Federal judge calls Attorney General’s mandatory sentencing decision ‘bad policy’

He cites “many, many horror stories.”

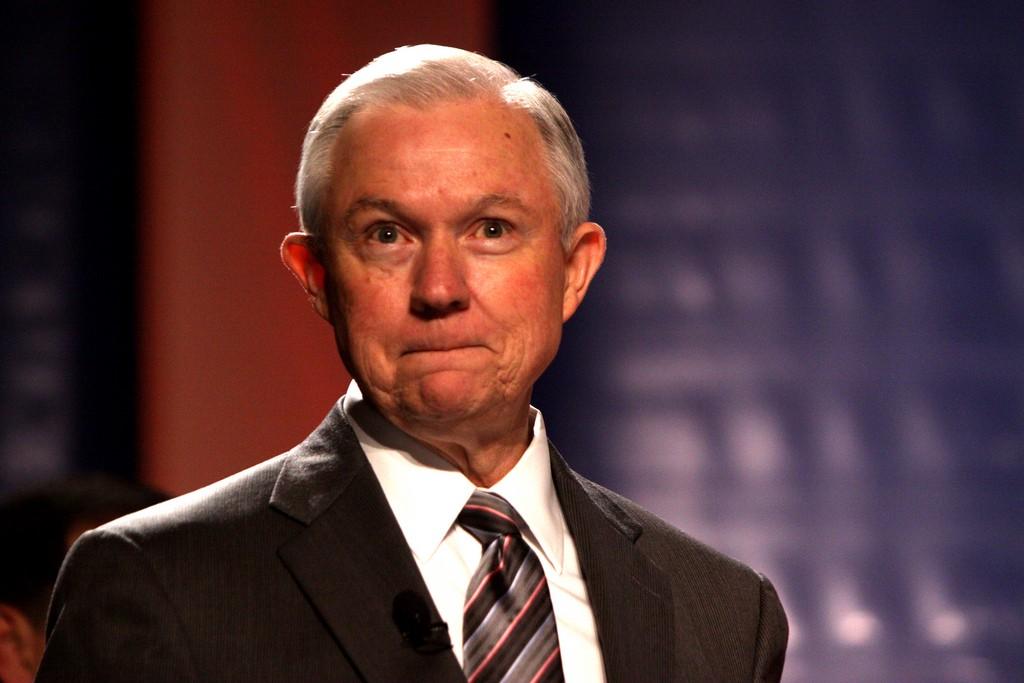

A federal judge in Rhode Island has joined a growing number of judges speaking out against mandatory minimum sentencing across the country. Last week, Chief U.S. District Court Judge William Smith of the District of Rhode Island slammed the harsh federal sentencing mandated by Attorney General Jeff Sessions earlier this year, calling it “bad policy.”

During an interview with local news station WPRI last Thursday, Smith said that he is firmly against this type of sentencing, which imposes immutable prison terms for various crimes and strips away judges’ ability to use discretion during the sentencing process. Mandatory minimums hypothetically level the playing field for convicted offenders, removing the implicit bias underlying sentencing decisions. But in practice, Black and Latino people are far more likely than their white counterparts to receive mandatory minimum sentences. The policy also leads to harsh sentencing that isn’t proportionate to the crime committed.

“There are many, many horror stories about the application of mandatory minimums to defendants who really should not have gone to prison for as long as they did,” said Smith, who was appointed during President George W. Bush’s first term. “I think it’s bad policy to take the discretion away from trial court judges.”

Smith argues that there are many factors that should be taken into consideration when making a sentencing decision, including the nature of the crime and the history of the person who committed it. A blanket policy ignores the context that judges would otherwise account for. “With every defendant, there is a whole story,” he said. “There’s a life that’s been lived — often a complicated life.”

But there’s another glaring problem with mandatory minimum sentencing that Smith left out: it doesn’t work. Researchers and criminal justice advocates have long debunked the idea that it reduces crime. What it has done instead is cause the prison population to skyrocket without increasing public safety.

“Each individual city has its own culture, its own people, history, structure, the relationships between the police and a community,” Greg Newburn, a policy director at Families Against Mandatory Minimums previously told In Justice Today. “We don’t know why crime has gone up in a lot of these cities, and why it’s gone down in others. To say in the abstract that [mandatory minimums are] the better solution is a fool’s errand.”

Rhode Island threw out mandatory minimum sentencing for defendants found guilty of nonviolent drug offenses in 2009. Many other states have passed similar reforms. Nevertheless, people convicted for federal crimes are still haunted by draconian sentencing that Sessions wants heavily enforced.

Smith is not the first to criticize Sessions’ directive. In April, one day after he quit his job as a federal judge in Tennessee, Kevin Sharp condemned mandatory sentencing that leaves judges hopeless. “The drugs-and-guns cases, you say it like that and it sounds like they’re all dangerous,” he told a reporter from the Tennessean. “Most of them are not. They’re just kids who lack any opportunities and any supervision, lack education and have ended up doing what appears to be at the time the path of least resistance to make a living.”

In June, U.S. District Court Judge Mark Bennett of Iowa explained to NPR that this policy also hurts people struggling with drug abuse. “They have a medical problem. It’s called addiction, and they’re going to be faced with five and 10 and 20-year and sometimes life mandatory minimum sentences. I think that’s a travesty,” he said.

But with tough-on-crime Sessions steering the ship, criticism of the policy by federal judges like Smith, Bennett, and Sharp is likely to be ignored.