D.C. Shows Mercy For People Who Committed Crimes As Children, But Prosecutors Are Fighting Back

U.S. attorneys in D.C. have opposed the resentencing of all 14 people who have petitioned for early release under a local law.

During 25 years in prison, David Bailey was written up for one argument and one physical fight, but for the most part, his record was clean. He taught himself to read and write and earned his GED. Despite his life sentence, he enrolled in programs aimed at rehabilitation and he tried to provide his two daughters with emotional and financial support.

He also grew and matured from a reckless 17-year-old who had been locked up in federal prison for second-degree murder into a 43-year-old who knew that his actions had been wrong.

The Supreme Court recognized that such transformations were possible when, based on a growing understanding of children’s brains, it outlawed life without parole for juvenile offenders in 2012. So when the District of Columbia passed a related law in 2016, the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act (IRAA), Bailey said he was cautiously optimistic. The law allowed people who were under 18 when convicted who had served at least 20 years in prison to have their sentences reconsidered.

With the help of his lawyer, James Zeigler, Bailey petitioned the D.C. Superior Court to reduce his sentence and to release him on supervision so he could return to his community in D.C., where in 1994 he had been sentenced to 35 years to life for shooting and killing two people outside a nightclub.

To Zeigler, Bailey was one of the people the D.C. City Council had in mind when it passed the resentencing law. His client had taken anger management courses, reformed his erratic behavior, and generally turned his life around, he said.

But to D.C.’s United States attorneys, the unelected federal prosecutors who represent the people of the nation’s capital, Bailey was still a threat.

“When scrutinized, defendant’s conduct while incarcerated is not that much different than that which resulted in the murder” of the two people he killed, the office of Jessie K. Liu, the U.S. attorney in D.C., wrote in its June 2018 opposition to Bailey’s sentence reduction.

Bailey considers that characterization patently false.

“They had nothing to support that,” he said. “I only got two shots in 25 years. You’re not talking about two months or two weeks or even a year. We’re talking about 25 years.”

It’s not just Bailey whose petition was opposed. In the two years since IRAA took effect, the U.S. attorney’s office has tried to block the resentencing of all 14 people whose motions were heard in court. All but one still had their requests granted by the Superior Court judges and have walked out of prison.

The U.S. attorney’s office has tried to block the resentencing of all 14 people whose motions were heard in court.

In a statement, the U.S. attorney’s office in D.C. told The Appeal that it “does not subscribe to an approach of unilateral opposition.”

“We are mindful that in each of these cases, the defendant has committed a serious crime, such as rape or murder,” said Kadia Koroma, a spokesperson for the office. “Because of this, we thoroughly review each motion and evaluate the defendant’s request for a sentence reduction knowing that this request could affect the victim, the victim’s family, and the community.”

In February, the D.C. government said there were nearly 100 eligible people who could apply for resentencing under IRAA. Zeigler said he expects the U.S. attorney’s office to oppose resentencing in every one.

“Ordinarily, in most systems where you have the executive branch flatly refusing to apply in good faith a law that the legislative branch has enacted, there would be some sort of consequences for this,” he said. “Here, that is not the case. We have no control over our prosecutors’ office.”

At the time of Bailey’s arrest, Washington, D.C., was known as the murder capital of the United States. According to a report by Pew, the city had the highest murder rate of any with a population over 100,000 between 1988 and 1992 and again in 1996, 1998, and 1999.

The criminal justice policies that D.C. and some states adopted at the time came in response to increased drug use and violent crime. Mandatory minimum sentences were introduced and prison populations skyrocketed.

Many of the juvenile offenders whose sentences were reduced under IRAA were convicted during that tough-on-crime period. They had also endured failing public schools and, often, the child welfare system.

“You had a generation of boys in this city who were thrust into this nightmarish scenario,” Zeigler said. “An environment where guns were everywhere—people were getting shot constantly—and for a lot of them, they didn’t have any kind of meaningful social or family support. It’s not a surprise that many of them picked up guns.”

That was one of the reasons that in 2016, the City Council passed the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act. In late 2018, the City Council reduced the number of years required to have been served before petitioning from 20 to 15 and included individuals who had already come up for parole. Members of the council are now pushing to expand the law to include people who were 18 to 25 years old at the time of their offense.

When the Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama in 2012 (and Montgomery v. Louisiana, which made it retroactive), it drew on neuroscience findings that brains are not fully developed until age 25 and that youth offenders are therefore less culpable and have a greater capacity for change.

Since 2012, 28 states and D.C. have changed their laws for juvenile offenders convicted of homicide, according to the Sentencing Project. Over 1,700 juvenile offenders sentenced to life without parole across the country have been resentenced through legislation or resentencing hearings since the decisions, according to Heather Renwick, legal director for the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth.

But prosecutors asked to reconsider sentences often disregard the age of the individual when the crime was committed, instead focusing on the severity of the offense, she said. “We’ve seen a general reluctance among prosecutors to advocate for sentences that allow for meaningful relief for youth who have committed serious crimes,” she said. “We’ve seen a real trend in prosecutors focusing on the facts of the offense to the exclusion of everything else.”

No other prosecutors in the country have unilaterally opposed every juvenile offender’s resentencing.

Prosecutors in other states have also made resentencing difficult. In Michigan, for example, in the four years after the Supreme Court rulings, prosecutors sought the reimposition of life without parole in 60 percent of cases where a juvenile offender was seeking resentencing. That goes against the Supreme Court’s ruling in Miller, which said life without parole should be reserved for juveniles in “rare” or “uncommon” cases.

But in D.C., prosecutors—who aren’t accountable to the legislature in the same way as they are in states because they aren’t elected—have taken an even more aggressive approach. No other prosecutors in the country have unilaterally opposed every juvenile offender’s resentencing, she said.

“D.C. is a unique hybrid jurisdiction where we have a council that enacts criminal justice and then it’s up to the federal U.S. attorneys to enforce and prosecute that law,” Renwick said. “Nowhere else in the country is like D.C. in its mix of state and federal, and I think we’re seeing that play out in these IRAA cases.”

One of the people instrumental in the passage of D.C.’s law was Halim Flowers, who was released in March after a judge granted his motion for resentencing. While incarcerated, Flowers became an advocate for IRAA and its amendments, mentored young offenders, and wrote roughly a dozen books.

But the U.S. attorney’s office still opposed his resentencing. Despite noting that Flowers didn’t have any violent infractions while in custody and had obtained a GED, prosecutors said he didn’t take sufficient responsibility for his actions and therefore should not be resentenced.

Members of the City Council did not understand why the U.S. attorney’s office was opposing every single motion for resentencing—especially Flowers’s. Councilmember Charles Allen wrote a letter to prosecutors on March 11 raising issues with that approach.

“I am concerned that this unilateral opposition does not account for the incredible efforts of many of the petitioners to rehabilitate themselves and restore the harm they have caused,” Allen wrote. “For example, your office is opposing the release of Halim Flowers, who could not present a better case for finding that the interests of justice warrant his release.”

In his letter, Allen said he believes the U.S. attorney’s office is improperly using the facts of the individuals’ crimes to justify their continued incarceration, which is not what the City Council intended when it passed the law.

The Council’s intent was not to require perfection … It was to seek justice.

Charles Allen D.C. City Council

In its statement, the U.S. attorney’s office told The Appeal that by disregarding the original offense, “victims and their families are getting inadequate consideration” under IRAA.

“Our office represents the entire community and we do not agree with the notion that the nature of the offense is irrelevant in deciding whether a reduction in sentencing is warranted,” Koroma, the spokesperson, said.

But the law was passed to give a second chance to people like Flowers. During his February motion hearing, Flowers’s attorneys pointed out that he wasn’t the one to actually fire the gun and that he had spent 14 years incarcerated without a violent infraction.

Standing in his orange jumpsuit before a packed courtroom of supporters, nervous and trembling, Flowers told the judge that he views himself as a changed man.

“I was an impulsive and immature teenager,” he said. “I can honestly stand before this court today to say I have done all I can do to improve myself and the lives of others.”

Listening to his statement and commenting on the government’s opposition, the judge sided with Flowers.

“The intent of IRAA is not to debate the child Halim was,” she said before explaining that she would resentence him in the following weeks. “Halim Flowers is a remarkable adult … and an IRAA success story.”

“It’s hard to imagine there was somebody other than you that this statute was designed for,” she later told him.

Although Flowers is one of the more sympathetic-seeming defendants to seek resentencing under IRAA, not every defendant fits that image. Still, as members of the D.C. City Council said when they passed the law, its intent was to allow second chances for all of the children sentenced to decades-long sentences before they were mature enough to understand their own actions.

“The Council’s intent was not to require perfection; such an ideal is impossible, given the circumstances,” Allen said in his letter to prosecutors. “It was to seek justice.”

In court, prosecutors tried to paint David Bailey as unworthy of resentencing. They called family members of his victims to speak about the pain he has caused them. Prosecutors said in court documents that he “engaged in more violent behavior before his 18th birthday than most hardened offenders are involved in their entire criminal careers.”

What they didn’t say was that both of Bailey’s parents struggled with heroin dependency, according to court documents, and he was born opioid-dependent, which resulted in long-term symptoms. His father was violent toward his mother and as an infant he was passed between homes. He dropped out of school at age 13 and latched onto older children and adults who spent their days on the streets. He began selling marijuana and crack cocaine.

“I didn’t have no structure,” he said. “I didn’t have no guidance.” As a young teen, he went in and out of youth facilities. “You get used to the handcuffs and shackles,” he said. “It prepares you mentally.”

Bailey’s life story was one of the things his attorneys presented during his resentencing hearing in August. But the prosecutors still opposed his release. In its motion, the U.S. attorney’s office called his crime “violent and senseless” and his effort to rehabilitate himself “minimal.”

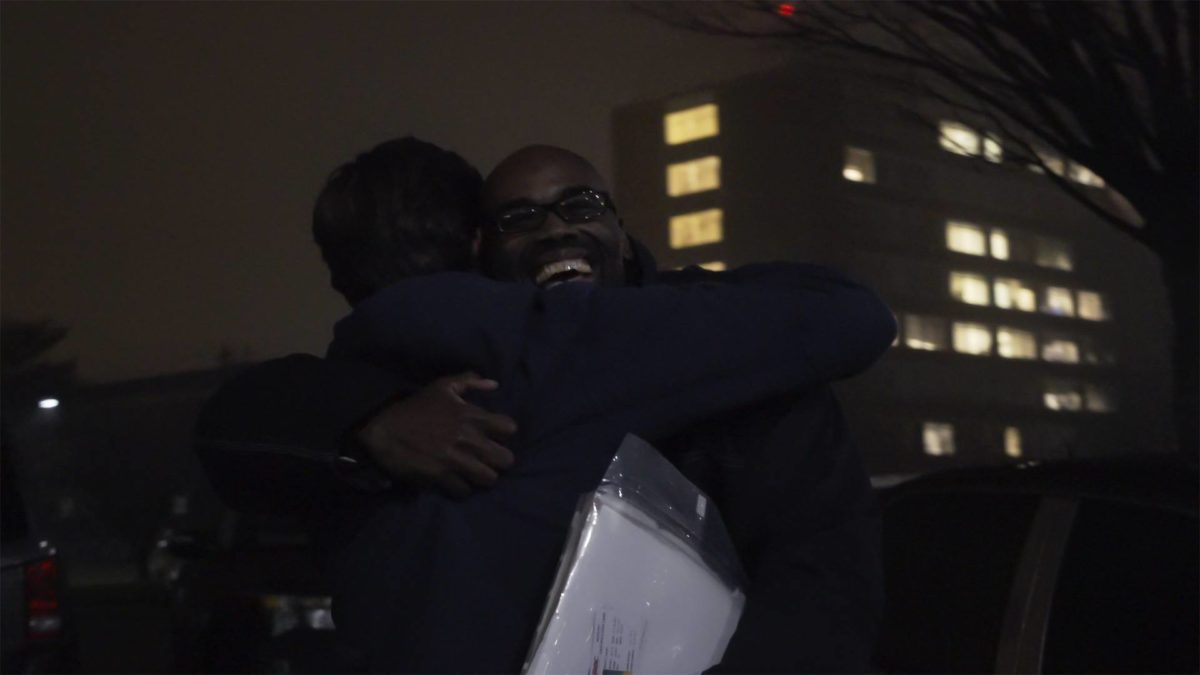

In November 2018, Judge Michael Ryan disagreed with the government, ordering Bailey’s sentence to be modified. On New Year’s Eve, just hours before 2019, Bailey walked out of jail a free man.