Prosecutors Blame Discovery Reform Law For Overtime, Tax Hikes, And a Murder

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. When I was working as a public defender, I was once preparing a trial with another attorney in my office. Our client was facing felony charges, and […]

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal.

When I was working as a public defender, I was once preparing a trial with another attorney in my office. Our client was facing felony charges, and had been incarcerated at Rikers Island for months on bail he could not afford. He had a wife and young children, and spoke to them often by phone. The day before we were set to begin the hearings and trial, prosecutors handed us a stack of about half a dozen CDs, recordings of every phone call our client had made from Rikers over the course of his months inside. We would need to review those calls before starting trial, but there were dozens of hours of tape and less than 24 hours before the hearing was to begin. It was impossible. The prosecutor wouldn’t point us to any particularly pertinent part, and the judge refused to give us any extra time.

On another occasion, I was in the middle of a hearing where I was trying to prove that officers had stopped and searched my client illegally. The officer testified, but I had no idea if what he said was consistent with what he had testified to in the grand jury (which is secret). After he finished his direct examination, the prosecutor handed me the transcript of the officer’s grand jury testimony. I told the judge I would need a recess to read it and prepare a cross examination. “I’ll give you five minutes,” the judge said.

Another time, a young client of mine, who insisted, quite plausibly, that he was innocent, was so desperate to get out of Rikers immediately that he took a plea deal instead of waiting for the prosecutor to turn over video surveillance that could have exonerated him. The prosecutor could have turned over the video, but told me she didn’t want to, and so my client pleaded guilty to a crime he said he did not commit.

This was all legal under New York’s antiquated discovery law, which didn’t require prosecutors to give the defense the evidence against their client until the very last minute. This resulted in many people pleading guilty without ever knowing the strength of the case against them. To many it was known as the “blindfold law,” because it forced people to take pleas while blindfolded. Prosecutors would even sometimes bluff, making their cases seem stronger than they were, in order to extract pleas. Defendants, if they pled, would never find out the truth. In its discovery practices, New York lagged behind the vast majority of states. This finally changed last month, when a new law took effect, requiring prosecutors to give defense teams discovery 15 days after a person is arraigned.

Consider for a moment what it’s like to be charged with a crime without the right to see the evidence against you. You’ll have to decide if it is worth waiting months or years –– maybe on Rikers Island –– to reach trial in order to find out how strong the case is against you. Imagine what it’s like to be the defense attorney, trying for months to counsel your client about whether to take a plea deal without knowing the odds of winning, and then, if the client remains committed to trial, scrambling at the last minute to digest reams of discovery and reformulate trial strategy while also selecting a jury and beginning proceedings. It’s called “trial by ambush” for a reason. Compare that to the new obligations imposed on prosecutors in New York: Hand over discovery within 15 days of arraignment.

In the few weeks since the law has taken effect, prosecutors have managed to blame this new requirement for rising taxes, unbearable workloads, missing filing deadlines, and at least one murder. All of these claims have been false.

The first thing prosecutors say when you suggest that they hand over discovery is that this will endanger witnesses. But somehow, Texas, which has had a far more progressive discovery regime than New York for years, faces no scourge of witness intimidation. And Rebecca Brown, the director of policy for the Innocence Project, told CBS that when it comes to the new law, this is not a legitimate complaint: “There are a ton of protections written into the discovery law that just passed, and in fact, the law that preceded it was a little narrower when it came to victim and witness protections.”

Recently, a few days after a confidential witness in a case against the MS-13 gang was murdered on Long Island, the local police commissioner blamed the new discovery law. Patrick Ryder of Nassau County said that because of the new law, the witness’s information had been shared “too early” with defense teams and suggested that the release of information led to the murder. “We’re asking Albany to go back, rethink it, come back then with changes to that law,” Commissioner Ryder said. “But it needs to happen quickly, before we have another victim, as in this case.”

Reporters quoted him, amplifying his message, many without checking its veracity. But, as the New York Times reported, an examination of court records indicated that the witness information was “never disclosed to the defendants in the case — and that the new criminal justice policies had nothing to do with the murder.” After being “excoriated by criminal justice advocates, Commissioner Ryder walked back his comments,” saying there was “no direct link” between the death “and criminal justice reform.”

Some have also blamed the discovery reforms for rising taxes. The New York State Conference of Mayors recently launched a petition drive calling the new law a “tax hike.” Specifically, they call it, “Governor Cuomo’s criminal discovery reform tax.” The claim is that law enforcement and courts will have to hire more staff and provide overtime in order to turn over the evidence to comply with the law, reports the New York Post. “Freeport raised property taxes by 5.7 percent — the first substantial increase in seven years,” according to the petition, and Freeport Mayor Robert Kennedy blamed Cuomo and state lawmakers for the hike. “We pierced the 2 percent property tax cap solely because of the discovery portion of the new bail law,” Kennedy said. “It’s really unfair.” Cuomo’s budget division spokesperson responded, “the discovery reforms simply ensure defendants are receiving information that has always been provided on the charges against them in a timely fashion, and there’s no reason for this to raise costs for the village unless they were previously not providing basic evidence.” He added that Kennedy “should be presenting his constituents a full accounting of how they arrived at their proposed $2.7 million property tax increase because what he’s claiming doesn’t make sense.”

Prosecutors, meanwhile, are complaining bitterly, saying they are now working 11-hour and 12-hour days. Some are threatening to quit. A public defender who practices in the Bronx and asked for his name to be withheld told me that the “entire Bronx DA’s office took the position that the discovery law didn’t kick in until 1/15 and then gave themselves 30 extra days on every case for ‘voluminous’ discovery.” He added, “They filed a protective order [to limit the amount they need to disclose] in every single case with grand jury minutes,” which amounts to every indicted felony.

Another public defender who practices in New York City who also asked for her name to be withheld told me that prosecutors seem to “feel so persecuted for having to make copies.” One prosecutor, she said, threatened to rescind a plea offer if he had to serve discovery. Even some judges, many of whom are former prosecutors, have decided to weigh in. Recently, in Queens Criminal Court, she saw a prosecutor try to come up with an excuse for failing to respond to a defense motion. The prosecutor told the judge she didn’t know why she didn’t respond. “I just didn’t.” The defense attorney expected the judge to reprimand the prosecutor, but instead, “he asked, with a wink and a nod, if it was because of workload,” apparently referring to the new discovery law. “She caught on to what he was asking and said, ‘Yeah, that’s it. Too much to do with the new laws and all.’” But this made no sense. The prosecutor’s motion was due well before the new laws went into effect.

But, to the governor’s spokesperson’s point, the only way that the new law would impose any new obligations is if prosecutors relied on people taking pleas without ever seeing the evidence against them, obviating the need to hand it over, in a significant number of cases. By claiming that there is any additional obligation, they are essentially admitting that they rely on coercing pleas from people who are blindfolded.

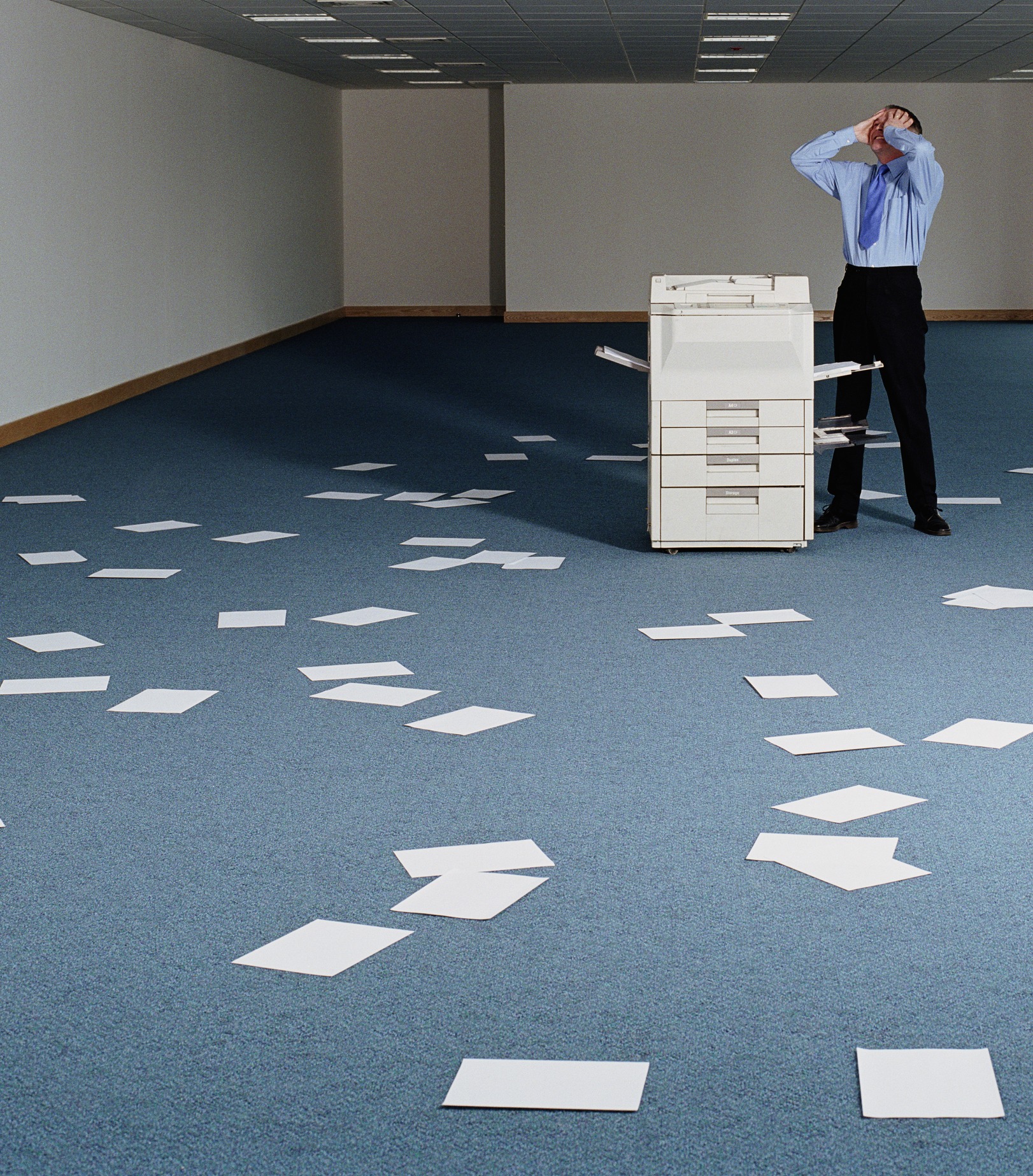

There is one solution that could alleviate prosecutorial caseloads and also honor the new law: Prosecutors can bring fewer cases. If prosecutors only charge and litigate the cases they have the capacity to handle, they won’t have to worry about working long shifts and spending hours over a xerox machine. Prosecutorial discretion is, at least in theory, an integral part of our system. It’s well within their capacity. And despite a drop, low-level prosecutions for such crimes as trespass, driving on a suspended license, and marijuana possession persist (and still target people of color). There is plenty of fat to trim. And if prosecutors simply cannot give up on those low-level marijuana prosecutions, they can simply do what public defenders have been doing for decades: Work late.