Georgia Sheriff Stonewalling Official Jail Death Investigation, Medical Examiner Says

The Clayton County Sheriff’s Office is refusing to share information about in-custody deaths with the medical examiner’s office, which is responsible for conducting investigations.

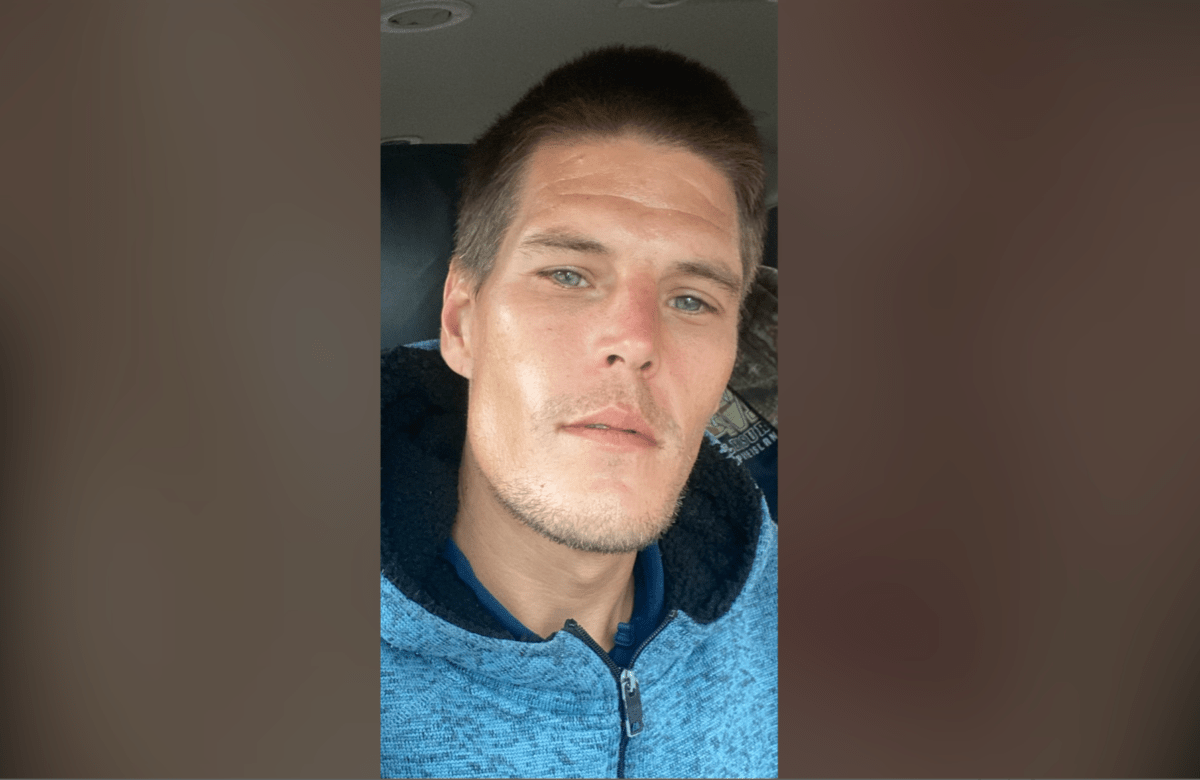

Alan Willison was arrested on a forgery charge in October and sent to Georgia’s scandal-plagued Clayton County Jail, where he’d spend the last three months of his life. On January 26, he died at the age of 32.

Willison’s mother, Tracie Emerson, was on her way to work when she received a call from the hospital telling her that her son had died of cardiac arrest, she said in an interview with The Appeal. Then the jail called and told her he’d died of prostate cancer—which he didn’t have.

“So there was already conflict right there about what happened,” Emerson told The Appeal. “I just don’t understand a lot of this.”

Six weeks later, many questions about Willison’s death remain. Not even the Clayton County Medical Examiner’s Office, which is responsible for investigating all in-custody deaths at the jail, has been able to get answers. Brian Byars, director of the medical examiner’s office, says the sheriff is refusing to provide him with documents related to Willison’s case.

In an interview with The Appeal, Byars said the sheriff’s stonewalling is “dramatically delaying” the investigation into Willison’s death.

“When you don’t get all sides of the story or you don’t get all the information, it’s really hard to come up with a final conclusion of what happened,” he said. “It completely shuts us down from being able to come to a very well-rounded conclusion.”

The sheriff’s office has failed to comply with three subpoenas requesting numerous documents, including incident reports and communications through the inmate messaging system, Byars said. In February, the medical examiner’s office filed a petition with the Superior Court of Clayton County, which accused the sheriff of acting in “bad faith.” Local news outlet WSB-TV was first to report on the filing.

The medical examiner’s office has asked the court to intervene and order the sheriff to comply with the subpoena. The sheriff’s office did not respond to a request for comment by publication.

“I just hope that the public and the citizens of our county feel confident that we’re not going to rest until we get the full story,” said Byars.

But more stonewalling may be yet to come. On Feb. 26, Byars sent a letter to the county police department (an agency separate from the sheriff’s office), metro area hospitals, and the fire department, requesting that they notify the medical examiner’s office immediately if they have or receive knowledge of any in-custody deaths. The “unusual request” was necessary because the Clayton County Sheriff’s Office had communicated that, “they would no longer be contacting us … in regard to in-custody deaths,” wrote Byars. State law requires a “law enforcement officer or other person having knowledge” of in-custody deaths to report them to the coroner or county medical examiner.

The Clayton County Sheriff’s office has been accused of mistreating detainees for years. On Oct. 26—the same day Willison was booked at the jail—former sheriff Vincent Hill was convicted of violating the constitutional rights of detainees when he strapped them into restraint chairs for hours. His sentencing hearing is scheduled for Tuesday. Federal prosecutors have requested a 46-month sentence. In December, his godson, Levon Allen, was sworn in as the interim sheriff. Allen, who Hill has endorsed, is running for a full term against four challengers in a special election. Early voting has already started for the March 21 election.

For the past six weeks, Emerson has been trying to piece together the last few months of her son’s life. After Willison died, she learned that he had been diagnosed with stage four testicular cancer less than a week before his death, she told The Appeal. It is unknown how that may have contributed to his decline. While Willison was at the jail, he told Emerson that “his testicle was hurt and swollen” and that “something’s wrong.”

“Why didn’t somebody reach out to me and tell me that he was this ill? And why didn’t they let him go home to me so I coulda took care of him, instead of dying in a jail,” Emerson said. “Nobody reached out to me for nothing ‘till I got the calls the day he died.”

So far, only the jail’s private medical provider, CorrectHealth, has turned over documents in response to the subpoena, said Byars. Based on the limited information they’ve received, Byars said there are some “troubling facts” around the case. But without more information from the jail, it’s hard to know exactly what may have caused Willison’s death, he added.

“He could have died from testicular cancer,” said Byars. “But under the circumstances, was [medical neglect] a contributing factor? And I don’t know if it is or isn’t.”

Byars said he was a “little shocked” that it appears Willison was only given over-the-counter pain medication like ibuprofen during his incarceration.

“It just didn’t seem like they were very aggressive towards some type of medical treatment, but again, without the jail sharing their information, there’s just not a complete story there,” said Byars.

The county is paying the jail’s medical provider, CorrectHealth, nearly $1 million a month for health care services. The Georgia-based company has faced numerous lawsuits alleging that they have provided inadequate medical care to incarcerated patients.

It also appears Willison was assaulted more than once during his incarceration, said Byars. Violence by both detainees and guards is pervasive at the jail, according to several detainees who spoke with The Appeal. One person said he had been jumped multiple times for refusing to pay his attackers. Another detainee said he was shanked for his t-shirt.

Willison feared for his life while he was locked up, according to his mother.

“He told me through the messaging system, ‘Mom, I can’t say too much on here. There’s too many ears,’” said Emerson. “But he would say, ‘I am scared in here. I need out.’”

Emerson is speaking out so “no other mother has to go through this,” she said, her voice breaking.

“He would do anything for anybody,” she said of her son. “He didn’t deserve what happened to him.”