Judges Are Exploiting the COVID-19 Pandemic to Advance the Conservative Agenda

A trio of cases in Wisconsin and Texas illustrates how Republican judges are feigning helplessness in the face of a public health crisis while furthering their own ends.

This commentary is part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

Earlier this month, as Wisconsin faced the terrifying prospect of holding a statewide election in the middle of a pandemic, some officials did what they could to avoid a looming public health catastrophe. The Democratic governor, Tony Evers, issued an executive order suspending in-person voting until June and allowing residents to vote by mail in the interim. Separately, a federal district court gave voters who requested absentee ballots a few more days to mail them in, since the state, overwhelmed by COVID-19-induced demand, was unable to send out thousands of ballots by Election Day.

The day before polling places were originally scheduled to open, however—and with the entire state under a mandatory stay-at-home order—two courts stepped in. First, the conservative-controlled Wisconsin Supreme Court struck down Evers’s executive order, restoring the original date for in-person voting. Hours later, the U.S. Supreme Court’s five conservatives threw out the modest extension of the deadline for returning absentee ballots, too. In both cases, the justices claimed to be utterly powerless to prevent hundreds of thousands of people from taking their lives in their hands in order to participate in democracy.

On the day of Wisconsin’s election, another conservative court seized the opportunity to attempt to do something that lawmakers and executives, in ordinary circumstances, could not: functionally ban access to abortion in Texas. The basic logic of these cases is not reconcilable, and it is hard not to notice what the results have in common: a chance to advance conservative ideology and promote Republican politics.

In the Wisconsin cases, both sets of justices went to great rhetorical lengths to explain why they were incapable of ruling in ways that could protect voters from the risk of infection, illness, and death. “This court acknowledges the public health emergency plaguing our state, country, and world,” wrote four of the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s five conservatives for the majority. (The fifth, Daniel Kelly, was up for re-election and recused himself, secure in the knowledge that his absence would not affect the case’s outcome.) But “even if the Governor’s policy judgments … are well-founded,” they continued, the issue “is not whether the policy choice to continue with this election is good or bad,” but instead whether Evers has the authority to act as he did.

Wisconsin law entrusts the governor with broad emergency powers to issue orders that “he or she deems necessary for the security of persons and property.” Evers issued this particular order after determining that postponing voting was “necessary” to prevent people from dying of COVID-19.

To recast this as illegitimate, the court downplayed the relevance of the statutory language, performed some convoluted linguistic gymnastics to dramatically narrow the scope of executive power, and shrugged its shoulders at the disastrous implications of their choice. The conservatives focused their analysis on a different subsection of the emergency powers statute that permits the governor to suspend “administrative” rules. Election dates and procedures are prescribed by statute, though, and because the emergency powers law does not mention a corresponding authority to suspend statutes, they wrote, the “logical inference” is that no such authority exists. As Justice Ann Walsh Bradley pointed out in dissent, the law hardly compels this result, which she excoriated as “tenuous and callous” and “out of step with common sense.”

The U.S. Supreme Court decision put on a similar display of feigned judicial helplessness, but rested on an even sillier set of premises. “Wisconsin has decided to proceed with the elections scheduled for Tuesday, April 7,” said the Court’s five conservatives in an unsigned majority opinion. But, they cautioned, “the wisdom of that decision is not the question before the Court.” Like the Wisconsin Supreme Court, the U.S. Supreme Court instead framed their task as deciding a “narrow, technical question”: whether to uphold the federal court order allowing voters a bit of extra time to return ballots. In four pages, the justices concluded they could not, claiming to be handcuffed by the principle, lifted from a 2006 Supreme Court case, that “lower federal courts should ordinarily not alter the election rules on the eve of an election.”

This is a sensible-sounding rule, but applying it during a pandemic that has already upended so many other spheres of American life is the height of pedantry. By doing so, the conservatives treated that inconvenient “ordinarily” qualifier as if it did not exist. They also asserted that extending the window for returning absentee ballots would “fundamentally alter the nature of the election”; any voters who hadn’t yet received their ballots and felt justifiably afraid to leave the safety of their homes to vote in person, then, were simply out of luck.

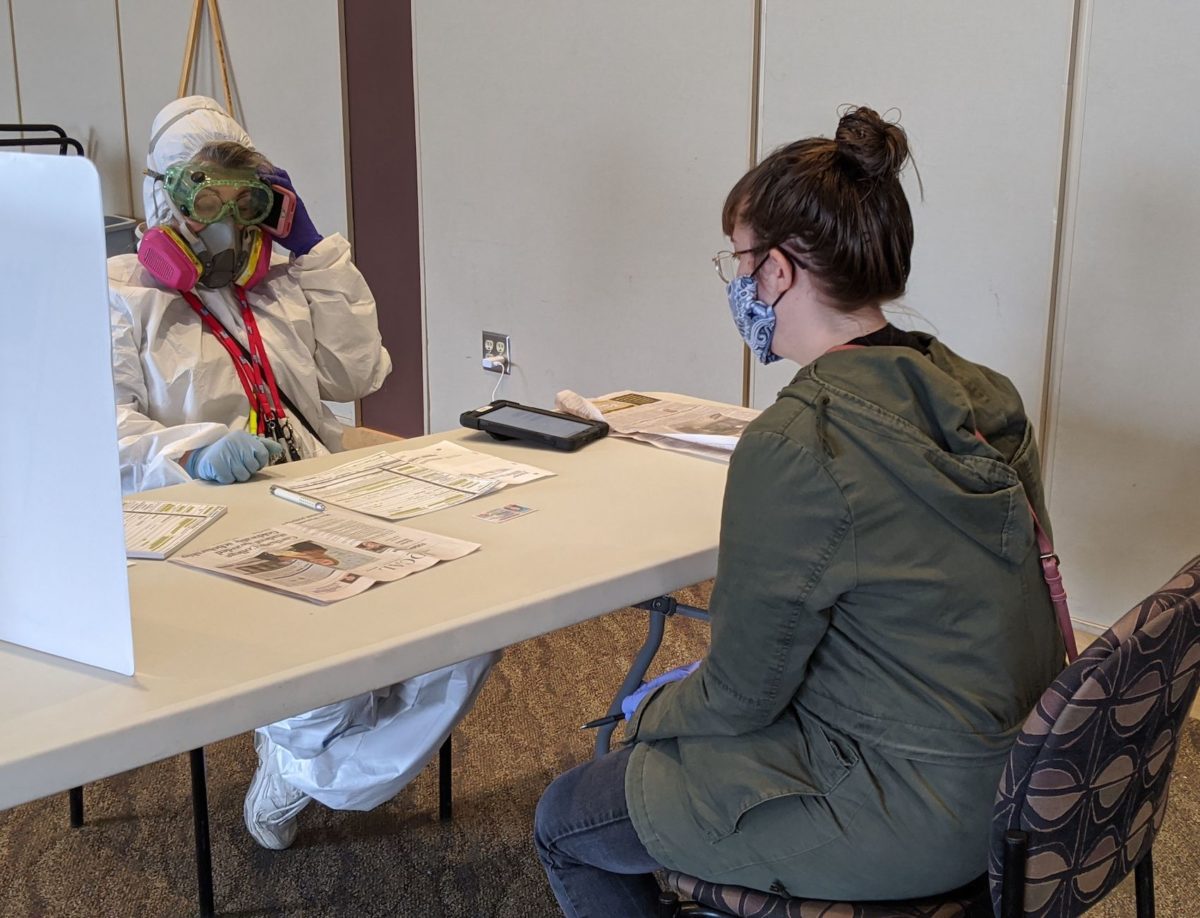

The Court’s blithe assertion here—already dubious on its face—also ignored the fact that holding an election against the backdrop of a deadly disease outbreak was already bound to “fundamentally alter” the contest’s nature. Across the state, clerks said they were short about 7,000 poll workers as the date approached. In Milwaukee, these shortages forced the consolidation of 180 polling places to just five, and lines occasionally stretched for half a mile as nervous voters wearing gloves and bearing Lysol wipes strove to remain six feet apart. In some places, the New York Times reported, poll workers sat behind plexiglass barriers or distributed ballots wearing hazmat suits; nearly everyone waiting in line wore a mask. (Health officials have since said that several people were infected while voting).

In a mewling coda, the conservatives washed their hands of the ramifications of their ruling one last time. “The Court’s decision … should not be viewed as expressing an opinion on the broader question of whether to hold the election, or whether other reforms or modifications in election procedures in light of COVID–19 are appropriate,” they wrote. “That point cannot be stressed enough.” Given that the Court’s conservatives greenlit the election one day before it took place, this apologia paid lip service to the idea of judicial reasonableness while ensuring that none of them actually had to uphold it.

As unconscionable as these decisions are from a public health perspective, they are the predictable results of the conservative justices’ political persuasions. This election stood to have enormous consequences for Wisconsin’s future: In addition to casting ballots for a Democratic presidential candidate, voters flocked to the polls to pick a justice on the hyperpolarized state Supreme Court, fill several seats on the state’s intermediate appellate court, and choose between candidates in thousands of local contests. It was, in other words, not an election conservatives could afford to lose.

Fortunately for Wisconsin Republicans, they have proven to be quite adept at stacking the proverbial deck. Partisan gerrymandering has made a mockery of democracy in the state, where Democratic assembly candidates earned some 200,000 more votes than Republican candidates in 2018 and yet won 27 fewer seats in the chamber. A draconian voter ID law, struck down by a federal judge in 2014 but reinstated on appeal, may have prevented tens of thousands of people from voting in 2016. Here and elsewhere, the task of maintaining the Republican Party’s power has long been contingent on the Republican Party’s ability to hand-pick the people casting the ballots. (In a galling aside, the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s opinion noted that the GOP-controlled legislature could have validly delayed the election “through the ordinary legislative process,” as if the same lawmakers who drew the map establishing quasi-permanent minority rule would ever put their hard-earned hegemony on the line.)

With control of a purple state hanging in the balance, it is no surprise that two results-oriented conservative courts managed to apply rules and decide key cases in ways that made it harder for people to vote, especially in heavily Democratic areas. In Milwaukee County, for example, home to about 16 percent of the state’s total population and two-thirds of its Black residents, MIT political science professor Charles Stewart told The Guardian that turnout was between 35,000 and 50,000 votes below what he expected. Voter turnout in the City of Milwaukee fell by more than 40 percent from 2016. In her dissent, Justice Bradley called the decision “but another example of [the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s] unmitigated support of efforts to disenfranchise voters”; in hers, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote that the majority left “tens of thousands of absentee voters … quite literally without a vote.”

A thousand miles away, Republican leaders of a different state moved to use the COVID-19 emergency to further their partisan agenda. In late March, Texas Governor Greg Abbott issued an executive order postponing “surgeries and procedures” that are not “immediately medically necessary,” ostensibly to preserve personal protective equipment, or PPE, for treatment of COVID-19 patients. The text of Abbott’s order did not mention abortion, but the next day, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton issued a press release treating the directive as if it applied to abortion providers, too—and threatening violators with fines and jail time.

Coming from a pair of staunchly anti-choice politicians, this maneuver looked a lot like an attempt to shoehorn an abortion ban into the state’s pandemic response. Advocates promptly sued, arguing that abortion providers use little to no PPE, and that restricting abortion would do little to prevent the spread of COVID-19. On March 30, a federal district court temporarily blocked the restrictions from taking effect, but a week later, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit intervened, ordering the district court to reverse itself. In the majority opinion, two Republican-appointed judges accused the lower court of “usurp[ing] the state’s authority to craft measures responsive to a public health emergency.”

When a state’s response to an epidemic restricts individual constitutional rights, the Fifth Circuit declared that, under Supreme Court precedent, courts “may not second-guess the wisdom or efficacy” of the state’s response, as long as the measures taken have a “real or substantial relation” to the crisis. “If the choice is between two reasonable responses,” the court went on to say, “the judgment must be left to the governing state authorities.” Here, they said, the lower court “substituted its [opinion] for the Governor’s reasoned judgment”—or, in other words, a lot like what the Wisconsin Supreme Court effectively did to Tony Evers. The fact that the purportedly rote application of this rule in this case happened to advance a key policy goal of the conservative movement went unmentioned by the majority.

As the U.S. Supreme Court did in Wisconsin, the Fifth Circuit reached this conclusion by glossing over conspicuous qualifying language that might lead them to the opposite conclusion. The case the Fifth Circuit cites, a 1905 Supreme Court decision about mandatory vaccination in Massachusetts, warns that although judges should generally defer to the executive in public health emergencies, they may protect people from “arbitrary” and “unreasonable” exercises of emergency powers that have no bearing on public safety. Where unabashedly anti-abortion politicians go out of their way to assert that a neutral policy places sharp limitations on reproductive rights, for example, that might fall within this exception.

In his dissent, Judge James Dennis called out the majority for this bit of selective reading, and accused his colleagues on the notoriously conservative court of reverse-engineering their reasoning to achieve their preferred outcome. “This is a recurring phenomenon in this Circuit in which a result follows not because of the law or facts, but because of the subject matter,” he wrote. “In a time where panic and fear already consume our daily lives, the majority’s opinion inflicts further panic and fear on women in Texas.”

Neither attempt at judicial activism proved as successful as the architects perhaps hoped. Turnout in Wisconsin was higher than many pundits predicted. Kelly, the incumbent state Supreme Court justice, lost his re-election bid to an underdog challenger, liberal Jill Karofsky, narrowing the court’s conservative majority to 4-3. In Texas, a flurry of litigation eventually resulted in a more limited Fifth Circuit decision that left most of the ban in place. A renewed version of Abbott’s order, which will last through May 8, includes exceptions that abortion providers contend will allow them to continue operations. In a press conference last week, Abbott said the issue “will ultimately be decided in the courts.”*

The results of an election, though, do not excuse these courts’ attempts to suppress the vote mid-crisis, or the absurdity of forcing people to vote in person mid-pandemic. And a coalition of abortion providers has already indicated that it will appeal the Fifth Circuit’s ruling, potentially setting up a high-stakes fight in the U.S. Supreme Court, where a conservative majority primed to roll back reproductive rights would have a meaningful opportunity to gut Roe’s promise.

For the same reasons that there isn’t a playbook for officials to respond to a pandemic of this magnitude, there isn’t a well-developed body of law for judges to evaluate these responses, either. As a result, the relevant statutes are broad, and the case law is riddled with caveats to accommodate future scenarios the authors could not foresee. It is a fragile, imperfect framework for crisis management, and its effectiveness depends on courts’ good-faith willingness to resolve ambiguities in flexible ways that protect public health.

In Wisconsin and Texas, conservative judges instead abused their discretion to harm their political opponents. Rather than consider nuances in the law, they pretended no such nuances exist. Their respect for executive power waxed and waned with their respect for the particular executive wielding it. They bent the law to suit their ideological preferences, and then sought to absolve themselves of responsibility for the real-world consequences.

*Update: After this article was published, Texas conceded in a filing in district court that the abortion providers do qualify for one of the exceptions in Abbott’s new executive order, effectively ending this effort to limit reproductive rights in the state.

Jay Willis is a senior contributor at The Appeal.