New Jail, Same Problems: Why Cleveland is Resisting Plans for a ‘Modern’ Detention Center

Cuyahoga County is the latest community to debate a proposal to build a new jail in response to inhumane conditions at the current facility. Advocates say there’s no such thing as a humane jail.

Support for this article was provided by the Alicia Patterson Foundation.

When Brenden Kiekisz was booked into the Cuyahoga County Jail in Cleveland on Christmas Day 2018, a correctional officer asked him a series of questions, including whether he had ever tried to kill himself. Yes, Kiekisz answered—just two days earlier, though he said he didn’t currently have thoughts of suicide or self-harm. Kiekisz also informed the booking officer that he had depression and bipolar disorder, and was taking several prescription medications. Yet he was assigned to the jail’s general population and was not flagged for mental health monitoring.

Earlier that day, Kiekisz had been arrested on what was supposed to be an unarrestable charge: asking people on the street for money to buy food. He was kept in custody on a year-old warrant for missing a probation meeting, which he’d missed because he was in a mental health treatment facility at the time.

Two days into his jail stay, Kiekisz appeared in court, where he told a judge he hadn’t been receiving his medications. “This is the place that causes the depression,” he said. “I’m losing it in here.” The judge approved his request to be released into mental health treatment. But that night, as he waited alone in his cell to be transferred, Kiekisz attempted suicide and died in a hospital several days later.

“He needed counselors, treatments,” his father, Johnny Kiekisz, told The Appeal. “They got him when he felt depressed, and they didn’t watch over him.”

Kiekisz was one of eight people who died in custody of the Cuyahoga County Jail over a six-month period in 2018, most from suicide or overdose. That year, a scathing investigation by the U.S. Federal Marshals Service revealed that the jail was nearly 700 people over its capacity of 1,765, with 2,420 detainees locked up in “inhumane” conditions. Since 2018, the county has paid over $7 million to settle 13 lawsuits over misconduct in the jail, including assaults by staff. More than a dozen suits remain pending.

The solution to the chronic overcrowding and dangerous conditions, some Cuyahoga County officials say, should involve replacing the aging jail with a brand new facility in a different location. (The two current jail buildings, which are part of a larger Justice Center in downtown Cleveland, opened in 1976 and 1994.) Although plans and estimated costs have shifted repeatedly, one recent projection totaled nearly $2 billion in construction costs and interest payments to fund a new jail capable of holding 1,600 to 2,400 beds.

Until late last year, the plan seemed almost inevitable. The Cuyahoga County Council, the county executive, and members of an advisory steering committee of city, county, and justice system officials all favored green-lighting construction. But in recent months, the push has stalled, thanks in large part to loud, continuous opposition from community advocates.

The debate in Cuyahoga represents a fundamental disagreement, now playing out similarly in communities across the country: Is a new jail the solution to preventing deaths behind bars?

While Cuyahoga’s problems are extreme, the jail conditions seen there are far from unusual. Around the country, an average of at least three people die in jails each day, according to the latest federal data, though that is almost certainly an undercount. Jail detainees tend to be particularly vulnerable; many struggle with substance use, poor health, and poverty. A survey of detainees from 2011 to 2012, the most recent data available, found that two-thirds had a diagnosed mental disorder or had experienced “serious psychological distress” in the 30 days prior. In more recent years, 67 percent of the jail population nationwide is being held pretrial, often because they cannot afford bail. The Cuyahoga County Jail, like many others, is fed by a court system that routinely churns people with mental illness and addiction in and out of jail, according to a Marshall Project analysis published in October.

For decades, county officials and sheriffs have pitched the idea of building “humane,” “state-of-the-art” jails—often with much larger capacities—as a way to curb inhumane conditions and address overcrowding. In a survey of 77 counties that had considered or completed jail expansions as of 2019, officials in around half of those jurisdictions cited overcrowded or aging facilities as a justification. Many reported that they believed the additional space would allow for safer working and living environments, humane programming, and better health care.

“A new jail will be more safe, efficient, and effective both for the prisoners and the corrections personnel,” argued Cuyahoga’s then-County Executive Armond Budish in a press release last year. In 2020, County Councilmember Mike Gallagher cited the U.S. Marshals investigation as a cause for urgency in building a new jail: “We’re under the gun here. The federal government is looking at us. We have all these court cases. We have these deaths that we have to deal with. … We have no choice but to move forward.”

Instead of resorting to a new jail, community advocates like the Cuyahoga County Jail Coalition want to redirect resources to address root causes of jailing, including addiction, poverty, a lack of community mental health resources, over-policing, and unaffordable bail. Although organizers agree Cuyahoga’s current facility has structural problems, including small cells and insufficient sunlight, some argue that the county has not fully explored the option of renovating or rebuilding at the current downtown site, which is conveniently located and accessible by public transportation.

“The most troubling realities of our County Jail have nothing to do with the building itself,” the jail coalition states on its website, arguing they are instead “the result of the very real, human problems perpetuated by administration mismanagement and staff misconduct.”

In a 2021 law journal article, UCLA School of Law Assistant Professor Aaron Littman identified a growing trend of sheriffs and local officials portraying jail modernization as a solution to safety issues. But this sort of proposal tends to miss the mark, he told The Appeal.

“That ‘modern’ jail will be full, and then overcrowded, and then not modern very quickly,” said Littman. “There are perpetual cycles of trying to address problems by building new facilities that don’t work durably. In part because they fill up, and in part because the problem wasn’t really the facility to begin with.”

Josiah Quarles, a member of the jail coalition and the director of organizing and advocacy for the Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless, expressed similar concerns. “Obviously, we don’t want people living in conditions that contribute to deaths, violence, sickness, all of that,” he told The Appeal. “But if we just reimagine this same framework, in a new building, eventually we will get back here again. And it doesn’t take that long, honestly.”

To truly solve these issues, Quarles argued the county must work to decrease the overall population of the jail.

A central point of contention in many jail expansion plans revolves around broader debates about the role carceral facilities should play as treatment providers.

A third-party analysis commissioned by Cuyahoga’s jail steering committee in 2022 said it would be feasible to renovate the county’s existing complex instead of building an entirely new facility. But the study noted that the jail had been built following older standards of “custody and control.” The consultants determined that updating it to accommodate newer standards of “care and custody” would not be practical without the construction of a sizable addition or a major reduction in the jail’s capacity—an option some county officials have resisted due to historic jail populations. The report concluded that building an entirely new jail was “the most reasonable solution.”

“They want to make a jail into a place of care, which it’s just not,” said Quarles. The purpose of a jail shouldn’t be to warehouse people long-term, or to serve as a major care provider for certain segments of the population, he added. “It should be treated as a temporary holding facility.”

Several years ago, officials in Los Angeles County, which incarcerates more people than any other jail system in the world, ignited similar controversy with plans to build a new “mental health” jail. The County Board of Supervisors was ultimately forced to abandon the proposal in 2019, after a coalition of civil rights groups successfully argued that jails are fundamentally the wrong setting to connect people to health care and other services. The alliance rallied around slogans like “Care, Not Cages” and “Can’t Get Well in a Cell,” advocating for the county to invest instead in community-based resources capable of meeting the needs of the people who are most frequently criminalized, as well as the broader population.

Another unresolved factor in the Cuyahoga debate comes down to how big the new or renovated jail would need to be. Advocates argue there is evidence the county can lock up fewer people without harming public safety, which would expand the options to include building a new jail with a smaller capacity—or renovating but not enlarging the current jail.

In March 2020, Cuyahoga, like many U.S. counties, responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by releasing people from jail, dropping the population from about 2,000 to a record low of fewer than 1,000 people.

“The city did not fall apart when we went to 950. And that’s consistent with what happened in every city,” Matthew Ahn, a professor and former public defender who has spoken out against rushing a new jail, told The Appeal. (Ahn is considering a progressive primary run for Cuyahoga County prosecutor.)

Counties that released people at the beginning of the pandemic actually saw a decrease in both crime and overall arrests in the months after, according to a recent study.

But more recently, Cuyahoga’s jail population has crept up from its record low, following similar trends in other jurisdictions. By the end of 2020, the jail had an average daily population of 1,351, before rising to 1,585 in December 2021 and 1,635 in December 2022.

For advocates, dangerous jail conditions are an inevitable product of the U.S.’s overreliance on incarceration to respond to societal problems. In 2018, when the jail’s overcrowding was at its worst, up to 12 people were crowded into cells meant for two. Many slept on mattresses on the floor. Jail officials dealt with extreme overcrowding by “red zoning,” a policy that involved locking down entire units for 27 hours straight, with little to no access to phones and showers. (After the U.S. Marshals report, the jail switched to modified lockdowns called “yellow zoning.”)

Dave Okpara, a member of the Cuyahoga County Jail Coalition, told The Appeal that when he was detained at the jail in 2013, being locked down for long periods in tight spaces with strangers added to the mental stress of incarceration. “You’re uncertain of what your future’s going to be,” he said. “All your responsibilities and stuff are going unattended to in the free world. You’re cut off from your family, you’re cut off from your children.”

Even with a lower jail population today, people in Cuyahoga County Jail continue to report frequent use of solitary confinement, insufficient mental health services, filth and rodent infestations, disgusting food, expensive phone calls, and a lack of drinking water—which allegedly contributed to one man’s kidney failure. Detainees have also accused staff members of continued abuse and mistreatment, sexual assault, and drug smuggling. In February, a Cleveland woman filed a proposed class-action lawsuit alleging that jail officials routinely detain people longer than legally required.

As recently as 2018, a paramilitary team of correctional officers known as the “Men in Black” terrorized and abused detainees, according to the U.S. Marshals report. That year, members of that unit punched and pepper sprayed a woman in the face while she was strapped to a restraint chair. In 2019, a man diagnosed with mental illness was strapped to a chair and punched by two officers, causing a concussion. Another detainee was taken out of view of surveillance cameras and beaten for requesting an extra carton of milk.

In 2020, Lea Daye, a trans woman who was being held in an area of the jail reserved for men, died after overdosing on fentanyl and antidepressants. Among her belongings, Daye’s mother found a letter documenting the jail’s insufficient food and cleaning supplies. The same year, Shone Trawick, a 48-year-old man held on misdemeanor charges, was beaten to death by his cellmate, who had a history of assaults in jail. Several months later, Jose Irizarry, who had mental illness, was released from custody on a cold night without a coat or phone and ended up drowning in Lake Erie. Five people died in the jail in 2022, including two by overdose.

In recent years, correctional officers have been charged and convicted of assaults and smuggling drugs. Former warden Eric Ivey pleaded guilty in 2021 to obstructing justice and falsification after he was caught instructing officers to turn off their body cameras and delete footage following an overdose death. Ken Mills, a former jail director, was convicted in 2021 of falsifying government records and “dereliction of duty.” (He has since appealed and is awaiting a new trial.)

The charges against Mills followed a series of widely reported controversies. In 2018, as the jail was already overflowing with local detainees and additional people held under a contract with the U.S. Marshals, Mills and Budish were actively pursuing lucrative agreements with neighboring counties to pack even more bodies into the facility. Mills was meanwhile gaining notoriety for skimping on food and toilet paper, increasing the cost of detainee phone calls, and attempting to privatize the jail’s medical services.

One of the cost-cutting measures Mills implemented may have contributed to Brenden Kiekisz’s death. Ohio law requires jails to provide a professional medical screening for each detainee upon booking. But after watching surveillance videos of the intake process and deciding too many correctional officers were standing around, Mills sought to trim overtime costs by moving medical screenings to a separate location of the facility. Following the change, more than a quarter of the people booked into jail in December 2018, including Kiekisz, were not screened. If Kiekisz had been able to report his history of mental health diagnoses and suicidal thoughts to a medical professional rather than a standard booking officer, it might have led to him receiving more appropriate treatment.

Amid that string of scandals, Cuyahoga County created the steering committee in 2019 to advise council members on the jail plan. In November 2020, the committee unanimously recommended building a new facility, and in March 2022 it selected the site of a former oil refinery. Budish championed the proposal, apparently determined to finalize the purchase of the land before he retired at the end of last year. He introduced legislation that would fund construction by extending a sales tax increase.

But the plan hit a snag. In April 2022, amid concerns about potential environmental hazards on the proposed site, as well as its distance from public transportation, Cuyahoga County’s public defender, Cullen Sweeney, asked the county to reconsider renovating the existing jail. Months later, both candidates running to replace Budish as county executive—a Democrat and a Republican—spoke out against the contaminated site. Then in October, Sweeney, the county prosecutor, and a judge threatened to sue the County Council if it approved the purchase without further analysis and consideration. In the face of the mounting opposition to the former oil refinery site, the steering committee voted narrowly against recommending the purchase, and the council agreed to pause plans until a new county executive was elected.

The talk of a delay infuriated members of the council who had been pushing for a new jail for years. “Some people with agendas are trying to muddy the waters with social justice issues,” Councilmember Scott Tuma said at a council meeting before the pause. “Social justice issues need to be a component of the jail, but it should be one of many factors that we look at.”

At the beginning of his term in January, the new county executive, Chris Ronayne, said he favors repairing the existing jail and creating alternatives to incarceration.

Asked this month about the Democrat’s current stance on the future of the jail, Ronayne’s office told The Appeal that “we intend to announce our plans soon.” A spokesperson said the administration has been working to “thoroughly analyze” prior reports and assessments, and holding “conversations with numerous leaders and stakeholders locally and across the state about best practices in justice.” The County Council did not respond to requests for comment on its current plans for the jail.

Quarles, of the Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless, said he is hopeful that Ronayne’s plans will align with the goals of advocates who have been calling for jail reduction through increased diversion, meaningful bail reform, and speedier trials.

The Cuyahoga County Jail Coalition has continued to press for more robust investment in services that would help people avoid the justice system altogether, such as housing supports, education, low-cost public transit, and reentry programs. “I would like to see that any proposed expenditures for the jail are matched with expenditures outside of that jail,” said Quarles.

I’m just worried that we’re spending half a billion dollars and we’re not actually addressing the cause of the deaths.

a Cuyahoga County resident, speaking at a public hearing in 2022.

In 2021, the county took a promising step by opening a 50-bed diversion center for people with mental health or addiction issues. Although it was initially intended as a jail alternative, where police could take people suspected of low-level crimes, police have consistently underused the center. The county has since opened the facility to walk-ins outside the legal system, a move advocates have celebrated. Then in 2022, the county opened a new Central Booking center at the downtown Justice Center, intended to streamline the system and reduce time spent in jail.

But the question still remains whether a new jail can provide a path to a more humane legal system.

At public hearings throughout last summer and fall, residents regularly offered testimony urging the council not to rush forward with construction. Many expressed skepticism about whether a new building would lead to less dangerous jail conditions.

“Has there ever been a systematic attempt to explain how those deaths occurred?” asked one community member at an August hearing. “I’m just worried that we’re spending half a billion dollars and we’re not actually addressing the cause of the deaths.”

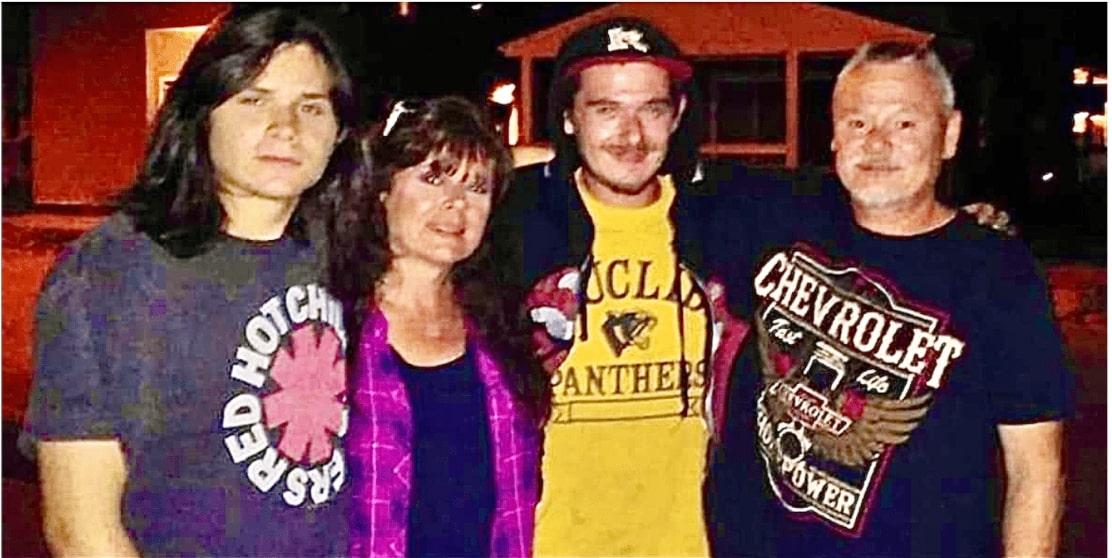

Brenden Kiekisz’s parents said their son’s death in 2018 opened their eyes to the risks inherent to incarceration in Cuyahoga County.

“It’s jail. You go there, you get released, you go home, and that’s supposed to be it,” said his father, Johnny. Although he had seen news stories about deaths and injuries in the jail prior to his son’s arrest, he recalled thinking, “‘Oh, that’s not going to happen to him. We’ll get him out, he’ll get himself out, he’ll sign himself out.’ But it didn’t happen that way.”

“You know, you would think he would be safe there, in the care of the county,” Brenden’s mother, Paula Kiekisz, told The Appeal. “I was wrong.”

Paul Cristallo, an attorney who represented the Kiekisz family, as well as others who suffered abuse in the jail, scoffed at the idea that a new jail would solve the problems that led to Brenden’s death. “They’re blaming the building, they’re blaming the structure,” he said. “Like, ‘look at these horrible, malevolent shower stalls.’”

Last May, Cuyahoga County agreed to pay a $2.1 million settlement to the Kiekisz family. Despite the sizable sum, Cristallo told The Appeal that for years he has seen the county spend millions in taxpayer dollars on lawsuits without making real changes. Earlier in his career, he says he had a crisis of conscience while helping defend the county in a wrongful-death lawsuit brought by the family of Sean Levert, a prominent musician who died at the jail in 2008 after being strapped to a restraint chair and denied his medication.

“For no one—no one—to stand up and just say, ‘Yeah, we got problems; we have completely, utterly, totally, and royally screwed up’?” he said. “What else needs to happen to the county jail?”