Did Prosecutorial Misconduct Result in the Indictment of an African-American Louisiana Couple in a Federal Drug Case?

In the early spring of 2013, Yolanda and Jessie Smith, an African American couple, agreed to accept what they believed were packages of cancer medicine for a 58-year-old white man named Alvin Phillips, whom they knew from a pool hall in Waggaman, Louisiana, a tiny town comprised of about 10,000 residents near New Orleans.

In the early spring of 2013, Yolanda and Jessie Smith, an African American couple, agreed to accept what they believed were packages of cancer medicine for a 58-year-old white man named Alvin Phillips, whom they knew from a pool hall in Waggaman, Louisiana, a tiny town comprised of about 10,000 residents near New Orleans.

The Smiths say they wanted to help Phillips because they believed him to be gravely ill — and they figured they owed him anyway. Around Christmas 2012, he paid an overdue electricity bill for the couple. But in May 2013, soon after agreeing to accept Phillips’s packages, rumors circulated in the pool hall that Phillips had been arrested. The Smiths suspected that perhaps they hadn’t been signing for packages of medicine at all. Phillips had changed his story multiple times. At one point, he told the couple that the packages contained birthday gifts for his son.

Both Yolanda and Jesse live with serious impairments — Jessie is on Social Security for a mental disability and can neither read nor write, and Yolanda has been diagnosed as bipolar, and suffered trauma and abuse as a child. Confused and scared when they heard that Phillips was arrested, they now figured the packages might contain drugs. Still, indebted to Phillips, they felt obliged to accept a package that was already on its way.

On May 30, 2013, Yolanda answered the door at her Dandelion Street home in Waggaman and signed for a package addressed to an “Alan Phillips.” She signed her name as “Patrice Phillips” because she believed that to sign for it, she needed to be a relation to Phillips, and took the package to an outside shed. Meanwhile, high overhead, a police helicopter followed her movements outside of the house. A few minutes later, postal inspectors, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents, and members of the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office stormed into Yolanda’s house and arrested her.

The postman who had delivered the package was actually a postal inspector performing a “controlled delivery” of drugs for a joint task force of local and federal law enforcement agents who had monitored every aspect of the transaction. In the package behind Yolanda’s house, federal agents found methylone, otherwise known as “Molly.” Methylone is a psychoactive drug with properties similar to those of MDMA (better known as ecstasy) and has become a popular street drug in recent years; witnesses later told Yolanda’s attorneys that Phillip was a high-profile Molly dealer in the area.

Customs and Border Protection had intercepted a package from China addressed to Phillips earlier that month, which led to his arrest. Cutting a deal with federal prosecutors, Phillips gave them the names of the low-income black households whose trust he had gained over the previous few months, and to whom he had been arranging deliveries of methylone in order to cover his tracks.

Yolanda was originally charged by state prosecutors with possession with intent to distribute methylone, but in October 2013, the task force returned to their home and served both Yolanda and Jessie with federal drug distribution charges. After her second arrest by federal agents, Yolanda admitted to the arresting officers that she suspected she might be receiving drugs, but had never opened any of the packages to make sure of it. Before that statement, Yolanda, along with the three other black defendants who received packages for Phillips, were indicted by a federal grand jury and each charged with two counts of conspiracy to distribute a controlled substance and one count of possession with intent to distribute. Despite being at the very lowest rung of a drug trafficking network, she was now facing several years in federal prison.

The next spring, days before trial, the three other defendants (along with Phillips) accepted plea deals. But Yolanda was never offered deals by the prosecutors from the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Louisiana. Instead, both Yolanda and Jessie were hit with another grand jury indictment, narrowing the target of prosecution to just the couple, with the same distribution and possession charges lodged against them.

The court severed their two cases, and in early 2015, Yolanda was convicted on all three counts after Phillips and every other defendant who took a plea deal testified against her for the prosecution. Jessie, her husband, was acquitted on all charges when he went to trial over a year later. Yolanda was sentenced to 33 months in federal prison and served almost her entire sentence. Alvin Phillips was sentenced to 51 months, but only served 31.

How did Yolanda end up as the only person convicted at trial in a drug trafficking conspiracy that sparked an investigation involving federal agencies and state law enforcement? The answer is likely an overzealous U.S. Attorney’s office that has long faced accusations of significant prosecutorial misconduct, but has rarely been held accountable by the state and federal agencies meant to monitor this type of overreach.

Following the guilty verdict on January 23, 2015, Yolanda’s lawyer, Sara Johnson, began the appeal process. During the appeal process, Johnson received a document from the court’s sealed record that she had never been given or made aware of during Yolanda’s trial — a complaint from a member of the grand jury to the judge assigned to the case that a high-ranking federal prosecutor had “intimidated and successfully coerced the grand jury into returning an indictment.”

According to the unnamed member of the grand jury, this prosecutor had responded to the grand jury’s skepticism over the case against the Smiths and other defendants “with anger and derision.” Even after the grand jury voted not to hand down an indictment, the prosecutor persisted, telling the jurors he was “insulted” by their decision. Then, the grand juror claimed, the prosecutor “physically approached jurors (including himself) in an intimidating manner, sometimes coming face-to-face.” In his complaint to the judge, the juror claimed the jury only reversed its vote and handed down an indictment because of the threats of the prosecutor.

“The federal grand jury is perhaps the best example of an institution that is designed in a way that’s going to insulate misconduct that occurs,” Jennifer Laurin, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, told The Appeal, noting that grand juries at the state level have taken more steps to loosen the secrecy surrounding their deliberations. “The federal grand jury is closed to all other than jurors and the prosecutors. There’s no judge there. No defense lawyer. Nobody with a committed position outside the government is observing.”

This creates a grand jury process where it’s rare for misconduct allegations to ever see the light of day.

“Absent a situation … like this where you actually have a grand juror coming forward and disclosing something that happened in secret, you’re unlikely to know what was going on in secret in order to argue that you should be able to know what went on in secret,” Laurin explained.

Meanwhile, outside of the grand jury process, prosecutors from the Eastern District have engaged in misconduct that has made national headlines.

Earlier this month, during Senate confirmation hearings for the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals based in New Orleans, Trump-nominee and U.S. District Judge Kurt Englehardt had to answer questions about the Eastern District’s handling of the Danzinger Bridge case, where New Orleans police officers killed two black New Orleans residents and wounded several others in the days following Hurricane Katrina. Englehardt eventually vacated the convictions of four police officers after prosecutorial misconduct came to light. Prosecutors, including the Eastern District’s senior litigation counsel Sal Perricone, had repeatedly commented on news articles about their own cases under pseudonyms like “Henry L. Mencken 1951,” or “eweman,” creating what Englehardt deemed “a prejudicial atmosphere in the community, long before indictments came down, long before a jury could possibly be picked.”

Last week, Louisiana’s Office of Disciplinary Counsel recommended that Perricone receive a one-year suspension from practicing law for his comments, a decision that is exceptionally rare in a state with widespread instances of prosecutorial misconduct.

Laurin hopes the juror’s complaint in Yolanda Smith’s case will help expose other misdeeds. “This is conduct that is out of line,” she says. “If disciplinary entities do not take seriously these allegations when they actually do manage to emerge and approach them with the understanding that this may well be the tip of the iceberg, then you have a real problem on your hands.”

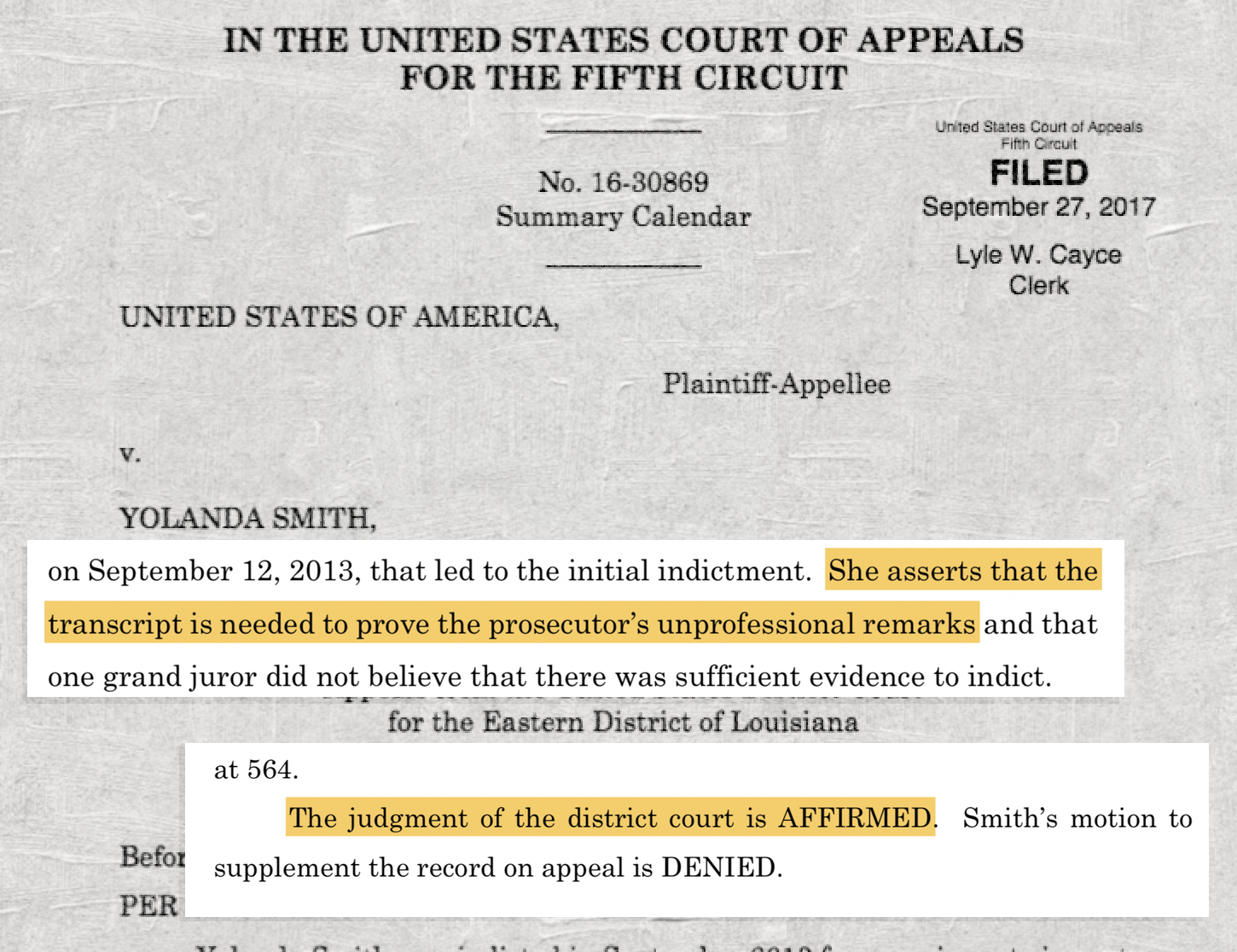

All of Smith’s appeals, which were based in part on prosecutorial misconduct, were unsuccessful. Tragically, while in federal prison, Yolanda’s mother passed away. She is currently living in a halfway house as part of her parole.

Smith’s attorney Sara Johnson filed a complaint about the prosecutor’s conduct with the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Professional Responsibility in June 2017 and followed up in August 2017, but received no response from the agency. Last week, The appeal contacted Kenneth Polite, the former U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District, who oversaw the prosecution of the case, with questions about the conduct of his office. Polite has since declined to comment, but on Tuesday, seemingly out of the blue, the Department of Justice finally informed Johnson that it had begun a “preliminary inquiry” into her complaint.

This story has been updated to specify that it is unclear when exactly Alvin Phillips began cooperating with federal prosecutors.