Florida Residents Trapped In Substandard Housing Face A New Threat: An Eviction Moratorium Set To Expire In Weeks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed Florida lawmakers’ failure to build affordable housing for its residents.

Miranda’s federal stimulus check wasn’t enough to save her from a mold-infested South Florida apartment. Miranda, whose name has been changed to protect her from a landlord she says is abusive, lives in a small apartment with her four children in Hallandale Beach, Florida, a town in Broward County that sits just north of the Miami-Dade County border. Miranda says her home is full of black mold that’s making her kids sick, and when she reported the conditions to her landlord, he showed up to her apartment and threatened her. Miranda says that instead of remediating the mold, her landlord is now trying to evict her.

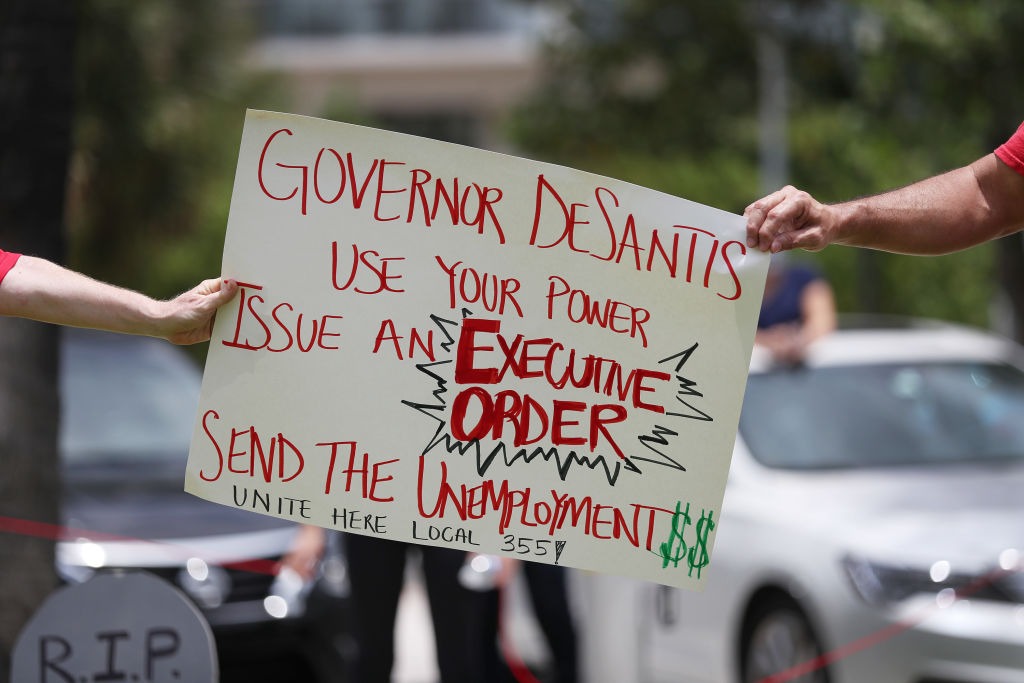

Miranda is one of thousands of Floridians waiting to see if Governor Ron DeSantis will allow the state’s COVID-19 eviction moratorium to expire on July 1, which would force them to survive on the state and federal government’s paltry rental, income, and unemployment assistance.

“The landlord threatens us every day and has posted illegal evictions twice,” Miranda wrote in a GoFundMe fundraiser. “I unfortunately have been unemployed due to Covid and have not had any income besides my stimulus check. I have begged the owner to please return my money so I could move my family somewhere safe and healthy. He refuses to help and said that he does not care and to get the bleep out.”

Last month, Miranda contacted Hallandale Beach Vice Mayor Sabrina Javellana, who pledged to help her. But, barring any further moves from DeSantis, Florida’s eviction moratorium will expire July 1. And in the starkly unequal Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Palm Beach metropolitan area, affordable housing is all but impossible to find. Javellana shared photographs of Miranda’s apartment with The Appeal: They show patches of black mold festering on the walls and in ceiling light fixtures.

“She’s looking for another place, but that’s pretty much where she has to live for now due to her limited finances,” Javellana told The Appeal.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the precarity of Florida renters. Several studies have shown that Miami-area renters are among the most “rent-burdened” people in the United States, and South Florida renters spend a higher share of their incomes on rent than residents of any other major metro area. The tourism and hospitality industries dominate South Florida, both of which have taken a massive hit in the COVID-19-induced recession. Miami-Dade County’s median household income is a scant $59,000, far lower than most major cities. New housing in the area, however, is not built for working-class residents, but for international investors who park—or sometimes even launder—money in real estate. In 2018, local real estate analyst Peter Zalewski estimated that Miami-Dade County had so many million-dollar-plus condo units available that it would take at least four years to sell them all.

South Florida’s political class has resisted calls from activists to force local developers, who donate heavily to county and city governments, to build units priced for local teachers or hospitality workers. In the Miami-Dade County area, politicians have been hostile to building affordable units: In 2016, County Commissioner Javier Souto called affordable-housing laws “social engineering” before voting down a proposal to build homes priced for families making between $29,000 and $67,000 per year. In 2017, the city of Miami Beach admitted that it failed to meet its goal of building 16,000 affordable units between 2011 and 2020, and instead revised its target to a more modest 6,800 units by 2030. A 2017 Urban Institute study found that Miami’s local real estate developers successfully lobbied local lawmakers against enacting any new affordable-housing laws.

Affordability issues plague the entire state: In 2017, the National Low Income Housing Coalition found that Orlando ranked dead-last nationwide in affordable units. But state lawmakers failed to fix Florida’s affordability crisis: In 2017, the Miami Herald reported that state lawmakers had, over 10 years, siphoned more than $1.3 billion from a trust fund set aside to build affordable units statewide. Tallahassee had swept that money into side projects instead, including tax breaks during the Great Recession. Over that last decade, the state lost tens of thousands of publicly subsidized rental units. When Miami finally passed mandatory “inclusionary zoning” regulations on developers in a small section of downtown Miami in 2018 as a test project, state legislators then attempted to discourage any other local governments from enacting similar rules statewide by requiring towns to reimburse developers for the cost of building those affordable units.

The federal government has also failed to act: The Department of Housing and Urban Development has left low-income housing units without air conditioning for years, even though South Florida’s summers are so hot that they constitute a public health risk.

Advocates have repeatedly warned that Miami could face an “onslaught of evictions” if DeSantis lets the moratorium expire.

Now, local lawmakers are scrambling to find solutions to help struggling renters before the eviction ban expires in early July, a moment that also coincides with the end of the additional $600 in weekly unemployment benefits as part of the CARES Act. Miami Beach lawmakers set aside roughly $900,000 for rental assistance amid the pandemic, a paltry sum considering that median rents in many Miami Beach neighborhoods are typically priced at around $2,000 per month. The state-level unemployment website is so broken and ineffectual that it briefly became national news at the beginning of the outbreak. Housing experts predict that Florida will experience a wave of evictions once DeSantis lifts the moratorium: More than 850 evictions have reportedly been filed in Miami-Dade County since March 12. Another 263 evictions are pending in Orange County, which includes Orlando.

With her COVID-19 stimulus check spent, Miranda hopes that her GoFundMe will help her move away from an unhealthy apartment and an abusive landlord. “I can not even open the windows especially at night because this building is infested with flying termites,” she wrote online. “Please help my family and I raise the money to get us out of this situation and into a home that is safe and inhabitable. The money I’m raising includes 1st last and security deposit along with mover fees and all other expenses needed to move. May God bless each one of you that help.”

As of June 2, though, Miranda had received just $50.