Cannabis Alarmism Hinders Smart Regulations

Alex Berenson says he’s concerned there’s not enough research into cannabis risks, but his misleading arguments set scientists back.

Recent stories in major media outlets are raising the alarm that cannabis is “scary,” “dangerous,” and, amid a wave of states moving toward legalizing recreational use, “unstoppable.”

These dire warnings are coming from a new book titled “Tell Your Children: The Truth About Marijuana, Mental Illness, and Violence” by Alex Berenson, a novelist and former journalist. Mr. Berenson’s central argument is that increased cannabis use is leading to higher rates of psychotic disorders and violence in the U.S. These claims are unfortunately misleading.

Cannabis, like all drugs, can cause harm. As states move toward legalizing recreational cannabis, there’s an argument to be made that we could be doing more to minimize the harms through regulations and public health interventions. But alarmist claims undermine efforts to improve regulation.

In one of his commentaries, Mr. Berenson cherry-picks quotes from a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report to argue that cannabis causes psychotic disorders like schizophrenia. He cites this passage, “Cannabis use is likely to increase the risk of schizophrenia and other psychoses; the higher the use, the greater the risk.” But this sentence comes from a “highlights” portion of the report that does not reflect its final conclusion. While the report states there’s an association between cannabis and schizophrenia, it notes the “relationship between cannabis use and cannabis use disorder, and psychoses may be multidirectional and complex.”

There is, in fact, no basis for claiming that cannabis use has led to increased serious mental illness in the U.S.

A member of the report committee has publicly refuted Mr. Berenson’s claim that the report found a causal relationship between cannabis and schizophrenia. Put simply, correlation is not causation. Genetic risk factors may contribute to or mediate the association between cannabis use and schizophrenia. At the same time, cannabidiol, also known as CBD, may improve schizophrenia symptoms.

In the same article, Mr. Berenson points to increased prevalence of serious mental illness among 18-to-25-year-olds in recent years as proof that cannabis is fueling the rise of mental illness. But these increases appear to be driven by depressive episodes, not schizophrenia. The NASEM report only found moderate evidence associating cannabis use with a small increase in risk for depression. The report also found moderate evidence that major depressive disorder is a risk factor for cannabis use disorder, complicating any simple claims that increases in depressive episodes at the population level are driven by cannabis use.

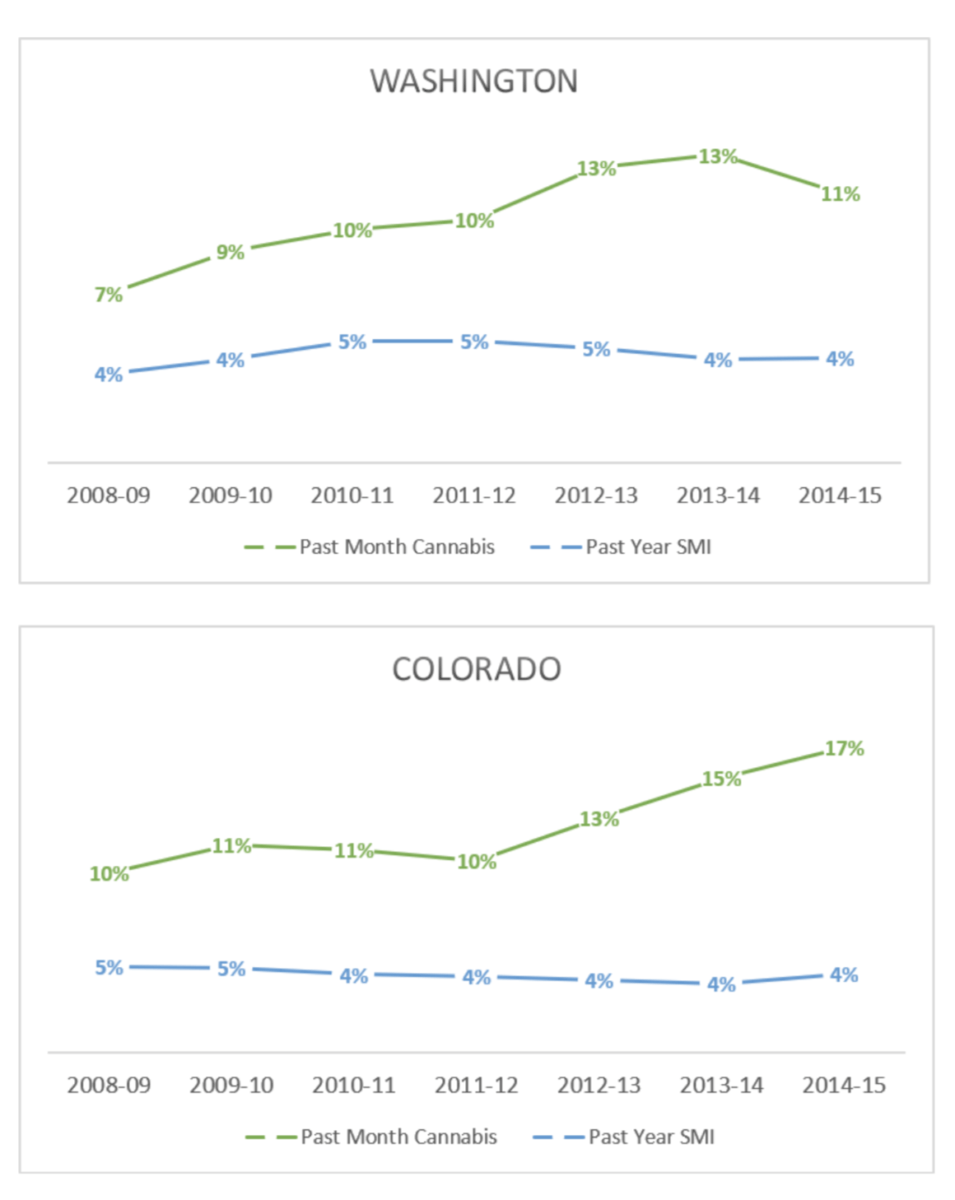

There is, in fact, no basis for claiming that cannabis use has led to increased serious mental illness in the U.S. Washington and Colorado legalized recreational cannabis in 2012. The graphs below show that while cannabis use has increased in those states, rates of serious mental illness have not.

Berenson writes that cannabis increases violence since cannabis causes psychosis and, according to him, psychosis leads to violence. Besides relying on the false premise that cannabis causes psychotic disorders, this assertion sadly perpetuates mental health stigma by painting people with mental illness as dangerous. In truth, people with mental illness account for only about 4 percent of violent acts and are more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators.

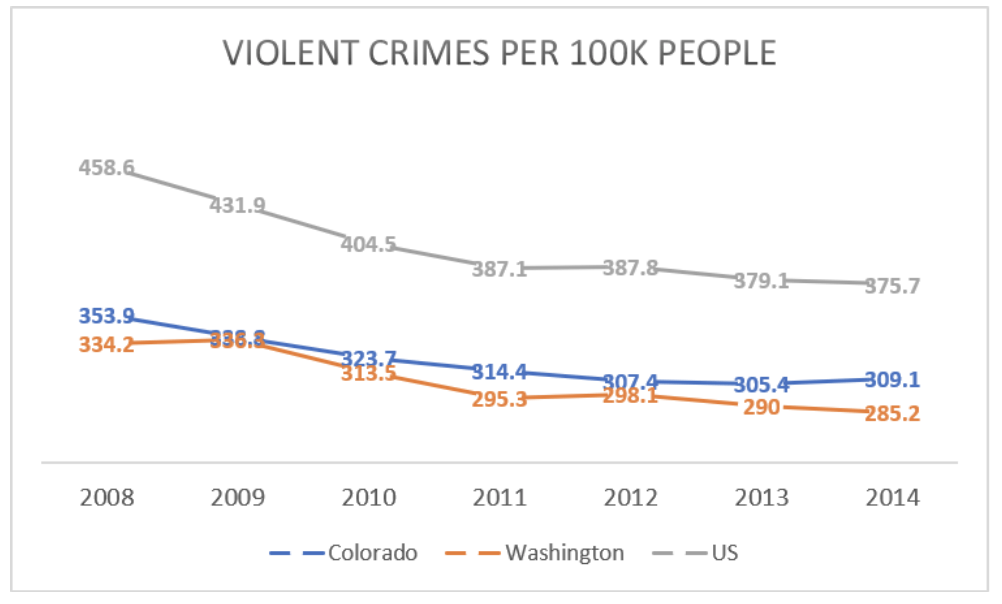

Berenson supports his argument that recreational cannabis legalization leads to higher crime by cherry-picking data from specific time-points. However, as the graph below shows, even as cannabis use increased in Washington and Colorado between 2008 and 2014, violent crime rates fell along with national trends.

Looking at a few trend lines on their own can be deceptive, since we don’t know what would have happened in these states in the absence of legalization. Fortunately, several studies have carefully analyzed the effects of cannabis liberalization and sale over time. All of these studies have found no effect on crimes or reductions in crimes from cannabis sale or liberalization. An economist found murder rates in Washington and Colorado were in fact lower than expected after legalization.

Despite what Berenson says, arguments for cannabis legalization are not based on the claim that cannabis is harmless, but on the fact that cannabis criminalization has augmented the harms of cannabis. Even in New York City, which decriminalized cannabis 40 years ago, cannabis arrest rates were the highest in the country up until a few years ago. Though rates have fallen in recent years, the burden of arrest remains highest for people of color, with Black people arrested at eight times the rate of white people for low-level cannabis crimes, even though national data show that white people use cannabis at higher rates. This approach has not reduced cannabis use but has exacted enormous monetary and social costs.

Berenson’s misleading arguments distract from his reasonable point that cannabis regulation can and should be improved. As he points out, the levels of THC, the main psychoactive part of cannabis, in legally sold cannabis today are high by historical standards. We should, as he notes, be skeptical about the role of commercial cannabis entities in policymaking, like we are for alcohol, tobacco, and pharmaceutical products. These challenges stem from our political system’s vulnerability to corruption by for-profit entities.

Berenson says he’s particularly concerned with the lack of research on cannabis harms, the high potency of cannabis products, and the growing number of people who use cannabis daily. But legalization, through rescheduling, offers possible solutions to these problems: to allow for more research into its harms, regulating the potency of cannabis products, and easing access to treatment for cannabis addiction by removing the fear of legal repercussions.

Currently cannabis is a Schedule 1 substance, under federal statute and regulations, which means that it has “…no currently accepted medical use in the United States, a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision, and a high potential for abuse.” Other Schedule 1 substances include heroin, LSD, and peyote.

The contemporary U.S. federal drug scheduling system, established in 1970, does not reflect 21st-century science and understanding of drug risk and harms to human health. Researchers from the United Kingdom created a weighted score of the harms of commonly used drugs, and their research suggests that out of 20 drugs, cannabis was eighth most harmful, behind alcohol, heroin, crack cocaine, methamphetamine, cocaine, tobacco, and amphetamines. Alcohol, the drug with the highest weighted harm score, is not only legal in the U.S., but is exempt from the federal drug scheduling list.

The Schedule 1 designation means research with cannabis is limited by strict criteria and multiple layers of review. Cannabis research is further restricted by the quality and quantity of government-grown cannabis. Congressional action is probably needed to reschedule cannabis, but Berenson’s extreme claims may scare politicians away from acting on this issue.

Ultimately, Berenson’s arguments move us backward. His misguided statements provide fodder for those seeking to perpetuate harmful criminalizing policies, while giving cannabis companies an opportunity to claim that the harms from cannabis are overblown. Both take us further from smart regulation.

Alex Gertner is an M.D.-Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. Find him on Twitter: @setmoreoff

Kelsey Priest, MPH, is a fifth-year M.D.-Ph.D. candidate at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) School of Medicine and the OHSU-Portland State University School of Public Health. Find her on Twitter: @kelseycpriest