Even With A Governor’s Pardon, Jesus Aguirre, Jr. Is Still a Gang Member According to Orange County

In March of 2010, Jesus Aguirre, Jr. had just turned 16 and was hanging out with a group of friends in Buena Park, California, when a fight broke out amongst nearly 20 boys. One of the boys fired a shotgun full of birdshot at another teen, who sustained “superficial” injuries, according to the Buena Park Police Department […]

In March of 2010, Jesus Aguirre, Jr. had just turned 16 and was hanging out with a group of friends in Buena Park, California, when a fight broke out amongst nearly 20 boys. One of the boys fired a shotgun full of birdshot at another teen, who sustained “superficial” injuries, according to the Buena Park Police Department report. The victim and witnesses said specifically it was not Jesus who fired the shot, but nonetheless he was arrested, charged as an adult by the Orange County District Attorney’s Office for gang-related criminal assault with a dangerous weapon, tried, and sentenced to life in adult prison.

In other words, Jesus — who hadn’t even fired the gun and was just a kid — was charged and given a life sentence as if he were an adult who had committed a highly aggravated and violent crime.

In February 2014, after various appeals and petitions, an appellate judgereduced Jesus’s sentence to 17 years. This past December, California Governor Jerry Brown commuted his sentence, and Jesus was released on parole. In his letter, Brown remarked on Jesus’s rehabilitation — he has participated in programs ranging from anger management to computer programming and has strong community support — but the governor did not comment on the reasons why Jesus received such a harsh sentence: Orange County prosecutors aggressively prosecuted Jesus as an adult and sought the maximum statutory punishment.

Jesus Aguirre’s case represents the worst of the California criminal justice system: aggressive prosecution of children, based on laws that are biased against kids of color. Abraham Medina, the Executive Director of Resilience O.C., a community group that works with young people of color, told me that Jesus’s commutation “clearly acknowledges that gang enhancements and gang injunctions are often utilized to over-prosecute and over-punish youth in Orange County and across the state in such a manner not conducive to justice for victims or public safety goals.”

Frankie Guzman, Director of the California Juvenile Justice Initiative for the National Center for Youth Law, says that charging kids as adults contradicts the mandate of the juvenile court system that youth should be rehabilitated. “Many kids like Jesus are thrown to the wolves in harmful prison environments without social and family support,” Guzman says. “Against all odds and in spite of a lack of developmental opportunities, Jesus has shown that kids can be rehabilitated.”

At 12, Jesus was sent to an alternative high school and sought out protection from some low-level street gang members from his Orange County neighborhood. Over the course of the next two years, Jesus was arrested some 25 times for minor crimes like graffiti, riding a bike without a helmet, writing on the sidewalk with chalk, and joyriding. (Like many Latino youth in California, Jesus lived in a heavily policed neighborhood where cops target groups of brown teenagers as likely gang members.)

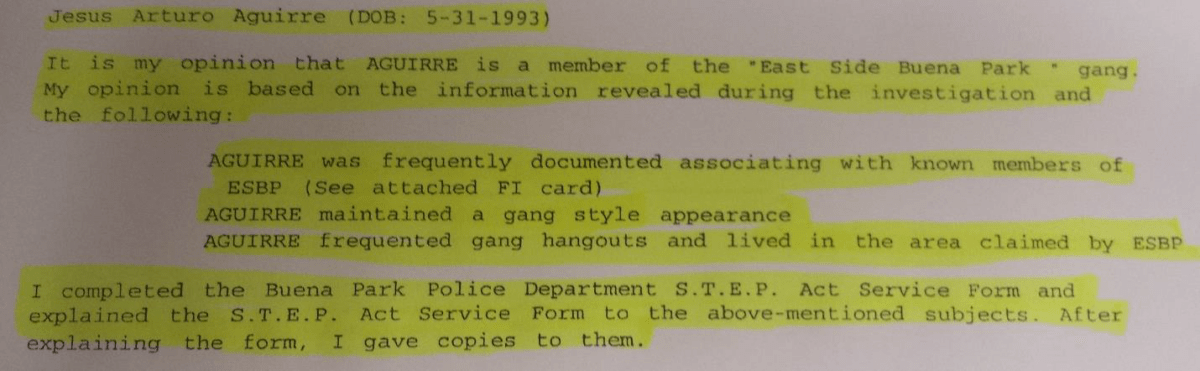

Over half of Jesus’s arrests resulted in a STEP (Street Terrorism Enforcement and Prevention Act) notice, which is like a ticket issued by a police officer for what is perceived to be gang-related activity. Usually, a signature on the document means that the recipient is admitting to being a gang member. STEP tickets were authorized under California’s 1988 STEP Act, which made all alleged gang activity — even minor crimes like graffiti — eligible for enhanced sentences in California; prosecutors use the tickets as evidence that defendants have records of being stopped by the police for alleged gang-related activity. Purportedly, kids (and adults) issued STEP tickets are told about the consequences and asked to sign an acknowledgement, but, advocates say, the reality is that most kids have no idea what the document represents and have little recourse.

STEP notices also placed Aguirre at risk for being placed in CalGANG, the California gang member database, and, by the time Jesus was arrested for the alleged shooting incident in 2010, he had already been profiled by law enforcement as a gang member because of his history of STEP notices and his race. A police report noted Aguirre’s “gang-style appearance” and that he “frequented gang hangouts,” for example, along with his various citations for specific types of graffiti.

Then Jesus was prosecuted as an adult through a process known as “direct file,” which allowed the Orange County prosecutor to move felony cases where the defendant is 14 to 17-years old from juvenile to adult court. Guzman, of the National Center for Youth Law, says that Jesus’s placement in adult court fell entirely within the prosecutor’s discretion. This past November, Californians voted to eliminate the direct file process, requiring a neutral judge to make the ultimate determination, but the vote was too late to help Jesus.

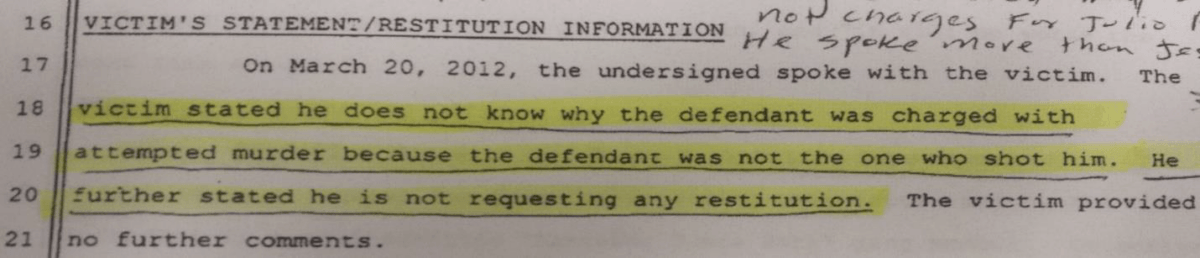

Particularly concerning in Jesus’s prosecution was the use of an undercover informant within the Orange County juvenile facility. As has become clear throughout the still-unfolding Orange County jailhouse informant scandal, Orange County police and prosecutors intentionally and repeatedly used a “snitch” network to obtain incriminating evidence against defendants, especially in gang cases. Prosecutors used this tactic against Jesus, who was detained in juvie on a parole violation while gang unit officers sought more incriminating evidence. Deputies at the juvenile detention center placed Jesus in a cell with a friend, who went by the moniker “Lil Stinky.” The two were recorded for four hours, and, while the full recording has not been released, a gang officer’s summary indicates that both boys discussed various alleged crimes they had committed, as well as the fact that both were at the park the day of the shooting, but hadn’t shot the weapon. (I reviewed the officer’s summary and notes about the recording.)

The DA somehow interpreted Jesus’s statements to amount to a “confession” and filed attempted murder felony charges against Jesus.

While the jailhouse informant scandal has not yet extended to the juvenile system, Jesus’s case suggests that the same aggressive tactics — informants, gang enhancements, and excessive sentencing — used by Orange County DA Tony Rackauckas’s office against adults are also used against young people. “The Orange County DA’s office is notorious for abusing discretion,” says Guzman, “and even for condoning illegal activities to win.”

But, even though the OC DA’s alleged informant network led a judge to toss out the death penalty for a mass shooter, the gang-policing machine continues to mark communities of color. Medina, the community advocate, said that when Jesus went to check in for parole, the Buena Park Gang Unit Officers asked him to sign a STEP notice, acknowledging that he was a gang member. He refused.