As California Shuts its Youth Prisons, Unlikely Critics Emerge

The third installment in The Imprint’s series on the fight to close California’s youth prisons.

This article is being co-published with The Imprint, a national nonprofit news outlet covering child welfare and youth justice.

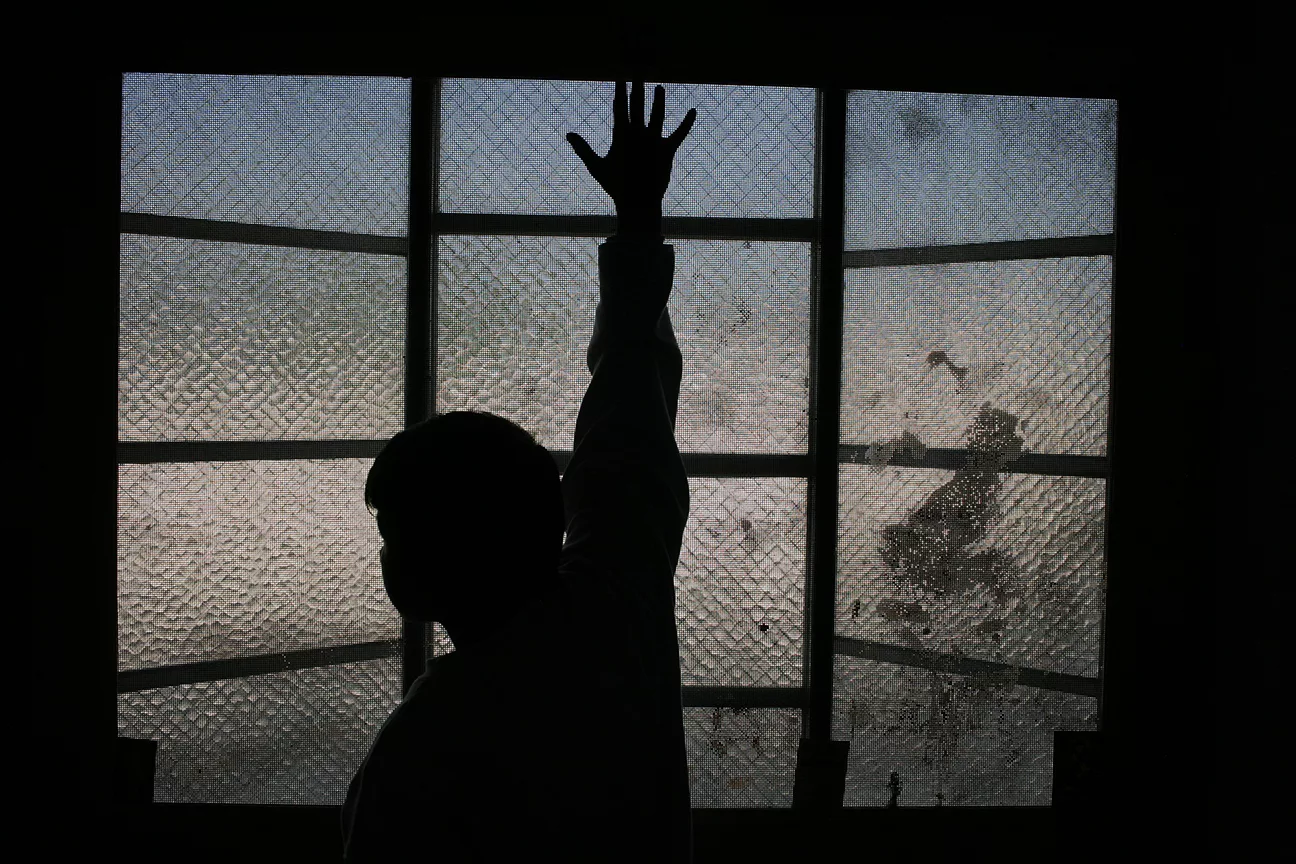

For nearly 15 years, attorneys at the Bay Area-based Prison Law Office battled officials running California’s youth prison system over inhumane conditions: “blender meals” made from ingredients like a bologna sandwich, an apple, and a carton of milk that young people were forced to drink; 23-hour cell confinement; and telephone booth-sized cages used for school and recreation.

Now—just 17 days from a legislative deadline that closes these once-teeming lockups for good—these lawyers could well be celebrating. Instead, the mood inside the Berkeley public interest firm is surprisingly grim. They fear the new plan to house young people who’ve committed crimes in local juvenile justice facilities will not be an improvement.

“The buildings may shut down, but the kids don’t go away,” said Prison Law Office Executive Director Donald Specter. “Now they’re going to be sent to places which are worse.”

Legislation that mandates the phased closure of California’s Division of Juvenile Justice requires each county to create a “Secure Youth Treatment Facility.” On paper, they are meant to be forward-looking institutions that are “evidence-based, promising, trauma-informed, and culturally responsive.” With just weeks to go before all youth—no matter the length of their sentences—must be housed and overseen by local probation departments, the reality on the ground is far different than the vision.

An Imprint review of plans submitted to the state by its 58 counties revealed that nearly all are sending young people returning from state youth prisons straight to juvenile halls. These facilities are ill-equipped for long-term stays and, in many parts of California, mired in their own dysfunction.

In Los Angeles County, the largest local justice system, violence-plagued juvenile halls are in such dire condition that state regulators have ordered they be shut down by late July. With as few as 11 percent of probation officers showing up for work, according to the editorial board of the The Los Angeles Times, life in the Sylmar and Central juvenile halls has been deemed “unsuitable” by the state’s oversight agency. Teachers can’t hold high school classes and youth are forced to urinate in their cells because there isn’t enough staff to let them out for bathroom runs.

On May 9, a teenager at the Barry J. Nidorf detention facility in Sylmar died after an apparent opioid overdose. On May 23, the California Board of State and Community Corrections ordered that and a second Los Angeles juvenile hall closed within 60 days.

Hazards on the horizon

With a mission to improve conditions inside locked facilities, the Prison Law Office set out to reform California’s youth prisons—not shut them down entirely. But even those who have long supported closure of the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) facilities say they worry about the immediate future.

Over the years, Daniel Macallair, executive director of the San Francisco-based Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, has been a vocal advocate for closing down the state youth prison system. But with that goal on the brink of being realized, he too sees hazards ahead.

Instead of reformers focusing their energy on improving a single, state-run system “now, unfortunately, we are looking at 58 county probation systems,” Macallair said, “most of which are terrible.”

County leaders are concerned as well, with many saying local governments were not given the time or resources to properly prepare to house young people found to have committed more serious or violent offenses and who will spend longer stretches behind bars.

Laura Dixon, a spokesperson for the Chief Probation Officers of California, told The Imprint last fall that county plans aim to best serve youth “with the highest needs and who have committed significant crimes,” and noted: “We expect to overcome the challenges before us because we cannot afford to let our youth or our communities down.”

‘It’s kids—and it’s worse.’

Specter joined the Prison Law Office as a volunteer straight out of law school, and took a staff position in 1979. He has served as the executive director since 1984.

“I thought I’d do it for a few years and then get a real job,” he said. Instead, he has spent his entire career fighting for the rights of people in prison.

Attorney Sara Norman joined him in 1997, eager to take on the notorious youth prison system previously known as the California Youth Authority. But Specter informed her that the office “didn’t do youth.” They had their hands full battling abuses and overcrowding in adult prisons across the country.

Then Sue Burrell, an attorney with the Youth Law Center, showed up with a sheaf of letters she’d received from young people describing their lives inside locked facilities across the state.

“It’s horrible in there,” Burrell told Norman and Specter. “It’s everything you see in the adult system, but it’s kids—and it’s worse.”

At Burrell’s urging, Specter and Norman visited the facilities to see conditions firsthand. From that point, there was no turning back.

“When you’re in a dungeon you get bread and water,” Norman said of conditions in the youth prisons. “That’s what this was about.”

Burrell remembers sitting down with Specter and Jerry Harper, a former director of the California Youth Authority, a few months after their first visits.

“We’re here because there are constitutional violations going on in your facilities,” she recalled Specter telling Harper. “I would like you to fix them. Otherwise I am going to sue you, and I’m going to win.”

‘A medieval horror story’

On Jan. 16, 2003, Specter made good on that promise. Joined by attorneys from Disability Rights Advocates and two private firms, the Prison Law Office filed suit on behalf of a California taxpayer whose nephew was incarcerated. Citing dozens of violations of the state’s constitution, civil laws, and penal code, the complaint alleged that the California Youth Authority was subjecting young people to excessive force, sexual assault, gang violence, staff-instigated fights and “inhumane, filthy, stultifying housing conditions.”

The resulting settlement required that a team of experts look into the youth prison system’s deficiencies across several areas—including health care, mental health services, education, disability programs, and sex offender treatment—and develop corrective plans.

Barry Krisberg, a respected criminal justice scholar, was the first one to take up the task, assessing general conditions.

At the time, most of what he knew about the system came from reading state-sponsored research papers produced in the 1970s, when the California Youth Authority was considered to be a national innovator, known for its quality education and vocational programs.

What he found when he went inside, Krisberg said, was “a medieval horror story.”

At Tamarack Lodge, a lockdown unit at the Preston School of Industry in Ione that young people called “the Rack,” Krisberg walked past heavy cell doors with just a peephole to look out of. Behind those doors, he said, he found young people chained to the walls of their cells.

“There’s almost nothing you can imagine that wasn’t going on there,” Krisberg, who is now retired, said in a lengthy interview. “Staff were beating up the kids. There was a lot of covering up of injuries. The medical care was completely deficient. A handful of kids were getting group counseling, but most were getting nothing. They were just vegetating.”

Krisberg, who wore a long white beard at the time and cultivated the look of an absent-minded professor, interviewed hundreds of the state’s youngest prisoners.

“I built my career on talking to violent and disturbed adolescents—I was good at that, not because I was hip or sharp, it was the opposite,” Krisberg said. “I was just this naive guy who had a beard and looked funny. The kids would talk to me, and I got them to trust that I would go out and tell people exactly what they’d said.”

State administrators, Krisberg later discovered, often had little idea what was actually happening inside the institutions. The Youth Authority chewed through directors at a rapid clip during the early 2000s, and he made sure to take each new appointee on a tour of the facilities so they could see for themselves what was taking place.

“They’d be skeptical,” he recalled, “but then they’d see with their own eyes.”

In December 2003, Krisberg released his first General Corrections Review, calling out shortcomings in facility safety, staff use of force, prevention of youth-on-youth violence and mental health care. California’s entire system was characterized by “stunning” levels of violence, Krisberg wrote. “An intense climate of fear permeates California’s youth corrections facilities.”

A gradual shift

In the years that followed, Krisberg and other subject matter experts submitted a barrage of quarterly reports documenting persistent failure to comply with the terms of the settlement and keep young people safe. Again and again, court-appointed special masters found the Youth Authority to be out of compliance.

But over time, as outside pressure imposed by advocates, lawmakers and the press grew, things began to shift inside California’s youth prisons: They were being watched. The expert reports, and the publicity they engendered, made it increasingly difficult for state officials to ignore conditions. Media investigations and legislative hearings spurred public outrage, with lawmakers demanding changes and imposing greater oversight.

Meanwhile, year after year, fewer young people were arrested and sent to state facilities. One key reason for this was a drop in youth crime that began around 2000 and continues to this day.

Bart Lubow, a longtime respected juvenile justice expert, said another reason was that the revelations that emerged from the Prison Law Office lawsuit “changed the hearts and minds of judges, who began to second-guess what they were doing when they sent kids off to the state.”

Counties grew reluctant to send young people to institutions that were now widely known as factories of abuse. Rather than fulfilling its legal mandate of rehabilitation, young people emerged worse off than when they entered, with recidivism rates that topped 90 percent during the early 2000s. Some local governments imposed moratoriums on sending youth to state facilities.

By 2007, a system that once held upwards of 10,000 youth was down to just 2,293.

Meanwhile, Specter and Norman continued to bring Youth Authority administrators before the court, demanding that they comply with the terms of the settlement. As the most abusive practices were banned and court-ordered services were introduced, conditions gradually started to improve.

In 2007, Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger signed Senate Bill 81, which limited Youth Authority commitments to only those who had committed the most serious and violent offenses, causing the already-declining population to drop even further. And as the numbers dropped, the cost to house fewer youth inside these massive warehouses skyrocketed, growing to as much as $300,000 per youth each year.

On Feb. 25, 2016, the lawsuit was finally dismissed, with the parties stipulating that the state youth prison system had “substantially satisfied” the obligations of the remedial plans submitted by the experts.

By that time, “we’d been able to change the entire culture of the system. It went from being incredibly cruel and punishment oriented to rehabilitative,” Specter said. “There was a foundation there of staff and administrators who believed in rehabilitation, believed in providing programming, and were doing their best to limit the use of force and solitary confinement.”

A game of musical cells

Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) signed the bill ordering the shutdown of the state Division of Juvenile Justice on Sept. 30, 2020. Today, as the June 30 closure date looms, many justice experts worry about what will come next for young Californians who have run-ins with the law.

The legislation to close the division requires counties to create “home-like” settings for young adults serving lengthy sentences. The Imprint’s review found counties relying instead on existing juvenile halls, adding things like comfortable sofas, gaming consoles, scent-infused “de-escalation rooms,” and sound baffles to obscure the clanging of metal doors. But many call the alterations window-dressing: Strings of fairy lights adorning fenced-in exercise yards, brightly colored paints obscuring cinder block walls, “cozy reading nooks” and starry night ceiling panels.

Counties have been given hundreds of millions of dollars for the shift, which critics say some counties have spent in ways that run counter to the state Legislature’s mandate to create “homelike” environments. Planned upgrades include more razor wire, surveillance cameras, body scanners, and the renovation of an abandoned Secure Housing Unit—the designation for a “SHU,” or maximum security unit typically used for discipline in the highest-level adult prisons.

Some county officials question whether a juvenile detention center can ever meet the needs of young people serving lengthy terms.

“The prison-like facilities that so many believed we required have been proven unnecessary and harmful,” members of a committee advising Alameda County on its plan wrote in a recent report. Their own juvenile hall, the committee added, falls short of meeting the needs of those leaving the state prisons, as it was “not built with long-term commitments in mind.”

Norman is among those eying the county efforts with growing wariness. “What we care about is our clients,” she said. “What has transformed so that kids will be kept out of carceral settings and provided the programming and services they need?”

The Prison Law Office has seen successful court settlements lead to unexpected outcomes before. Brown v. Plata—a 2011 prison overcrowding lawsuit Specter successfully argued before the U.S. Supreme Court— resulted in a court order requiring California to release 40,000 of its 150,000 adult state prisoners. Plata was a major victory for the Prison Law Office. In a dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia called the ruling “the most radical injunction issued by a court in our Nation’s history.”

But as California sent state prisoners back to the counties to reduce populations, many returned to jails where conditions were just as abysmal, if not worse. The Prison Law Office has since sued over jail conditions in Contra Costa, Riverside, Fresno, Santa Barbara, Sacramento, Santa Clara and San Bernardino counties.

ACLU National Prison Project Deputy Director Corene Kendrick, who worked at the Prison Law Office from 2011 to 2020, sees analogies between Plata and the looming closure of the Division of Juvenile Justice. “I don’t think you have to sue all 58 county juvenile halls,” she said, “but what I’ve heard so far about these ‘Secure Youth Treatment Facilities’ is not good.”

Kendrick said some youth say they don’t want to leave state facilities even though it would mean being closer to their families: “They don’t want to be in the juvenile halls because the conditions are so terrible.”

Attorney Frankie Guzman, senior director of the youth justice team at the National Center for Youth Law, spent time in both state and county juvenile facilities. He is not surprised by young people’s reluctance to return to the counties.

“The abuse, the scandals, I experienced that, and it was even worse than what people have described,” he said of his time at the Youth Authority. Like Specter, Guzman said he believes that 13 years of court intervention brought the state system “to a place, at least culture-wise, that was much better than what it was when I experienced it.”

By closing down the state system, Guzman said, Gov. Newsom “got rid of the head, but the tail doesn’t die. It just multiplies. For the youth, it’s going to be worse. Much worse.”

Macallair shares Guzman’s mistrust of California’s county juvenile probation systems, but still sees the closure as a step in the right direction, the beginning of a process that he expects to outlast his lifetime.

“We had to get rid of the old 19th century reform schools, and we did that,” he said. “The next real challenge is reform at the local level, because now you’ve got 58 different systems that were operating under the radar until now. This is going to be the reform effort of the 21st century.”

Will the Prison Law Office be compelled to take it on?

“I can’t tell you what we’re going to do next,” said Specter, “but I can tell you we are very concerned.”