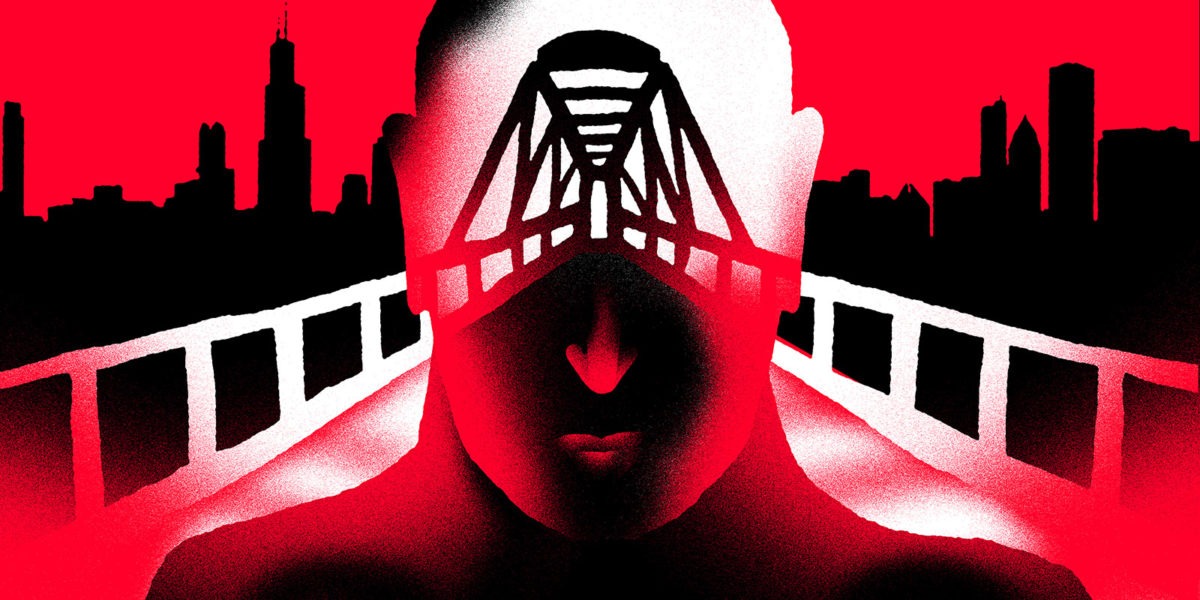

Chicago’s Mayor Turns City’s Infrastructure Into Weapons Against Protesters

When election and racial justice protests rocked the city, Lori Lightfoot used raised bridges and shutdown public transportation as crowd control measures, which harmed the city’s workers.

Minutes before the polls closed on election night in Chicago, massive city sanitation vehicles moved into position outside Trump Tower. Then, the Wabash Avenue bridge—between the president’s namesake building on the north bank of the Chicago River and the Loop central business district on the south—reared up, preventing pedestrians and traffic from crossing.

“Very medieval,” Steven Thrasher, a professor of journalism at Northwestern University, observed on Twitter. Trump Tower, which has been the gathering place for protests since the 2016 election, was suddenly “like a castle protected by the lords pulling up a drawbridge.” Days later bridges were raised again as Chicago residents celebrated Joe Biden’s projected victory in the presidential election.

Bridges raised above the river bisecting downtown have become a common sight in Chicago since late May, when protests over the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis began. It first happened on May 30, as night fell on the protests amid clouds of tear gas, the drone of helicopters, and the shouts of thousands. People who wanted to make their way out of downtown were confronted with dark walls of concrete, steel, and asphalt reaching skyward, severing movement across some of the city’s main thoroughfares. All but two of the bridges separating the Loop from the Magnificent Mile and other busy commercial neighborhoods to the north were raised.

Typically, the city’s river bridges are only raised to allow high-masted boats to pass in and out of Lake Michigan. But that night, for apparently the first time since 1855, the bridges became weapons in Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s aggressive crowd-control arsenal, which also included strategic public transportation shutdowns and highway exit closures to prevent access to downtown. With scarcely a few minutes’ notice—in the form of cell phone emergency alerts—the city announced a 9 p.m. curfew while simultaneously making it nearly impossible for people who’d gathered in the Loop to leave.

The pretext for these actions was public safety. “What started out as a peaceful protest has now devolved into criminal conduct,” Lightfoot said at a May 30 press conference an hour before the curfew. “We want to give people ample opportunity to clear the streets. We’re talking about 35 minutes. I think we’re giving them ample notice.” She said the curfew would help officers “be aggressive in arresting” people engaged in “criminal acts.”

But those who were stranded in the Loop decried Lightfoot’s use of municipal infrastructure, calling it a kettling tactic that makes it easier for police officers to make arrests indiscriminately. Many of the nearly two dozen bridges that span the moat of the Chicago River around the Loop remained raised or closed for days. The city would continue to raise bridges, shut down transit stops and even discontinue bike-sharing services in the vicinity of smaller protests throughout the summer, and in the wake of protests and looting in Chicago’s most prosperous commercial corridors in early August. Lightfoot’s bridge raising and choking of public transit has become so routine that the satirical news outlet The Onion recently declared Lightfoot was unveiling a plan “to replace Chicago’s public transit system with police.”

As Chicago residents and civic organizations documented the effects of these shutdowns, it became clear that they have had serious ramifications on people’s work commutes, healthcare routines, and personal finances. The shutdowns left many feeling that Mayor Lightfoot was more concerned about protecting downtown businesses and some of the city’s wealthiest residents than the police violence that brought people out to the streets. Similar curfews and transit interruptions have become a fact of life in other cities as a wave of demonstrations for racial justice has swept the country.

Robert Alexander, a criminal defense attorney who works in the Loop and lives in South Shore, on the city’s South Side, had been commuting to his office on the bus despite the COVID-19 pandemic. He often works weekends, so he was in the Loop on that Saturday in May. But when he checked the bus schedule he saw that his usual routes weren’t going farther north than 35th Street, nearly four miles away. The trains weren’t running either. “Then I got the notification that the curfew was happening at 9,” Alexander told The Appeal. “This was 8:58. Then I started freaking out.”

He could hear glass breaking on the street; the windows of Walgreens nearby had been smashed and the sprinklers were blasting inside the shop. When he opened ride-sharing apps, no cars were available. He decided he’d try walking the several miles to 35th Street, but when he emerged from his office and onto the street he “saw all these police cars going around and groups of officers walking around, yelling at people. Then I saw groups of white guys with bats walking around and I was like you know what I’m gonna go back to the office. … I’m not gonna lie, I was terrified.”

Alexander, who is Black, thought it would be safer for him to spend the night on the couch in the office even though his building’s call box had been smashed and he worried that someone might break in. He doesn’t remember which mode of transport he took to get home the next day. The road closures and transit interruptions continued into Monday and Tuesday of the following week, but Alexander had to get to his office, where all his clients’ documents are stored, despite the longer and more complicated commutes. “I have incarcerated clients and I was trying to work on motions to try to get them out and away from the pandemic,” he said. “There were police officers, the streets and sanitation trucks, the National Guard were blocking certain exits from the highway.” One day, his ride-share driver got lost making detours around closed streets. “We tried to pull over and ask a police officer for help, and she just screamed at us to keep moving and wouldn’t answer our questions.”

Kyle Lucas, who works at a hotel in the River North neighborhood and lives on the Far North Side, was also stranded the night of May 30. At one point in the evening, Lucas, who is also co-founder of transit advocacy group Better Streets Chicago, stepped outside and witnessed people panicking, crowds of cops, and a squad car in flames. “I remember people just desperately trying to get home,” Lucas told The Appeal. “They were scared.” At every turn, the city’s response to peaceful protests and civil unrest disappointed Lucas. “It’s definitely eroded my trust in the city, in the reliability of the transportation system, it’s eroded my views on the mayor and her commitment to enacting real change,” he said. “I think a lot of people saw the bridges being raised as if to protect the rich and the wealthy and the property downtown in light of people marching and protesting because of massive inequities and injustices in our city, particularly toward Black people. I think it was a very visual reminder for a lot of people of that disparity and I absolutely believe it escalated tensions and made people more angry.”

Over the next several days and throughout the summer as the city continued to limit transit service in response to protests and looting, Lucas, who was able to bike to work, watched some of his co-workers from farther-flung neighborhoods become consumed by the mental and financial strain.

One of them was Robyn Oliver, a security guard who lives in the Roseland neighborhood on the Far South Side, 14 miles away from the hotel near the Ohio and State Street intersection.

“You couldn’t even imagine the hell I had to go through to get to downtown,” Oliver told The Appeal. Normally her commute can take as long as two hours because she works the night shift when bus and “el” train service is more sporadic. But on May 30, as she was on her way to work, the train only made it as far north as 63rd Street. “They stopped the ‘el,’ there was no shuttle buses, no nothing, so I was just stuck there. … I was scared because I didn’t know the neighborhood.” Oliver—who regularly deals with harassment from young people who mistake her for a police officer because of her security guard uniform—said she ended up throwing her uniform jacket in the garbage that night after seeing people ransack a gas station. Ultimately she reached her supervisor who drove out to pick her up. For the next several weeks she was going to work hours earlier than usual, losing out on sleep. “I don’t start till 11 and I start showing up at 5,” she said “I had to show up early just to get there because they lifted the bridges and once darkness hits you’re on your own.” Ride shares weren’t a viable option because it would have cost her nearly $60 one way.

“I would never vote for Lightfoot again and I am gay,” Oliver said. (Lightfoot is Chicago’s first Black female, openly gay mayor.) She added that the usual lack of city services on the Far South Side, such as reliable transit and adequate streetlights were compounded by the city’s responses to the protests. She said Lightfoot’s actions didn’t seem to do much to protect her from the violence that broke out alongside these demonstrations, either. “She did not protect the South Side and us people that worked late nights. I’m going down there to protect their property, but yet I’m fittin’ to get my ass beat for being a security guard on the way.”

Late one evening in early August, Mike Gerardi was thinking about those disparities of race and class as he sat in gridlocked traffic on one of the city’s expressways. He lives in Beverly, on the Far Southwest Side, and at the time worked the night shift as a boiler engineer at the Cook County Jail. His commute along the city’s highways required passing a downtown interchange, which was blocked by huge sanitation vehicles. The city had again blockaded downtown as a rash of looting broke out after police shot a Black man in the Englewood neighborhood. Public transit routes were also interrupted, and the Chicago River bridges were raised once again.

Gerardi was nervous about clocking in for his shift on time. His bosses are strict about lateness and racking up an infraction over something like an unforeseen traffic disruption would perhaps prevent him from taking time off during a real emergency. He didn’t blame the looters as he sat in stalled traffic for more than 45 minutes, though. “By early August I almost felt used to it, this is the thing Chicago does now, block off downtown to keep looters out of the Mag Mile, to keep protesters out of the Loop,” he said. “A bunch of people running around are not the ones who closed off the exit ramp that made my commute bad that night.”

He said that although he didn’t think “breaking windows and setting things on fire” was the right way to get justice, but “at the same time [the city] using that as a reason to completely dismiss anger—that’s wrong, too. The fact that this happened means that something is wrong. … People were reacting to the same damn thing that keeps happening over and over. All the city seems to know to do about it is short-term damage control and wait until the whole thing goes away.” He imagines the thinking at City Hall to be “‘How can we make everyone feel safe until it goes away.’ I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that what they mean is ‘how can we make white people feel safe.’”

As Gerardi struggled to get to work, Cal Montgomery, who lives in Hyde Park on the South Side, was preparing to be discharged from Northwestern Memorial Hospital just off the Magnificent Mile. He heard that hospital staff was having trouble getting to and from work, and social workers, who are supposed to work with patients in person on discharge plans, were suddenly only available by phone. “That’s an access problem. Because a lot of [disabled people] have trouble on the phone,” Montgomery told The Appeal. “They were actually talking about holding my discharge because of concerns about whether I’d be able to get home.” Ultimately, he was released but had to cross a line of police at a still-operating river bridge to take the train that goes to his neighborhood. Their menacing looks surprised him. “It was clear they were waiting around for some kind of problem.”

When The Appeal contacted Lightfoot’s office for comment, a spokesperson said in an email that the mayor had “addressed this multiple times in the past” and referred The Appeal to statements she made about the shutdowns in prior press conferences. During an Oct. 30 press conference, Lightfoot was asked whether she would commit to not shutting down public transit in case of unrest after the election. As she has in the past, Lightfoot defended the practice by citing a need to protect transit workers who “felt threatened.” She said that during the unrest in May and June “we had people trying to take over buses … we had people trying to take over trains.” She said the transit employees’ union asked the city to protect their workers. (The union confirmed that Lightfoot’s statement was true.) “We know that in this city there are workers who really depend upon the transit authority to get to and from their place of business, but we also have to balance that against any security risk,” Lightfoot said. “If it’s necessary [to shut down transit] I’m not going to hesitate.”

In August, the ACLU of Illinois, which is a party in the litigation that led to federal oversight of the Chicago Police Department, filed a letter with federal court in Chicago arguing that the city’s imposition of a curfew, interruption of transit, and blockading of downtown areas “chilled speech” and had a disparate racial impact.

The restrictions “had a devastating impact on Chicagoans’ freedom of movement,” the letter stated. “People faced unnecessary hurdles, including increased police contacts, in traveling to and from protests, jobs, health care, and their homes during night hours. These hurdles had a disparate impact on the basis of race because of the outsized representation of people of color among essential workers.”

In addition to the prolonged bridge raises, road closures, and transit disruptions in response to large protests and civil unrest between May and August, the Active Transportation Alliance, a group that advocates for mass transit and improvements to walking and biking infrastructure in Chicago, has documented smaller disruptions in conjunction with more local demonstrations. In July, the Chicago Transit Authority shut down “el” stops and sanitation vehicles were rolled out to block streets as GoodKids MadCity, a youth-led community organization advocating for racial justice, staged a small party protest in front of the police department’s South Side headquarters. On Aug. 22, the CTA shut down “el” stations on the Near West Side as students organized a protest against police at the city’s elite Whitney Young High School. In September, trains weren’t stopping in the vicinity of a demonstration in the city’s South Side in honor of Breonna Taylor.

In June, Active Transportation Alliance also launched a survey to solicit Chicagoans’ feedback about the effect of the transit disruptions on their lives. They received more than 60 responses: healthcare workers said they were unable to reach patients, caretakers struggled to connect with elderly relatives, and people were unable to take care of essential needs such as grocery shopping. The group also routed more than 700 complaints about transit and bike-share disruptions to city officials.

It’s unclear whether legal action can be brought against the city for its use of infrastructure to control protests, but Active Transportation Alliance is exploring its options. “I put in a call as a resident of Chicago to the Federal Transit Administration Office of Civil Rights to see if there were grounds on which to file a complaint,” the group’s advocacy manager, Julia Gerasimenko, wrote in an email to The Appeal. “I heard back that under the umbrella of an ‘emergency’ the agencies and government officials can pretty much do whatever they please if they can justify the emergency status. They felt that a complaint process with the Office for People with Disabilities would be a process more likely [to result] in a favorable outcome.”