Federal monitors go where they’re not wanted: Juvenile Court

Memphis critic says Juvenile Court Judge’s resistance to reforms has ‘emasculated’ Department of Justice

When federal monitors return to Memphis this week to continue their reform efforts at Shelby County Juvenile Court, they’ll be facing off with a judge who doesn’t want them there.

It’s the monitors’ first visit since June, when Shelby County’s top three elected officials, including Juvenile Court Judge Dan Michael, sent a letter to the U.S. Department of Justice. The letter asked Attorney General Jeff Sessions to end the court’s 2012 agreement to overhaul its practices, even though the court is not in full compliance with more than a third of the agreement’s 94 provisions. Sessions has yet to respond to the letter, and the agreement is just that — voluntary and not enforceable by a federal judge.

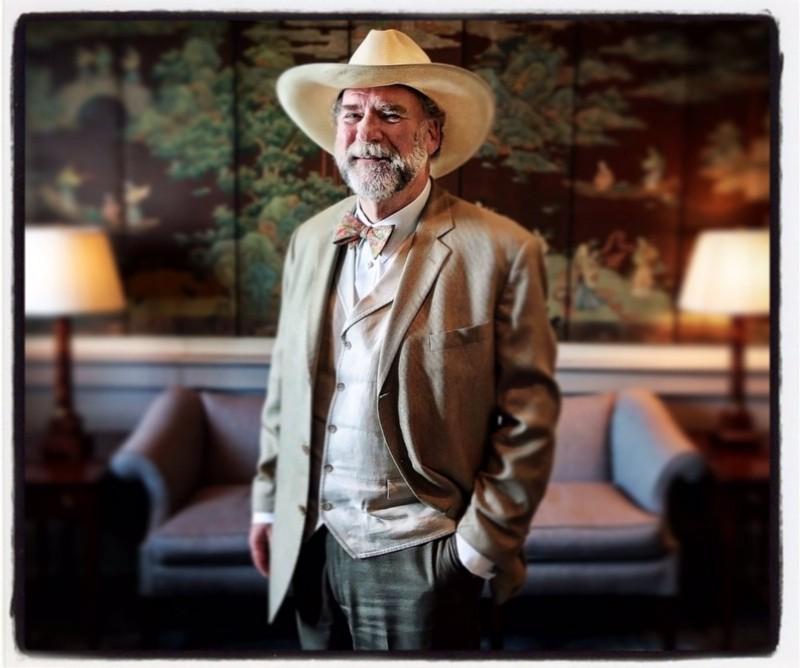

But Michael, who is sometimes pictured wearing a bolo tie and a cowboy hat, has made no secret of his disdain for federal intervention, not unlike his Southern politician predecessors who stood in schoolhouse doors rather than integrate public schools.

During a TV interview in September, Michael lit into two of the three monitors and accused the DOJ of creating a racial “firestorm” because of repeated findings that the court treats black children more harshly than similarly accused white children.

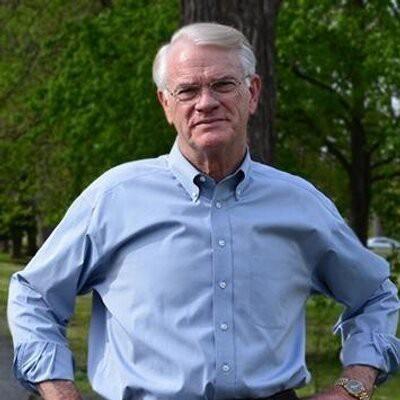

Michael’s remarks undermined the court’s attempts to rehabilitate itself, said Bill Powell, who quit his job as the settlement agreement coordinator when he learned about the letter, which was also signed Shelby County Sheriff Bill Oldham and Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell.

“When the mayor signed off on that letter, I felt like I was standing alone,” said Powell, who has worked more closely than anyone with federal monitors who’ve visited the court at least twice a year since 2013. “It took the legs out from under me.

“Everybody down there at Juvenile Court has their boss on record saying, ‘We have done enough, this should be terminated,’ ” Powell said. “They’re not feeling that urgency, and they’re going to feel like this stuff is trumped up — pardon the expression. The DOJ has been completely emasculated.”

And although the number of children detained by Juvenile Court has fallen sharply in recent years, mirroring the national trend identified by the Sentencing Project, the pattern of racial disparity hasn’t budged.

“Kids who are in the same circumstances are having different outcomes and the only factor for this difference is race,” Powell said.

In a county that is majority African-American, the disparity spells disaster for children of color, threatening to trap them in an unjust system in a state that birthed the for-profit prison industry. Corrections Corporation of America, which has since renamed itself CoreCivic, started in Tennessee in the early 1980s; the first center it managed was Tall Trees, a juvenile facility in Shelby County. CoreCivic’s stock prices have nearly doubled since the election of Donald Trump.

“Most of the criminal justice practitioners or researchers will tell you the further a child progresses into the system, the more harm is done and the more likely they are to become recidivists later on,” Powell said.

How Juvenile Court got here

Resistance to reform by the Juvenile Court of Memphis and Shelby County dates back to December 2012 when a DOJ investigation found the court violated children’s constitutional rights in three areas.

1. Protection from harm, which included subjecting children to inappropriate and painful pressure point tactics to force children to comply

2. Due process, including providing children with legal representation and giving their defense attorneys access to discovery.

3. Equal protection, where investigators found that at every stage of the process, the court treats black children more harshly than white children, even when the children have the same record and are charged with the same offenses.

At that time, Juvenile Court Judge Curtis Person saw the DOJ’s findings as an accusation that court employees were intentionally mistreating black children — a misinterpretation that Judge Michael, elected in 2014, inherited, Powell said.

Powell, who like Person and Michael is white, had successfully guided a criminal justice institution through reform: He oversaw court-ordered reform at Shelby County Jail after a federal court found the jail had a “20-year history of abysmal leadership, mismanagement, nepotism,” according to a 2005 federal court document.

In that document, an expert hired by Shelby County noted Powell “has provided leadership and professionalism of the highest caliber, and his quiet interventions to stop personality conflicts or overcome interagency disputes have been invaluable.”

But while a federal judge ordered the jail to shape up via a consent decree, the DOJ’s agreement with Juvenile Court was voluntary and thus wasn’t under a judge’s oversight.

“The court was pushing back the whole time I was involved in this,” Powell said. “Even so, we were making progress.”

Each of the three problem areas has its own independent monitor, who visits at least twice a year to observe court operations. The monitors’ progress reports fill an entire section of Juvenile Court’s website.

The changes in protection from harm are the most dramatic. In this area, the court complied with 33 out of 41 provisions.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the harm protection monitor didn’t warrant a mention in Michael’s September interview on WKNO’s “Behind The Headlines.”

But monitors over the two areas where the court still falls short? The judge blasted them, accusing equal protection monitor Michael Leiber of being motivated by profits and due process monitor Sandra Simpkins of being easily swayed.

Leiber will “tell you he’s paid his house off on the money he’s made working as an independent monitor for the Department of Justice,” Michael said on the show, putting the word “independent” in air quotes.

“Sandra Simpkins, who’s a law professor at Rutgers… [it’s her] first time as a monitor. I will tell you, her reports mimic what’s she’s told by the Department of Justice lawyers. Neither are independent.”

Michael’s defense is no defense, Powell contends

Confronted on the show with proof that black children are still treated more harshly than white children, Michael offered this defense: He doesn’t have any control over who police bring to the court, and almost all of the children police bring in are black.

Two weeks after Michael’s TV appearance, Powell went on the same show.

Powell acknowledged the racial demographics evoked by the judge, but as he told MLK50, “that doesn’t excuse the differences in outcome at later stages that are all controlled by the court.”

When compared with a white child, a black child is less likely to get probation, more likely to be transferred to adult court and more likely to be locked up — even when the severity of the crime and the child’s criminal record are the same.

Part of the problem, Powell said, is the court didn’t use objective tools to decide what to do with a child, “so they were going by their gut.”

Powell said he didn’t see any court employee engaged in blatant racial discrimination, but in the absence of formal processes designed to weed out implicit bias, the situation is ripe for bias.

Children have a right to an attorney, too

In the due process problem area, the court is in substantial compliance with 14 of 21 provisions but hasn’t met the goal of providing all children with independent counsel.

Today public defenders represent 60 percent of children who come to Juvenile Court, but private attorneys, chosen from a list maintained by Juvenile Court, represent the other 40 percent.

That creates a conflict of interest, Powell said.

“Those lawyers are beholden to the judge because that’s how they’re getting paid. That’s how they’re making their living,” he said.

Attorneys who are deemed aggressive in their defense of their young clients risk being cut from the panel or worse.

“There have been a number of defense of attorneys who have told me there’s a pattern of the court in filing board complaints against defense attorneys,” Powell said. “Many will see that as an intimidation attempt.”

Those board complaints aren’t public record, and most of what Juvenile Court does occurs behind a veil, unobservable by the general public or the media.

The opaqueness is ostensibly to protect the privacy of children and their ability to move on without the stigma of a Google-able criminal record. But the privacy also cloaks children who are affected in anonymity.

There are no campaigns featuring wrongly accused children, and the absence of a sympathetic character could make it difficult to mobilize the public around the issue.

“Maybe it is faceless,” Powell conceded, “but it’s not colorless, and that’s the problem.

“It’s a system problem, not an individual case problem and you’ve got the court saying, ‘You can’t come in here and tell me how to handle this one case.’ ”

“Nobody’s telling him that!” Powell said. “They are saying, ‘Look at the system.’”

The way forward

Weeks after the county’s top three elected officials sent their letter to the DOJ, the DOJ received another letter.

More than 20 groups — including the NAACP Memphis chapter, Just City Memphis, Stand for Children, the Official Black Lives Matter Memphis Chapter, the Mid-South Peace & Justice Center and Sister Reach — sent a detailed missive outlining all the areas in which the court has fallen short, asking the DOJ to continue its oversight.

The oversight “should not be terminated because JCMSC has not met its obligations,” the letter read.

Demetria Frank, a law professor at the University of Memphis law school and the executive director of Project MI (Mass Incarceration), was one of the signatories.

“We do know that courts like the Shelby County Juvenile Court tend to be more paternalistic with black kids, and we know that black children are treated more like adults,” Frank said, referring to recent research.

Her question is simple: “If we’re going to replace the DOJ monitoring, what are we going to replace it with?” she asked.

The answer isn’t clear: The Department of Justice did not respond to emails, and Luttrell’s office has directed all questions to Michael, whose office has not replied to several emails over more than four months.

Interestingly, a way out was suggested on WKNO by Michael, who is in year-two of an eight-year term. Those who want him out, he said, could “file a complaint with the board of the judiciary that I’m not doing my job properly and have the board remove me.”

Another option, said Powell: “You could have the county commission take a more hands-on view. They control the budget of juvenile court.”

Frank agrees this option would be “more practical and realistic, but it’s going to take some pressure on the court to look at that particular issue closely.”

A far less likely option: Since Juvenile Court hasn’t met the terms of the voluntary agreement, the DOJ could sue the court.

If Juvenile Court didn’t meet the terms of the legally enforceable consent decree, Michael could be found in contempt of court and in theory, jailed.

However Attorney General Sessions — a Republican like Michael, Oldham and Luttrell — has made it clear his distaste for consent decrees, particularly when used to sanction police departments with patterns of mistreatment and abuse of African-Americans.

“That’s why it’s so important that the DOJ people stay there because that’s the only independent voice you have,” Powell said.

Where do we go from here?

Read. Here’s what it takes to file a complaint against a judge in Tennessee.

Sign the petition started by education advocate Kenya Bradshaw in response to MLK50’s reporting about Juvenile Court.

Learn about decades-long mismanagement and sexual abuse at the Shelby County Jail from this 2005 court case.

Study racial disparities in youth incarceration with The Sentencing Project’s latest report.