Coronavirus In Jails And Prisons

Pressure mounts on California’s governor to release people from prison; people with months, even days, left on their sentence are dying in Texas prisons; and a new report finds higher rates of COVID-19 in prison than in the U.S. population.

Weeks before the first reported cases of COVID-19 in prisons and jails, correctional healthcare experts warned that all the worst aspects of the U.S. criminal justice system — overcrowded, aging facilities lacking sanitary conditions and where medical care is, at best, sparse; too many older prisoners with underlying illnesses; regular flow of staff, guards, healthcare workers in and out of facilities — would leave detention facilities, and their surrounding communities, vulnerable to outbreaks. Despite those early warnings, even jails and prisons that believed they were well-prepared have seen a rapid spread of the virus. On a daily basis over the next several months, The Appeal will be examining the coronavirus crisis unfolding in U.S. prisons and jails, COVID-19’s impact on surrounding communities and how the virus might reshape our lives. Read Monday’s and Tuesday’s updates.

Today, California prison officials announced that David Reed, a man incarcerated on death row at San Quentin, died while being treated for COVID-19. Reed is the sixth person to die on California death row from complications related to the novel coronavirus.

The announcement of Reed’s death comes after an open letter from more than 200 legal scholars, medical professionals, researchers and justice reform advocates to Gov. Gavin Newsom, urging him to release more people from California prisons to alleviate overcrowding and stop the spread of coronavirus.

The letter credits Newsom for being a champion of progressive issues—as mayor of San Francisco, he issued marriage licenses to same-sex couples, and after being elected governor, he placed a moratorium on the death penalty.

But he’s failed to take substantive action on addressing COVID-19 outbreaks in California prisons. In late March, the state earned praise for releasing 3,400 people who had six months or less left to serve on their sentence. But last week, state Sen. Nancy Skinner noted at a special hearing on the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) response to COVID-19 that the move was unremarkable.

“I just want to make it clear that the numbers … of releases so far are releases that would have been on the natural,” she said. “The fact that since late March we’ve released some 7,000 is not highly unusual at all.”

In the past couple of weeks, Newsom and CDCR have faced growing outrage from attorneys and advocates for incarcerated people alike over botched prisoner transfers that led to outbreaks in at least three prisons that had previously had no cases. At San Quentin, almost half of its prisoner population has tested positive for COVID-19. In tiny Lassen County, public health officials are dealing with a significant outbreak at the California Correctional Center, which trains the state’s incarcerated fire crews.

According to the CDCR patient tracker, there are currently 2,292 people in state prisons with COVID-19 and 31 have died. Among CDCR staff, 1,119 have tested positive and less than half have returned to work.

A quarter of California prisoners are 50 or older, the letter to Newsom notes, and research overwhelmingly shows that the risk of reoffending declines with age. California’s previous efforts to reduce its prison population—2011’s Public Safety Realignment Act and 2014’s Prop. 47—didn’t result in a risk to public safety, the letter says.

“We urge you to follow solid findings in criminology, public policy, criminal justice, and public health, rather than misleading and fear-mongering media reports.”

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has also been criticized for not substantially reducing the state’s prison population. Unlike Newsom, who’s remained mostly silent on the issue, Abbott said in March that “releasing dangerous criminals in the streets is not the solution.”

The Texas Tribune reports that at least 84 state prisoners have died after contracting coronavirus, the second highest death count among state prison systems (Ohio has the highest number of deaths at 86). Among those who’ve died was 73-year-old James Allen Smith, who was sentenced to six months in prison in January to complete a drug and alcohol program.

Smith was housed at Huntsville’s Estelle Unit, where more than 440 prisoners have tested positive for COVID-19, according to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). His family was never told he’d fallen ill. After Smith’s family stopped receiving letters from him, they looked him up on the TDCJ inmate database and learned he was transferred to a prison hospital. In early June, a prison supervisor called one of Smith’s daughters to say he was recovering back at Estelle after a stroke. But that wasn’t the full story. Smith had also tested positive for COVID-19 and died several days later.

The Tribune’s Jolie McCullogh also found other stories of incarcerated people dying from COVID-19 at TDCJ that undercut Abbott’s claim that releasing people early would put “dangerous criminals” on the street.

- Gerald Barragan, 62, was serving five years for possessing two small bags of cocaine

- Joe Channel, also 62, was sentenced to three years for skipping bail on a drug charge that was ultimately dismissed.

- Alfredo De La Vega, 54, died on May 5. He was set to be released May 17 after serving 20 years for aggravated sexual assault.

Texas officials have maintained that only the state’s parole board can decide who gets released early. Prisoners who are mentally ill, disabled, terminally ill, or who require long-term care can qualify for “medically recommended intensive supervision,” but the board rarely approves that type of parole, McCullogh found. In 2019, only 76 prisoners, less than 3 percent of those referred to the board, were released.

Even people housed at the Wallace Pack Unit, a geriatric prison outside of Houston, have failed to secure compassionate release, filing a lawsuit that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court where justices ruled that the plaintiffs needed to take their case back to TDCJ. The judge in the case, McCullogh writes, also believed his hands were tied, yet seemed flummoxed by TDCJ officials’ refusal to release people at risk of dying from COVID-19.

“Would it be difficult for the prison authorities to make an early cut?” U.S. District Judge Keith Ellison asked in a teleconference hearing in April, according to McCullogh. “To say, if people have all these characteristics: they are of compromised health, they are over the age of 65, they have served at least 75 percent of their sentence, and they have a habitat to go to, would it be hard to make that cut?”

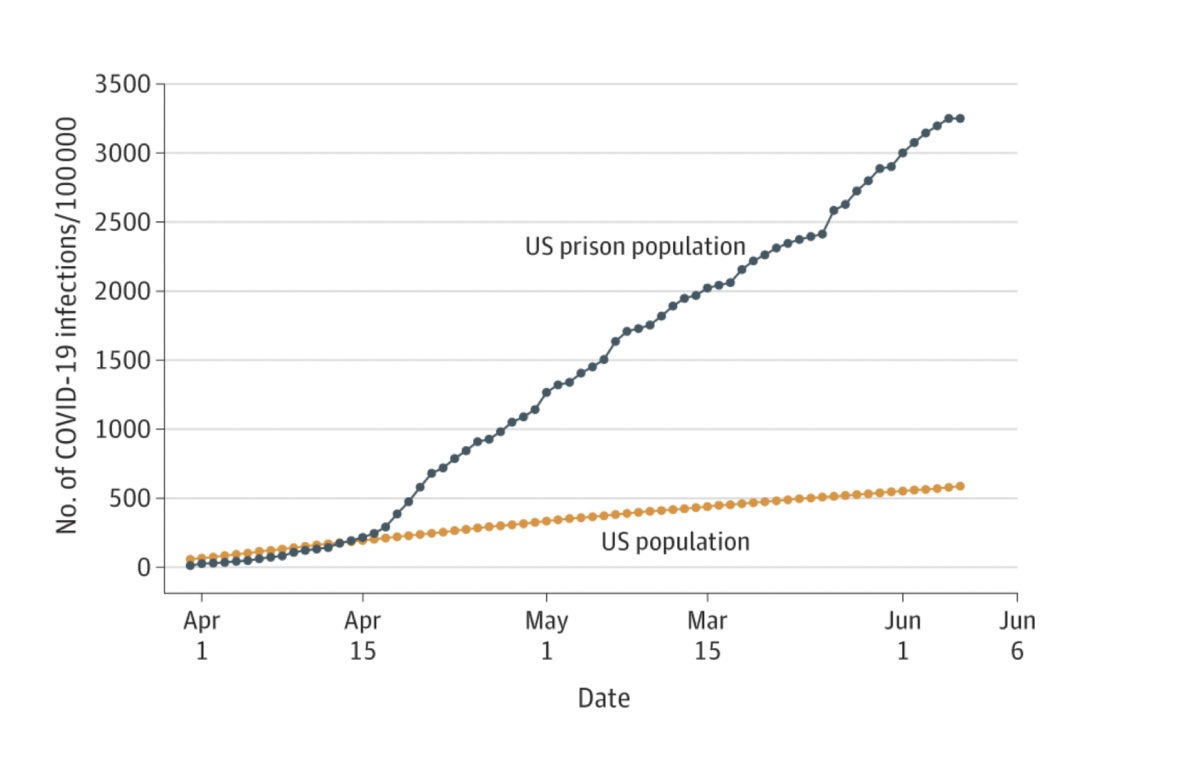

A new report by researchers from UCLA and Johns Hopkins University, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), examines COVID-19 case rates and deaths among federal and state prisoners, finding that cases in custody were 5.5 times higher than in the U.S. population. The COVID-19 death rate in prisons was also much higher, according to the study: 39 deaths per 100 000 prisoners versus the U.S. population rate of 29 deaths per 100,000.

The authors note that the study relied on officially reported data, meaning actual case rates for prisoners are likely higher. The study also found that while the COVID-19 case rate was initially lower in prisons, on April 14 it surpassed the U.S. population, growing at a rate of 8.3 percent per day compared with 3.4 percent per day in the U.S. population.

“Although some facilities did engage in efforts to control outbreaks,” the authors conclude, “the findings suggest that overall, COVID-19 in U.S. prisons is unlikely to be contained without implementation of more effective infection control.”

The report is the first published piece using data from the UCLA Law Covid-19 Behind Bars Data Project.

The Charlotte Observer reports that COVID-19 cases in the North Carolina Correctional Institution for Women skyrocketed over the weekend, leading to the state announcing it would conduct mass testing at the prison. According to the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, 777 women have been tested with 142 testing positive. A woman who spoke to the newspaper said everyone in the prison had been quarantined for the last three months, confined to their dorms and allowed out for only an hour per day. The story says that last month a judge found that prison officials “failed to provide substantial COVID-19 testing” and had transferred prisoners between facilities without enough protection from COVID-19.