Coronavirus In Jails And Prisons

Today’s update focuses on major outbreaks in two state prisons in tiny Buckingham County, Virginia that in June gave it one of the highest per-capita COVID-19 infection rates in the U.S.

Weeks before the first reported cases of COVID-19 in prisons and jails, correctional healthcare experts warned that all the worst aspects of the U.S. criminal justice system — overcrowded, aging facilities lacking sanitary conditions and where medical care is, at best, sparse; too many older prisoners with underlying illnesses; regular flow of staff, guards, healthcare workers in and out of facilities — would leave detention facilities, and their surrounding communities, vulnerable to outbreaks. Despite those early warnings, even jails and prisons that believed they were well-prepared have seen a rapid spread of the virus. On a daily basis over the next several months, The Appeal will be examining the coronavirus crisis unfolding in U.S. prisons and jails, COVID-19’s impact on surrounding communities and how the virus might reshape our lives.

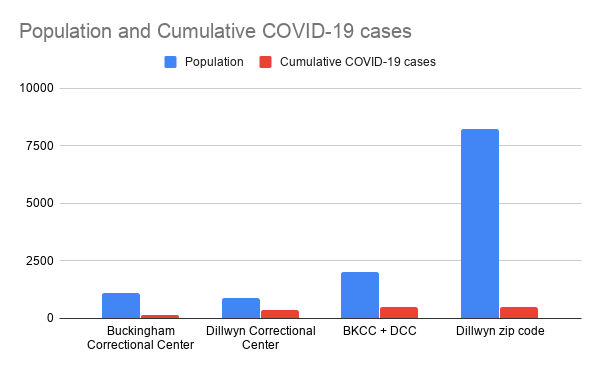

On April 1, WVTF reported that the Virginia Department of Corrections had its first cases of COVID-19, three prisoners and a contractor. A prisoner at Buckingham Correctional Center in central Virginia told the radio station he was afraid guards would bring the virus inside the prison walls. Three and a half months later, Buckingham prisoners account for 165 COVID-19 cases out of the facility’s population of 1,125. Across Prison Road is the Dillwyn Correctional Center which houses 907 people—and 347 COVID-19 cases.

With a population of about 17,000, the two outbreaks gave rural Buckingham County one of the highest per-capita COVID-19 infection rates in the country in June. With 3,064 cases per 100,000 population, it ranked 34th, just behind tiny Galax, Virginia. Galax has the highest cumulative rate in Virginia over the course of the pandemic, according to data from the Virginia Public Access Project, with 4,553 cases per 100,000 population. But in Dillwyn’s zip code it’s higher still: 6,247 cases per 100,000 population. (20 miles south of Dillwyn, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center in Farmville, Virginia has the largest outbreak in the ICE system, where two-thirds of detainees have tested positive, the Daily Beast reports.)

A week after the Virginia Department of Corrections (VADOC) announced its first prisoner cases, 27 incarcerated people represented by Charlottesville attorney Elliott Harding and the ACLU filed suit against the state, including a 48-year-old man housed at Dillwyn with diabetes and high blood pressure. Three weeks later, the VADOC reported 146 cases between prisoners and staff at Dillwyn and another 15 at Buckingham.

Just a few days later, on May 4, there were more than 200 cases at Dillwyn, a leap from seven in just one week. Prisoners described conditions that permitted the virus to spread, including closely packed dormitory-style housing at the medium-security facility—VADOC instructs prisoners to sleep “head to toe” —security officers moving from quarantined buildings to non-quarantined ones, and mixing of quarantined and non-quarantined prisoners in the rec yard.

That same day, several prisoners were transferred out of Dillwyn—for reasons that are still unclear. The ACLU began investigating the possibility that the transfers were meant to defuse a hunger strike, an allegation CBS 19 tracked down to an email from a state official. But one family member told the station that her son, one of the people transferred out of Dillwyn, had said nothing about a hunger strike. Two other family members of incarcerated people told the station they believed it was retaliation for their own advocacy.

Family members told WVTF that the transfers could be traced to a chaotic incident that began when a guard refused to wear a mask, combined with an attempt to cram more quarantined prisoners into an already-crowded bunk room, as well as a lack of hand sanitizer and soap. Incarcerated people reportedly barricaded the doors, under threat of tear gas, until an assistant warden reversed the housing plan. The mother of one prisoner told C-Ville that the plan to add more quarantined people to a quarantined “pod” was the cause—made worse, she said, by the addition coming at the end of a 14-day quarantine period, when they expected to be getting better and on the verge of being released from the pod. VADOC insisted that the transfers were driven by the hunger-strike.

Moving prisoners from Dillwyn has not necessarily spread the disease, but it has spread conflict. On July 10, WVTF reported that people housed in Sussex I, a VADOC facility in the small town of Waverly that received Dillwyn prisoners, allegedly set fires and set off sprinklers in protest. (One Buckingham transferee told his wife that because lockdowns shut down activities such as classes, library visits, therapy, and religious services, stressed-out prisoners were fighting and getting drunk.) The prisoner who told WTVF of the fires and floods Sussex I also said he spends 23 hours a day in his cell due to a COVID-related lockdown; he’s one of 24 prisoners who have filed a complaint with a U.S. district court about the conditions of confinement at Sussex I.

Correction: An earlier version of this article included an incorrect date for a WVTF report on Sussex I. It is July 10, not June 10.