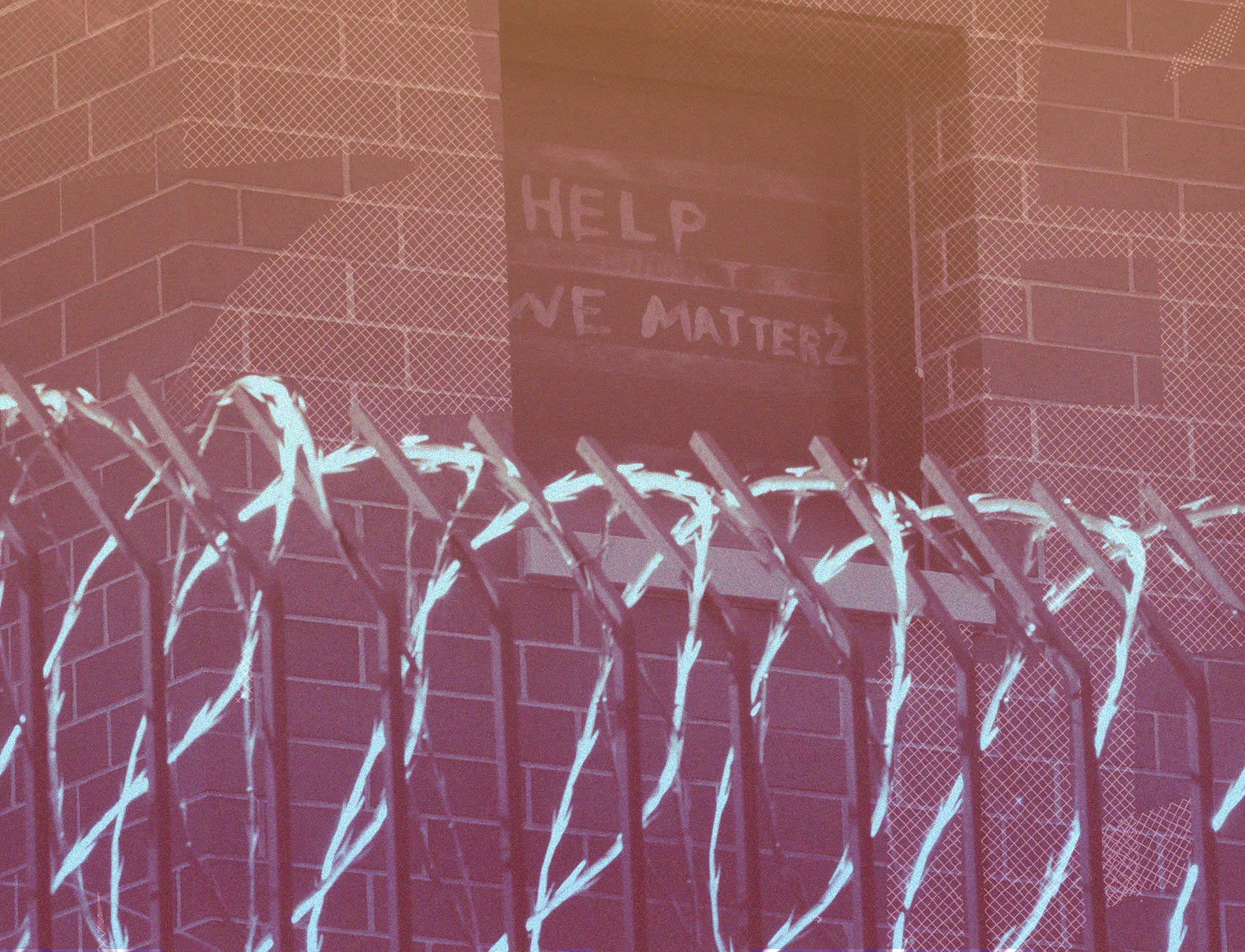

Coronavirus Has Raged Inside American Prisons At A Higher Rate Than Rest Of Nation

All lawmakers have a duty to use every available lever to reduce the number of people in prison, whether by compassionate release or expanded use of furloughs or some other mechanism. Taking these steps will demand immense political courage. But not doing it means consigning people—some just months away from release—to die preventable deaths.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

The disaster unfolding at San Quentin—where over 2000 prisoners have contracted Covid-19 and 13 have died—did not come out of nowhere. For months now, public health researchers and advocates have been sounding the alarm about coronavirus in prisons. Many predicted that overcrowding, poor ventilation and lack of access to masks and soap will make prisons hotspots for infection and sites of disproportionate deaths.

Now we have the data to prove them right. In a study published on July 8 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, our research team analyzed data collected by the UCLA Law Covid-19 Behind Bars Data Project from every state Department of Corrections and the federal Bureau of Prisons. We found that between March 31 and June 6, coronavirus case rates grew by an average of 8.3 percent per day. By comparison, the overall US rate grew by 3.4 percent during that period. As of June 8, there were 5.5 times more cases of coronavirus per capita in prisons than in the US population.

The findings on fatalities are equally chilling. Deaths of prisoners attributable to coronavirus were 34 percent higher than those of the US population, despite the fact that people over age 65—who account for 81 percent of the coronavirus deaths in the US—make up a much smaller share of the prison population. We estimate that, if prisons had the same age and sex distribution as the country, mortality in prisons would be three times higher than the overall US rate.

This understates the true severity of the coronavirus crisis in prisons for one simple reason: testing. Data on testing rates in prisons remains spotty and many prisons appear to be conducting few if any tests. But there are now numerous prisons where mass testing has taken place, and in several cases, alarmingly high numbers of people have tested positive. In April, at Ohio’s Marion Prison (population 2,600) 2,300 tests were administered and 87 percent tested positive. In June, Arkansas’ Cummins Unit Prison, with a population of 1,876, reported 963 positive cases. What Cummins’ total infection rate is anybody’s guess, but that is the point: we should not be guessing.

Current strategies for containing coronavirus in prisons, such as distributing more face masks to staff, placing more prisoners in isolation, or shuffling them to other facilities have proven ineffective, cruel, or—as recently happened at San Quentin—detrimental. Without more drastic measures, the crisis will continue to rage.

Prison officials must take immediate steps to end this crisis. Most urgently, they must conduct universal testing to gauge the current spread of the virus in each facility—and to be transparent about what they find.

Prison administrators must also start pushing elected officials to accelerate releases. Every prison in the country is housing people who do not need to be there, and prison staff know who they are. Ordinarily, this personalized knowledge has no bearing on how long someone remains in custody. But these are no ordinary times, and states need to leverage what custody officers know to inform a nimble coronavirus response. With appropriate guardrails to ensure justice and equity, prison officials should be drawing up lists of every incarcerated person, regardless of crime of conviction, whose release would pose no public safety threat and forwarding those lists to their governors.

In turn, governors should order the immediate release of everyone on those lists, along with everyone whose age and/or comorbidities put them at high risk from the virus while making them unlikely to reoffend. All these individuals should be freed, with or without electronic monitoring, for the duration of the crisis. If it proves politically necessary, they can always be reincarcerated later. For now, the priority should be on reducing prison density to save lives.

All lawmakers have a duty to use every available lever to reduce the number of people in prison, whether by compassionate release or expanded use of furloughs or some other mechanism. Taking these steps will demand immense political courage. But not doing it means consigning people—some just months away from release—to die preventable deaths.

In 1994, in Farmer v. Brennan, the Supreme Court held that, when people in prison are known to face a “substantial risk of serious harm,” they have a constitutional right to protection. At a minimum, until we have a vaccine, we owe it to the people we incarcerate to provide basic safeguards against infection.

Public health officials have been repeating the same mantra for months: socially distance, wear a mask, gather outside. Prisons show just how quickly the coronavirus can spread when these protective measures are impossible. With cases spiking in states across the country and a second wave predicted, the devastating effects of the coronavirus on people in crowded, unhygienic prisons may only just be getting started.

Sharon Dolovich is a professor at UCLA School of Law and director of the UCLA Law Covid-19 Behind Bars Data Project. Brendan Saloner is an associate professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. They, along with Kalind Parish, Julie Ward and Grace DiLaura, are co-authors of “Covid-19 Cases and Deaths in Federal and State Prisons.”