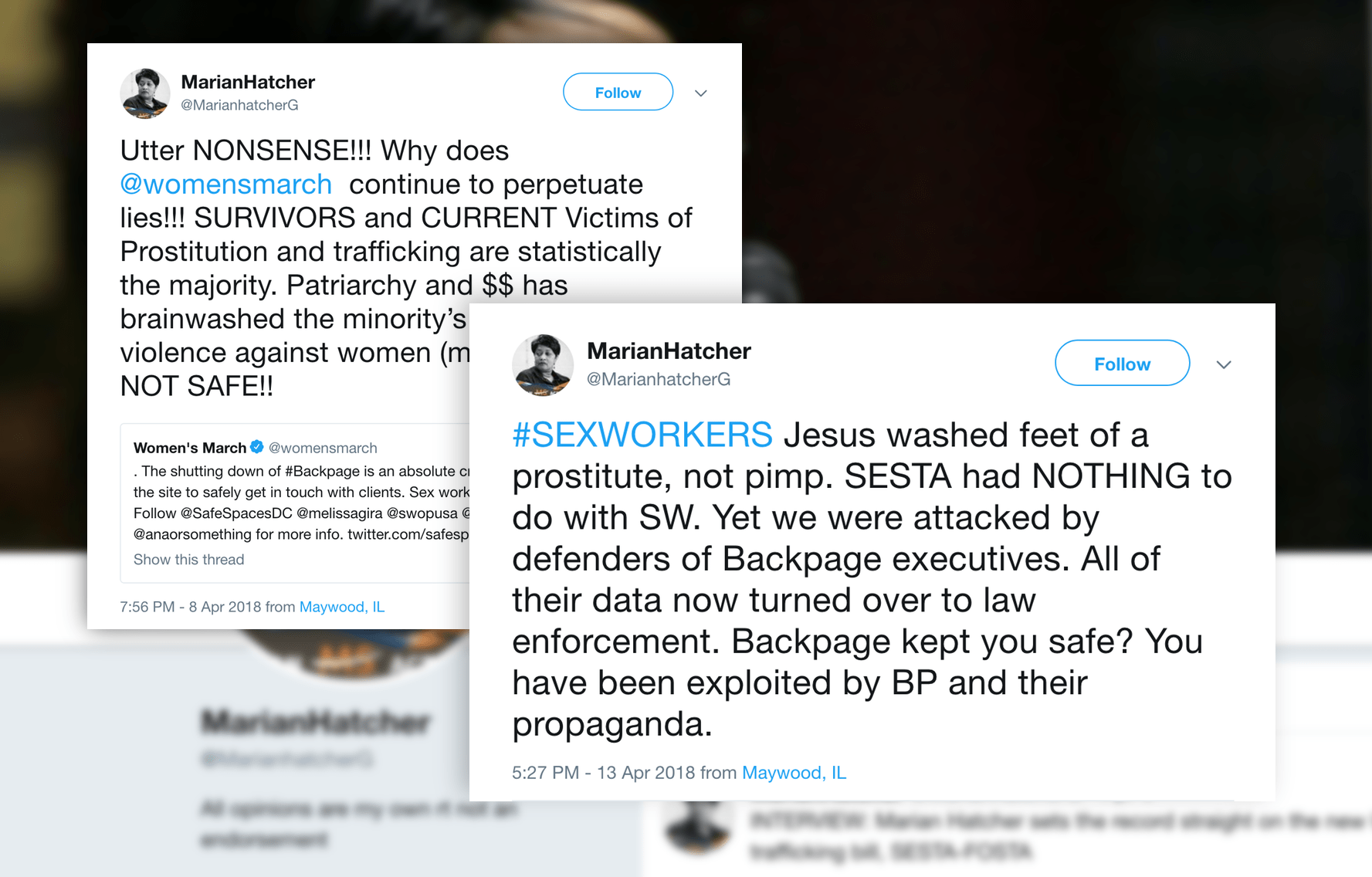

Since FOSTA was enacted, the groups that pushed for its passage — among them law enforcement, anti-sex work groups, and religious right groups — have acknowledged the vocal opposition to the legislation from sex workers themselves. Marian Hatcher, the senior project manager and human trafficking coordinator at the Cook County Sheriff’s Office, who lobbied in favor of the legislation, tweeted on April 13, “#SEXWORKERS … SESTA had NOTHING to do with SW.”

Hatcher and other high-profile FOSTA supporters continue to maintain, however, that there are no safe places for sex workers. Republican Senator for Ohio Rob Portman, who drafted the original bill on which FOSTA was based, was asked about sex workers’ safety; a spokesperson responded, “Tell that to the mothers and fathers of daughters who’ve been murdered after being trafficked on Backpage.” Similarly, in an April 5 interview meant to “set the record straight” on a “new anti-trafficking bill in the US [that] has gotten a lot of bad press,” Hatcher said, “screening for potentially violent sex buyers and assurances of safe places do not exist in prostitution.”

But Hatcher and Portman’s rejection of the idea that online ads can be a form of harm reduction is disputed by sex workers and researchers alike. A 2017 University of Leicester study of online sex workers showed that 85 percent of respondents who advertised online said this allowed them to screen customers. When asked about violence they had faced in the previous 12 months, just under eight percent had experienced sexual assault, and five percent had experienced physical assault. Research from University of Baylor suggests that the Craigslist Erotic Services’ section led to a 17 percent drop in female homicide rates.

By denying the existence of “safe places” for sex workers on sites like Backpage, Hatcher maintains that sex work can never be safe. Hatcher has also attacked women’s rights groups, like the Women’s March, for stating that sex workers had relied on Backpage to safely contact customers. “Utter NONSENSE!!! Why does @womensmarch continue to perpetuate lies!!!” she tweeted on April 8. “ITS [sic] NOT SAFE!!”

Hatcher’s stance stems in part from her unusual personal history: After a career in corporate America, she says was trafficked on Chicago’s streets while in her 40s. Her path out of the sex trade began with a 2004 arrest for violating probation on a drug charge. “I never expected that jail would be my saving grace,” she wrote in a first-person essay for Vox in 2017. “Now I hope to make it the same for more victims like me.” She has worked for 14 years now in Illinois’ Cook County Sheriff’s Office, at first joining the same program that she credits with saving her from the sex trade. In 2016, she received a Presidential Lifetime Achievement Award for Volunteer Service from former President Barack Obama.

Since joining the sheriff’s office, Hatcher’s work has turned toward policy, she has said, as well as “efforts to bring down pimps, traffickers, and johns.” With Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart, Hatcher coordinates the National Johns Suppression Initiative, claiming more than 600 arrests since its inception. She is also a paid coordinator for Demand Abolition, which has supported public awareness of Cook County’s efforts to disrupt “sex buying,” which the organization believes is the solution to trafficking. And along with Dart and Demand Abolition, Hatcher has also campaigned against Backpage and for FOSTA.

As a leading FOSTA proponent, Hatcher not only supports continued police crackdowns on sex work, but she also advances a political agenda: that consensual sex work does not actually exist. “Prostitution is ugly,” as she put it in 2015. “Most of it is sex trafficking.” After FOSTA was enacted in April, Hatcher said, “To argue that this bill will harm ‘sex workers’ is to ignore the fact that most women and girls being sold on these websites are not doing so by choice.” When websites serving sex workers began to go offline, Hatcher said, those shutdowns were evidence of “the power SESTA-FOSTA has to hold them [websites] legally responsible for facilitating these criminal activities.”

While celebrating the closure of websites proven to provide sex workers with more safety and power at work, Hatcher also dismisses sex workers’ fears — already borne out — that FOSTA would harm them. Such demands for safety are invalid, Hatcher and other FOSTA proponents argue, because sex work itself is illegitimate. “As a survivor of the sex trade and someone who works closely with other women globally, who are either surviving or who have survived it, I unequivocally maintain that prostitution is an inherently violent industry in both illegal and legal environments,” Hatcher told The Appeal. “Websites will never provide safety in prostitution…. The ability to screen sex buyers online is an illusion that must be debunked.”

What is needed, Hatcher has said, is “robust exit services for those who sell sex.” That’s what Hatcher and the Cook County sheriff’s program provide sex workers — along with a criminal record.