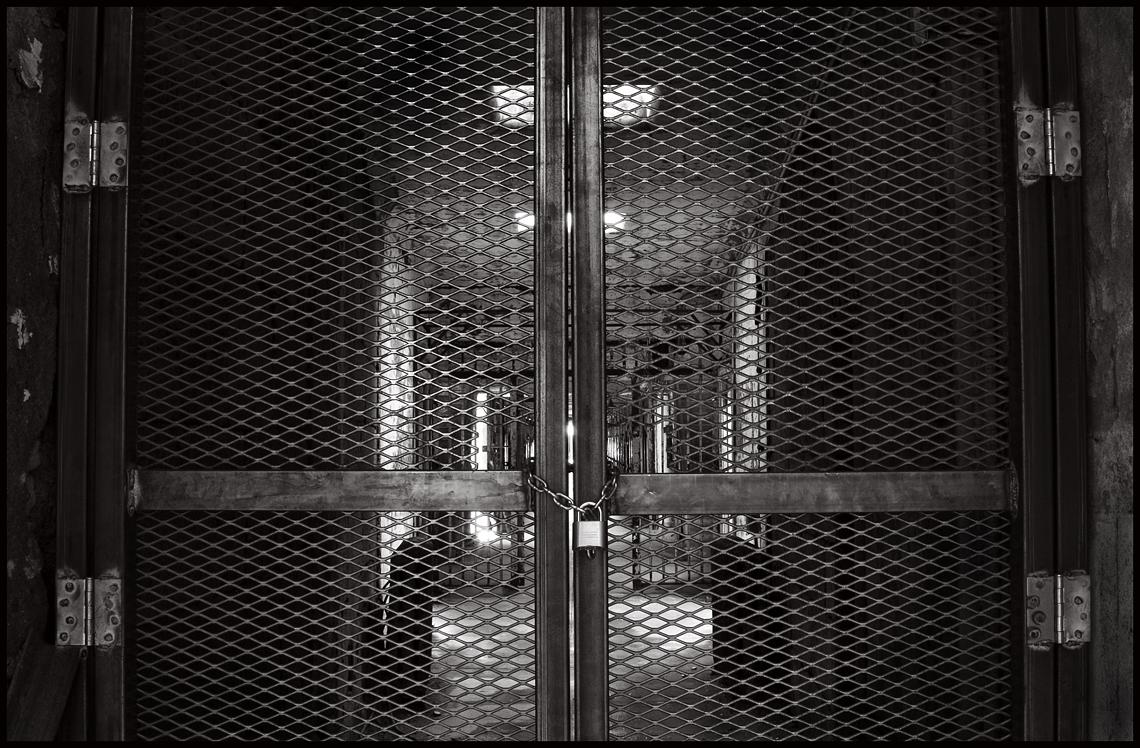

The Pandemic Isn’t Over Inside Prisons—and It Might Never Be

A cycle of hopelessness is taking its toll in prisons across the country, amid continued restrictions on the things that make life more bearable.

“Naw, fuck this, they’re going too far!”

My living unit in the Washington Corrections Center in Shelton, Washington, was on quarantine lockdown, and a disgruntled prisoner was protesting the administration’s decision to give him a new cellmate.

“Every one of us tested negative on this hall, now these guards wanna put someone new in my cell,” he continued. “I don’t know where this dude’s been.”

A crowd was gathering. People were frustrated and looking for a logical explanation for what was happening.

Days before, an active COVID-19 outbreak in three connecting halls had sent us into lockdown. Dozens of prisoners had tested positive, and now guards were moving people from different parts of the facility in a dangerous game of musical chairs.

My unit was panicking.

“This is exactly what happened last year,” another prisoner said, referring to a past outbreak.

“I’m not trying to end up in isolation—shit, it’s worse than solitary,” said a third.

“Why do they keep doing this to us?” asked a fourth.

The resignation set in. There was nothing we could do. It wasn’t as if the guards would listen to our concerns. Even if they did, the decisions were way above their pay grade.

For many on the outside, COVID-19 may no longer be a constant source of anxiety and uncertainty. But in prison, we are still deep in the throes of the pandemic. In January, Washington’s prison system marked its highest-ever number of new COVID cases, with counts far exceeding any previous outbreak.

On the inside, the pandemic has led to severe restrictions on the things that make prison more bearable—visits, positive programming, recreational activities, educational opportunities. And there is no return to normalcy in sight. Although Washington’s incarcerated population was offered the COVID-19 vaccine in the spring of 2021, many of us were not able to get booster shots until mid-February, with officials ironically blaming the near-constant COVID-19 lockdowns. It would be confusing to give booster shots during an outbreak, they’ve said, because it would be unclear whether symptoms were due to the vaccine or to infection.

Prisoners live in constant fear of testing positive for COVID-19 and being hauled off to quarantine, which can be functionally the same as solitary confinement—a recognized form of torture—or involve being crowded in close quarters with nearly a hundred people. Quarantine conditions are so inhumane that some prisoners have begun putting bleach or contact lens solution in their nostrils in hopes of evading a positive test.

In February, I received a dreaded positive result. My head stuffed and foggy, I was told to pack up my personal property and inform my loved ones that I was sick and would soon be moved to a different part of the facility, cut off from regular communication. I didn’t have answers to any of my family’s questions. I couldn’t even tell them when I would be able to call next. I assured them there was nothing to worry about and promised I’d be back in a couple of weeks.

In truth, I was incredibly sick and had no idea what to expect. As I packed up my things, I tried not to let my impending quarantine overwhelm my already cloudy mind. I had written about the torturous conditions of medical isolation in prison. Now I was about to experience them for myself.

Anxiety took over and questions began racing through my mind. Where was I going? How long would I be gone? How sick would I get? Would I receive proper medical treatment? Could I die? Would I be able to talk with my family? What was going to happen to the professional projects I’d spent years developing?

I felt like I might have a breakdown. I had no control over my own health and safety. I was completely at the mercy of prison staff. I tried to take deep breaths, but my COVID-infected lungs wouldn’t cooperate.

I was allowed one box of personal property, which I filled with writing materials, books, clean clothes, and food. I waited for hours with dozens of other COVID-positive prisoners to find out where we were being moved. Finally, we were led to another unit with temporary cells. I bunked with one other person, sleeping with my face a few feet from the toilet.

We asked when we would be allowed out of our cells, but the guards didn’t have answers. They slammed the metal doors shut, and we began our isolation.

We eventually learned that my cellmate and I would be let out together for only 20 minutes each day, to make phone calls, shower, and clean our living space. We always ran out of time, no matter how quickly we moved. I raced through showers and ran to the phone, barely able to dry off. I spent most calls trying to assure my partner that I was OK.

For the next 10 days, I had little to do except lie in our dirty cell, waiting for the experience to end. On the 11th day of quarantine—six days longer than the CDC currently recommends—I was released.

Three days later, when I was at the lowest risk of contracting COVID-19, a guard came to my unit and told us they were offering booster shots.

It’s a mild relief knowing I am as protected from COVID-19 as I can be. But this protection will always be temporary. When the next variant comes, there’s no guarantee that I’ll be spared from getting hauled off to medical isolation again.

This cycle of hopelessness is taking its toll inside prisons across the country. We’ve been forced to go two years without full-contact visits, and our inability to hug and kiss our loved ones has strained many relationships beyond repair. Drug and alcohol treatment and other rehabilitative programs, many of them court-mandated, have been put on pause.

We’ve been told these measures are necessary to protect prisoners from getting COVID-19, but as long as we remain crammed into overcrowded prisons, outbreaks are inevitable. No amount of forced sacrifice can change that. But prison officials can always take more from us, and we have no reason to believe they’re done trying.