Convicted Of A Deadly Crime As A Teen, He Worked For Decades To Get A Second Chance At Life

Richard Rivera served more than 38 years in prison after killing an off-duty NYPD officer during a botched armed robbery. He was released in July after being denied parole five times.

Every year, 650,000 people return from prison. In The Return, a new series, we will share some of their stories.

Richard Rivera entered the room implausibly hopeful. For the sixth time, he was pleading his case to the New York State Board of Parole.

Rivera, now 55, was convicted of killing an off-duty police officer during a botched robbery at age 16 and sentenced to 30 years to life. He first came up for parole in 2010, but each time, his request for release was heard and rejected. Despite the fact that he was sentenced as a teen and had a documented record of reform in prison, the parole commissioners couldn’t see past his crime. One especially bruising denial came after the panel interviewed him for just 15 minutes.

“I tell people, in no uncertain terms, that the system is stacked against them,” Rivera told The Appeal in his first interview since being released on July 23 from Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch, New York. “You were given a definitive sentence that was imposed upon you with the idea that you will get a meaningful opportunity for release. And then you’re denied over and over again, despite your best efforts.”

A 2016 New York Times analysis of several years worth of parole decisions in New York State found that fewer than 1 in 6 Black or Latinx men was granted release at his first hearing, compared to 1 in 4 white men.

For Rivera, the process felt unfair. “You’re rationalizing all along, because you did something wrong. You did kill somebody,” he explained. “You did something that was horrible and you can never make it up. But we’re nobody’s throwaway creatures. That is the policy that the tough-on-crime philosophy has had, that it distinguished between disposable and non-disposable people. And nobody’s disposable.”

Commissioners Tana Agostini and Tyece Drake, who formed the panel the day of Rivera’s last hearing, came to the same conclusion: After nearly 40 years, they granted his release on parole.

He felt overwhelmed with gratitude, particularly when Drake acknowledged the hard work he’d done to atone and grow while in prison. “Part of going to the board is being validated as a human being,” Rivera said. “As a person who has changed.”

The second-oldest of nine children, Rivera was born in Massachusetts to a single mother who spent large stretches of time institutionalized for a chronic mental illness. Her boyfriend was abusive, he said.

When Rivera was 4 years old, his family, which had moved to Puerto Rico, relocated to New York City, where his childhood was plagued by chaos, neglect, and violence. He stopped attending school at age 8, before he had learned to read or write, and eventually turned to crime to financially support his younger siblings.

Petty larceny and panhandling escalated to riskier behavior and violent crime. As a teen, Rivera said, he was preyed on by men he encountered on the street and developed an addiction to cocaine. The drugs helped him cope with the trauma, he explained, but they also clouded his judgment.

On Jan. 12, 1981, just after midnight, Rivera, then 16, and four other teenagers, each of them masked and high on drugs, entered BVD Bar and Grill in Queens. They intended to rob it.

Armed with both a real gun and a fake gun, Rivera encountered a white man wearing a cowboy hat. The man was NYPD Officer Robert Walsh, who had just finished his shift at 11:30 p.m. and stopped at the Queens bar for a drink on his way home.

Suddenly, the barrel of Walsh’s revolver was pointed at Rivera’s face as the off-duty police officer attempted to thwart the armed robbery. Rivera panicked and shot first.

Walsh, a 36-year-old father of four children and decorated officer with 12 years on the city’s police force, was pronounced dead at a nearby hospital in Brooklyn. He was the third New York City police officer shot in the first two weeks of that year; the other two officers survived.

Two days later, on Jan. 14, 1981, police arrested Rivera and his accomplices. Rivera was charged with felony murder for killing Walsh. A deputy police commissioner described the officer’s encounter with the teen boys as “an execution.”

On March 18, 1982, Rivera was convicted of murder, criminal possession of a weapon, criminal use of a firearm, and robbery. Separately, he was convicted of robbery for a stick-up at a different Queens bar that occurred two weeks prior.

Rivera remembers vividly when the guilty verdict was announced in a crowded courtroom. There were excited murmurs from the Walsh family and their supporters, but there was no one in the courtroom supporting him, not even his own family.

“I could not comprehend the immensity of what unfolding before me. … I had just forfeited my life,” he recalled. So, like the child he was, he focused on the familiar. “I remember wondering if they would be serving breaded fry fish back at the county jail and if I would be able to play a game or two of basketball upon my return.”

Rivera was filled with guilt and shame, but starting in juvenile detention and later prison, he slowly began to transform. He received counseling and treatment for his substance use; he learned to read, got his GED, and attended college classes. Finally, 28 years into his sentence, he was eligible for parole.

But each time Rivera went before the board, the New York City Police Benevolent Association, a union representing tens of thousands of officers, publicly opposed his release. Union members and civilian supporters sent formulaic emails, often with the same subject line, to the Board of Parole.

“Anyone who murders a police officer should be kept in jail for life!” read one email dated Sept. 17, 2012. “If someone is capable of such a crime then they won’t think twice to murder or hurt a civilian. Keep all cop killers behind bars where they belong!”

The Board of Parole interviewed Rivera in 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018, and it denied him release each time.

Members of Rivera’s legal team, which included pro bono counsel from the firm Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe, say hundreds of these emails and letters were sent to the commissioners, encouraging them to keep Rivera in prison. The Board of Parole interviewed Rivera in 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018, and it denied him release each time, arguing that he was still a threat to society.

Meanwhile, the court system was slowly evolving. Research on brain development has proved that adolescents are prone to rash behavior but also likely to outgrow it. The 2012 Supreme Court decision Miller v. Alabama held that it is cruel and unusual punishment to sentence a young person to die in prison. The court banned life imprisonment without parole “for all but the rarest of juvenile offenders,” and required states to provide people like Rivera with a “meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.”

In a strongly worded May 8 ruling, the New York Supreme Court’s Appellate Division said the parole board had failed to do that when it considered Rivera’s request in 2016. In light of his rehabilitation, “the Parole Board’s determination to deny the petitioner release on parole ‘evinced irrationality bordering on impropriety,’” the court wrote.

Tina Luongo, attorney-in-charge of the criminal defense practice at the Legal Aid Society, which represented Rivera, agreed. “Mr. Rivera’s road to recovery and rehabilitation is truly extraordinary,” Luongo said. “Parole is designed to afford people like Mr. Rivera—who accept responsibility for their actions and exhibit remorse—a second chance at life.”

In January 2018, there were 50,271 people in state prisons, according to the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision’s most recent figures. At the time, 8,619 prisoners were serving life sentences and 10,331 prisoners were over the age of 50.

New York’s parole board holds about 12,000 hearings a year and conducts as many as 40 interviews per day, often by video rather than in person. Even after new appointments this year, the parole board remains understaffed; there are still two-person panels interviewing parole candidates, when there should be three, said Michelle Lewin, executive director of the Parole Preparation Project.

In a statement, Thomas Mailey, director of public information for the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, wrote that the Board of Parole was “nearly staffed at capacity” and had its lowest workload last year since 1995. He also noted recent procedural reforms. “In September 2017, the Board of Parole adopted new regulations requiring the Board to consider the individual’s risk and needs assessment, case plan and their age at the time of the offense,” he wrote.

Advocates say more needs to change. In January, a group of New York state senators proposed a measure aimed at encouraging commissioners to base their decisions on who parole candidates are today, rather than on their crimes. The Fair and Timely Parole Act, introduced as Senate Bill S497A, would amend language governing the state’s parole system so that release is presumptive, as long as there is not a “current and unreasonable risk the person will violate the law.” Advocates have estimated this measure would make 12,000 people in New York state prisons eligible for presumptive release, including 2,200 people serving life sentences.

The backward-looking parole system is still very much bent on punishment.

David George Release Aging People in Prison campaign

Groups representing currently and formerly incarcerated individuals, such as the Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP) campaign, have also called on officials to parole prisoners older than 55 who have served at least 15 years of their sentences in a bill known as the Elder Parole Act. Both bills are still in committee.

Between June 2018 and June 2019, the Board of Parole had a release rate of 40 percent. The numbers don’t square with a conservative narrative that everyone eligible for parole is being released, said David George, associate director of RAPP.

“The New York State prison system’s own data indicates that the parole board is not releasing most people who appear before it,” George told The Appeal. “The backward-looking parole system is still very much bent on punishment and thousands of people are still being denied parole today.”

Despite his rejections, Rivera never gave up. At 16, he entered prison illiterate. By the time he left, he was working toward a bachelor’s degree in sociology through Bard College’s prison initiative program.

Gradually, Rivera said, he found his calling in social work. In prison, he was a member of the Inmate Grievance Review Committee, a group that mediates disputes between prisoners and correctional staff. He co-founded the Prisoners AIDS Counseling and Education Program, and helped establish the Hispanic Inmate Needs Task Force as well as a program for older prisoners known as Fifty PLUS.

But Rivera said he never felt such achievements meant he deserved parole more than other men who simply did their time, showed remorse, and changed their ways.

“I think guys could get out of jail with a GED, without a GED, if they have demonstrated change,” Rivera told The Appeal. “I think the most we could hope to do is humanize people.”

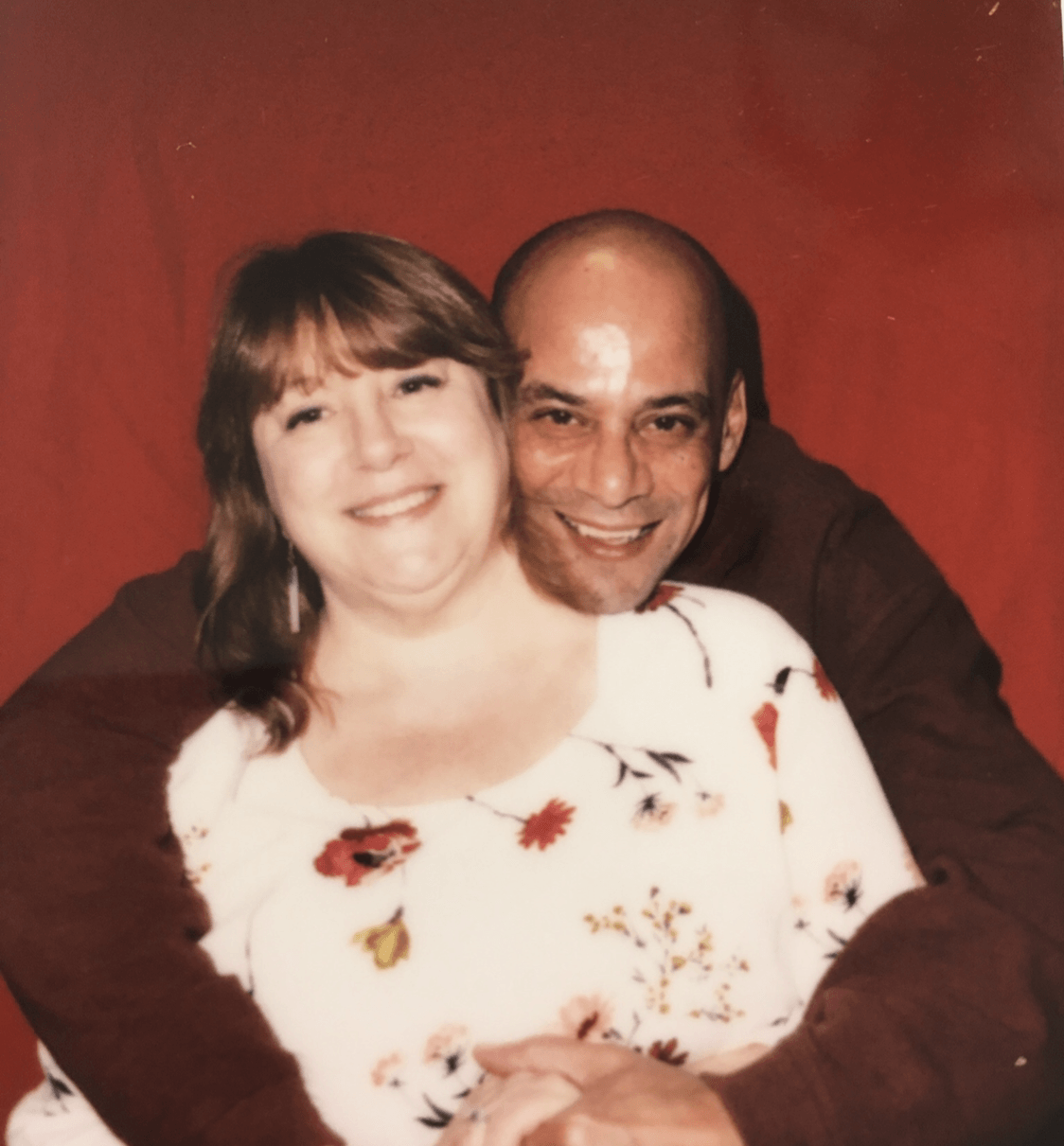

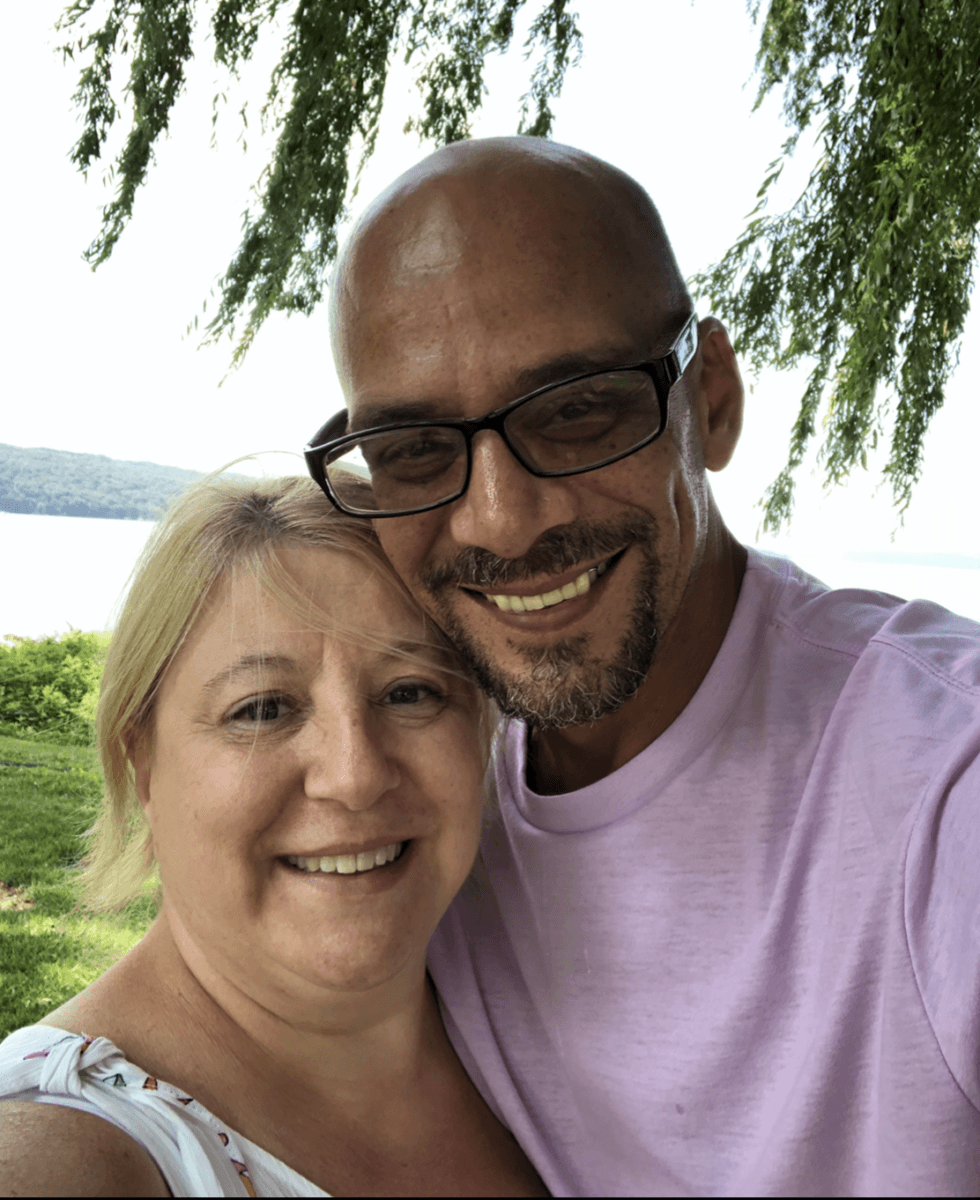

He credits his wife, Kerseinya Rivera, a former social worker at Elmira Correctional Facility, where they met about a decade ago, with helping him come up with a robust re-entry plan, including access to therapy and potential jobs at local nonprofits.

On the day that Rivera spoke to The Appeal by phone, it had been exactly two weeks since he walked out of Eastern Correctional Facility. Things he had only imagined while incarcerated, like using a cellphone freely or walking around Tompkins County Public Library without supervision, were suddenly real. He obtained a driver’s permit and applied for a state ID card. For 39 years, most of Rivera’s meals came from a prison cafeteria, so a recent dinner at Panera Bread restaurant was a special treat, he said.

“I still can’t believe it,” Rivera told The Appeal. “I have a beautiful wife. I live in a beautiful house.”

The incarcerated men still waiting for their chance at freedom are never far from his mind, Rivera said.

“I think the struggle becomes one of hope,” he said. “So, I tell people about my experiences and I explained to them the realities of the process, but I also encouraged them to remain hopeful, to keep fighting.”