Washington State’s Most Populous County Curbed Covid-19 Among The Homeless By Moving Them To Hotels. But One Local Government Fought Back.

Seattle suburb Renton is battling an emergency homeless shelter through its zoning code.

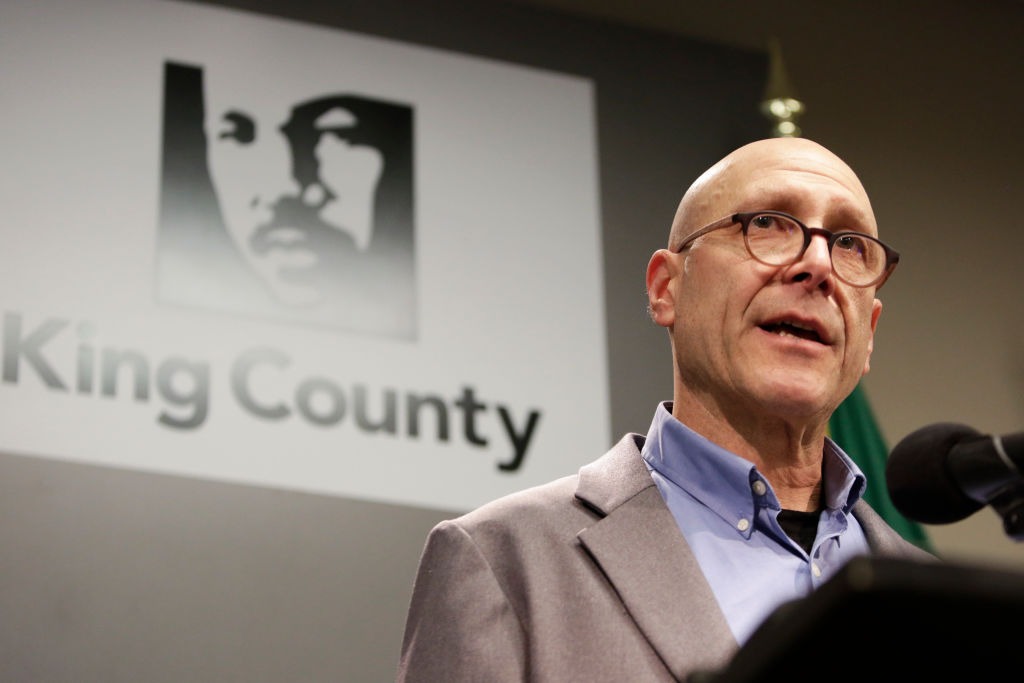

In late March, four weeks after the first COVID-19 death in the U.S. was confirmed in Washington State, King County health officer Jeff Duchin issued an emergency order authorizing all cities and towns to “reduce the density of existing homeless shelters and encampments” and provide supportive housing to higher-risk individuals in need.

By early April, officials in King County—which includes Seattle and is one of the most populous counties in the U.S—negotiated emergency leases with local hotel owners, many of whom were struggling with drastic, COVID-19 induced vacancies.

State and local officials nationwide issued “de-intensification” measures similar to King County’s in order to move homeless people out of so-called congregate shelters and into settings where they could more easily socially distance. The moves often faced local protests and legal battles.

Last year, more than 10,000 homeless adults in New York City were moved from shelters to hotels. While the most vocal resistance came from residents on the Upper West Side, early last month an appellate court ruled that more than 200 homeless men living at an Upper West Side hotel could stay at least another five months. In Austin, Texas, lawmakers just voted to purchase two hotels for homeless people, and will use diverted police budget funds to provide wraparound services for those who’ll live there. In Los Angeles, some people experiencing homelessness can be placed in hotel and motel rooms through “Project Roomkey,” and on the federal level, President Biden has ordered that FEMA increase its reimbursement rate for non-congregate homeless shelters to 100 percent through September.

But a months-long battle in Renton, a midsize suburb of Seattle, illustrates the resistance that advocates for homeless people face when relocating them to hotels, even in liberal communities.

Red Lion Hotel in Renton was one of the facilities that signed a 90-day lease with King County in April, under terms that could be renewed with 30-day extensions. The arrangement allowed for roughly 235 unhoused people living in Seattle’s Downtown Emergency Service Center (DESC) to be transferred to the Red Lion, along with DESC staff.

“Things happened very quickly, we literally had just a few days, but for many of our clients it was their first time in years with their own room and bathroom,” DESC executive director Daniel Malone told The Appeal.

The city of Renton, however, was unhappy that so many homeless people moved into the Red Lion. Officials were also dismayed with what they considered insufficient consultation from King County prior to negotiating the lease.

Renton officials demanded that King County and the DESC put in writing exactly when homeless residents would transition out of Red Lion. Local business owners complained of investing in additional security measures and dealing with property damage caused by homeless people; the police and fire departments reported a spike in 911 calls from the hotel, though they were not always tied to actual incidents requiring first responder assistance. Renton Chamber of Commerce CEO Diane Dobson, who did not respond to a request from The Appeal for comment, led the charge in lobbying the city for clarity on when homeless residents would leave the Red Lion.

In May, Mayor Armondo Pavone urged the county to close the Red Lion emergency shelter by July 9. By June, Renton issued a formal code violation against the hotel, arguing it had violated the city’s zoning laws. Among other arguments, Renton officials said the unhoused residents were exceeding the “transient” nature of hotel stays, and that the meal, medical, and mental health services provided to them exceeded the “sleeping purposes” of hotels. Renton then gave King County until Aug. 9 to relocate the residents, and pledged fines of $250 per violation per day after the deadline.

“King County must respect City of Renton zoning codes and … Renton will take action to enforce our laws—just like we would do with any other land use violator,” the mayor said in a June 30 press release. Pavone urged King County to “define a timetable and transition plan” so residents could get the long-term services they need, save county taxpayers money, “and so that “Renton citizens and businesses can be relieved of extraordinary impacts the shelter has brought to the city.”

King County officials countered in court that sheltering homeless people at the Red Lion remains necessary in light of the public health emergency and given that the county lacks “access to an equally safe or better alternative location” for the homeless residents.

Not all Renton residents supported their city’s opposition to housing homeless residents at the Red Lion. “They kept saying ‘We’re not NIMBY’ but it’s talking one way and doing something else,” local activist Winter Cashman-Crane told The Appeal.

As the dispute between Renton and King County raged, Red Lion’s owners and staff said they were subjected to abuse from the community. “Ever since we agreed to partner with King County, my partners, my employees, and I have been subject to discrimination, harassment, and vitriol by our neighbors and local community leaders,” Dayabir Bath, a co-owner of Red Lion and leader in the local Sikh community, said in a court filing last summer.

By August, the hearing examiner hired to adjudicate Renton’s complaint concluded that the emergency shelter was in violation of Renton’s land-use laws, but if King County applied for an “unclassified use” license to operate during the pandemic, it had a good chance at approval given the legal deference that public health officials receive during emergencies.

King County appealed the decision, but in November, Renton’s City Council introduced an “emergency ordinance” to define how homeless shelters can operate in their city. Renton’s proposed ordinance would limit homeless shelters to 100 people, even if there was additional space in the facility. If it passed and went into effect, over 100 homeless people would be forced to leave Red Lion by June 1, and the remainder by January of next year.

Many urged the council to reject the proposal, including Duchin, the county’s chief health officer. Research conducted by the University of Washington found that the shift from shelters to hotels was successful in stemming COVID-19 among the homeless population. The researchers also found that moving individuals to non-congregate settings improved their feelings of stability, health, and well-being, and increased rates of transition to permanent housing. “If passed, the ordinance will interfere with our efforts to control the spread of COVID-19,” Duchin wrote in a letter.

During a City Council meeting, Alison Eisinger, director of the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, said there were at least 400 fewer shelter spaces in King County than prior to the pandemic, and eliminating hotel rooms would be detrimental. “When you talk about having to pass this ordinance on an emergency basis, I wonder what that emergency looks like compared to the emergency of COVID-19, the emergency of homelessness, and the emergency of racism in our communities,” she said.

Providers noted that even if Renton characterized its new land-use category in positive terms of allowing for homeless services, in reality the ordinance carried so many new requirements that it would effectively make it impossible for organizations like the Downtown Emergency Service Center to afford operating in the city. And the 100-person cap would mean even if providers could purchase vacant hotels, they would be forced to leave rooms empty.

On Dec. 14, the ordinance passed 5-2. Chip Vincent, Renton’s administrator of community and economic development who helped write the legislation, stressed that the city wanted “to figure out how to make this work” but also “wanted to have a blueprint” for the future. He told The Appeal it bothers him that Renton “has been villainized,” and he complained that local reporters fail to mention that of the 39 cities in King County, Renton is the only one with a homeless day center in its city hall.

“I take great pride in that fact, and we have our own housing authority because we fundamentally believe it’s important to provide affordable housing,” he said. “We’re a majority-minority city, we don’t have half the assets and resources as some other cities, yet Renton does not run from these issues, and we embrace these challenges. I hate the fact that this has been communicated as Renton is a bunch of NIMBYs.” Vincent argued that the 100-person cap was necessary to most effectively serve the neediest residents.

“Council members keep saying no one is kicking anyone out, yet it’s like you’re literally putting into law something to shut us down,” said Malone, the DESC executive director. “This last year has been horrible for everybody, and it’s just been incredible that on top of the very challenging work we do in general, we’ve had to also deal with this legal and municipal code wrangling.”

Renton maintains its earlier code violation charge against Red Lion is now moot because of the new ordinance. But the lawsuit hasn’t been dismissed; Renton City Attorney Shane Moloney told The Appeal he cannot comment on it or the ordinance.

The DESC and King County plan to continue appealing the hearing examiner’s decision in Superior Court. “And we think their ordinance conflicts with the eviction moratorium and measures the county health office deemed necessary for the pandemic, and we also think it opens up new issues of discrimination,” Malone said.

In mid-December, Red Lion had its first COVID-19 outbreak even though it regularly tests its staff and residents. About 30 residents and staff members tested positive, and one resident died in early January. Malone said the outbreak can likely be traced to two fire alarm incidents at the hotel where residents gathered in the lobby and then outside for several hours.

Malone says although the DESC is searching for facilities beyond Renton, he’d like to avoid returning to its former congregate shelter in Seattle, after seeing the benefits clients experienced when they had their own rooms.

Austin’s moves on homelessness might be instructive. While dozens of residents protested the hotel purchase on Jan. 31—holding up signs that read “No Homeless In Residential Areas” and “Do You Want a 56% Increase In Crime?”—the City Council remained resolved in moving forward, and even purchased a second facility. Austin City Councilmember Greg Casar summed it up after the Feb. 4 vote: “Housing saves lives.”