‘The Darkest Part of the Tunnel’

Youth in solitary confinement wrote letters to save their lives. One lawyer responded.

This article is being co-published with The Imprint, a national nonprofit news outlet covering child welfare and youth justice.

On March 11, 1999, a thick envelope arrived on attorney Sue Burrell’s desk at the Youth Law Center.

“Well today is Tuesday and I was waiting till I got another piece of paper to let you know what was going on over here,” read one of more than a dozen handwritten missives inside.

Each letter was dated March 1, indicating a coordinated effort. The authors had been locked in cells for 23 hours a day at the N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility in Stockton, California. But somehow, they had coordinated a letter-writing campaign, hoping to reach the outside world.

One young person on suicide watch had “his hands battered repeatedly by a baton.” After “hours of banging and pleading” to leave his cell, another had been “forced to kneel in a puddle of urine fully nude in the middle of the hallway.”

Guards punished youth by sealing off their 8 by 4 foot cells with duct tape and blasting chemical agents inside.

“If this is not a meaning of attempt to murder by smothering a ward to death with chemical warfare, then I don’t know what it is,” one letter stated. The young person, who had been sent to California’s youth prison system for rehabilitation, described being “scared for my own life.”

The letters kept coming to Burrell’s San Francisco address from “disciplinary units” at N.A. Chaderjian and other lockups statewide. Youth described being beaten while kneeling in handcuffs, denied education and medical care and exercising in mesh cages. The cells were freezing, they wore only boxers, and showered in cold water.

“I continue to see the same stuff happen with no change but only for the worst,” one teenager wrote. “We need our rights protected and the only way is through some outside help and through the court system.”

He closed his letter with a request: “I truly hope you can help.”

It’s unclear how many letters like these went unanswered; how many cries for help simply echoed off prison walls. But a quarter-century ago, Burrell was listening and passing the messages along.

The direct accounts of life inside the California Youth Authority—once the largest system of its kind in the nation—would go on to reach the halls of the State Legislature, courtrooms and the mainstream press.

On June 30, California’s youth prison system, now known as the Department of Juvenile Justice, will shut its doors for good. Its closure will make California the fourth state—after the much smaller Connecticut, North Dakota, and Vermont—to take that step.

The letter-writing campaign inside the state’s youth prisons in the late 1990s and early 2000s is among the little-known contributions to this historic closure.

A life’s work

The letters spoke to Burrell, 75, on a personal level, she said in an interview. Burrell grew up outside of San Diego, with a mother whose bipolar disorder worsened over time. By the time Burrell was in high school, her mother was in and out of psychiatric hospitals, her parents were going through a divorce, and Burrell and her younger sister were often left to fend for themselves.

No matter how hard things got, “I always kept up the pretense that everything was fine,” she said, “like a lot of traumatized kids do.”

Having hidden her own adolescent struggles out of a combination of shame and determined self-sufficiency, Burrell understood the mix of courage and desperation it took for the letter writers to reach out to a stranger. So setting the letters aside without responding never felt like an option.

In the mid-2000s, Corene Kendrick, now deputy director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project, had the office next door to Burrell’s. She recalls the letters and all the other documents Burrell built into an “idiosyncratic” but “masterful” library system.

“She had these stacks of papers and reports and court filings covering basically every square inch of her office and the floor,” Kendrick said, “except for a path to her chair and a path to the guest chair.”

Burrell may have been the right person for the young prisoners to write to. But the fact that their letters even reached her was something of a fluke.

In 1989, the Youth Law Center sued the California Youth Authority for failing to provide special education services. A subsequent legal settlement required that formal notice be posted in the living units of the 11 youth prisons statewide. Burrell’s work address appeared at the bottom of the flier.

Like most civil rights shops, the Youth Law Center’s mandate was to advance systemic change through class action litigation, and it wasn’t Burrell’s job to respond to individual concerns. Still, she answered every one of the dozens of letters that would eventually show up.

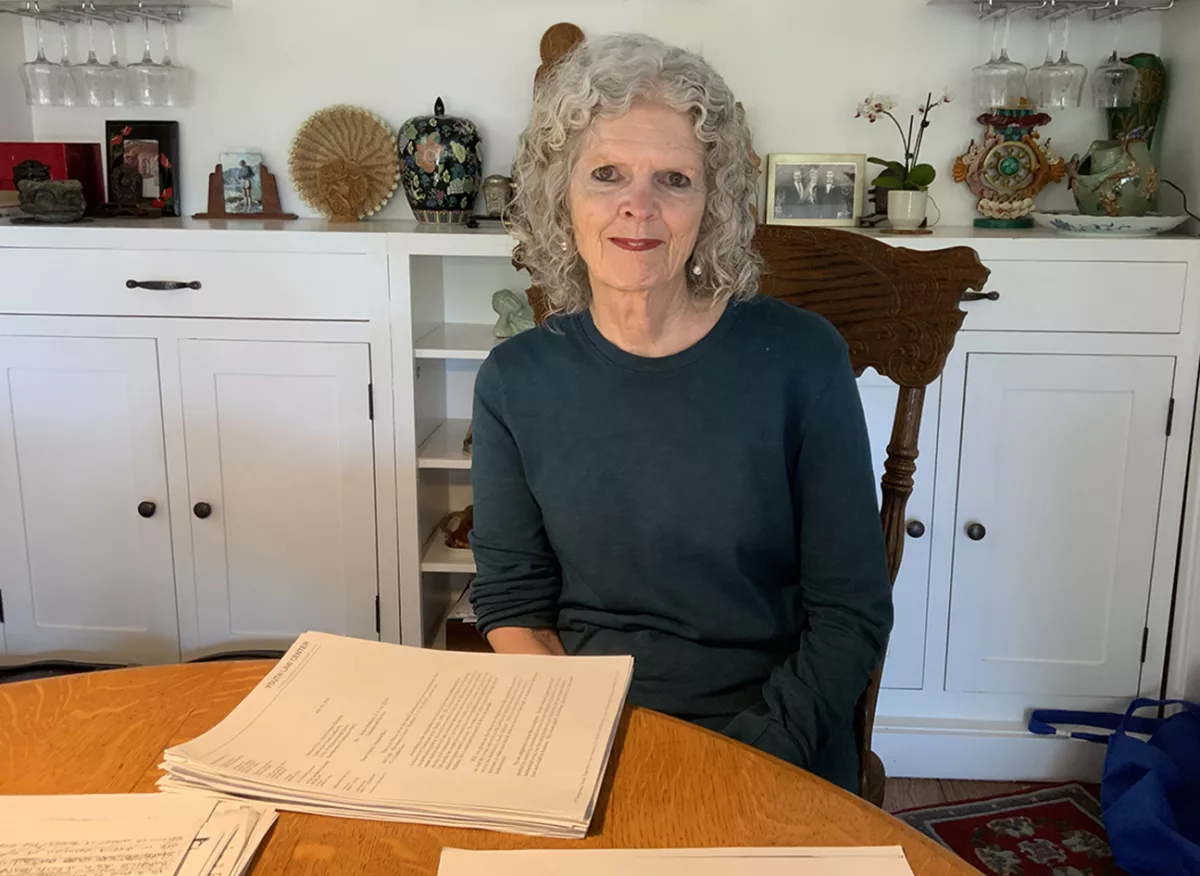

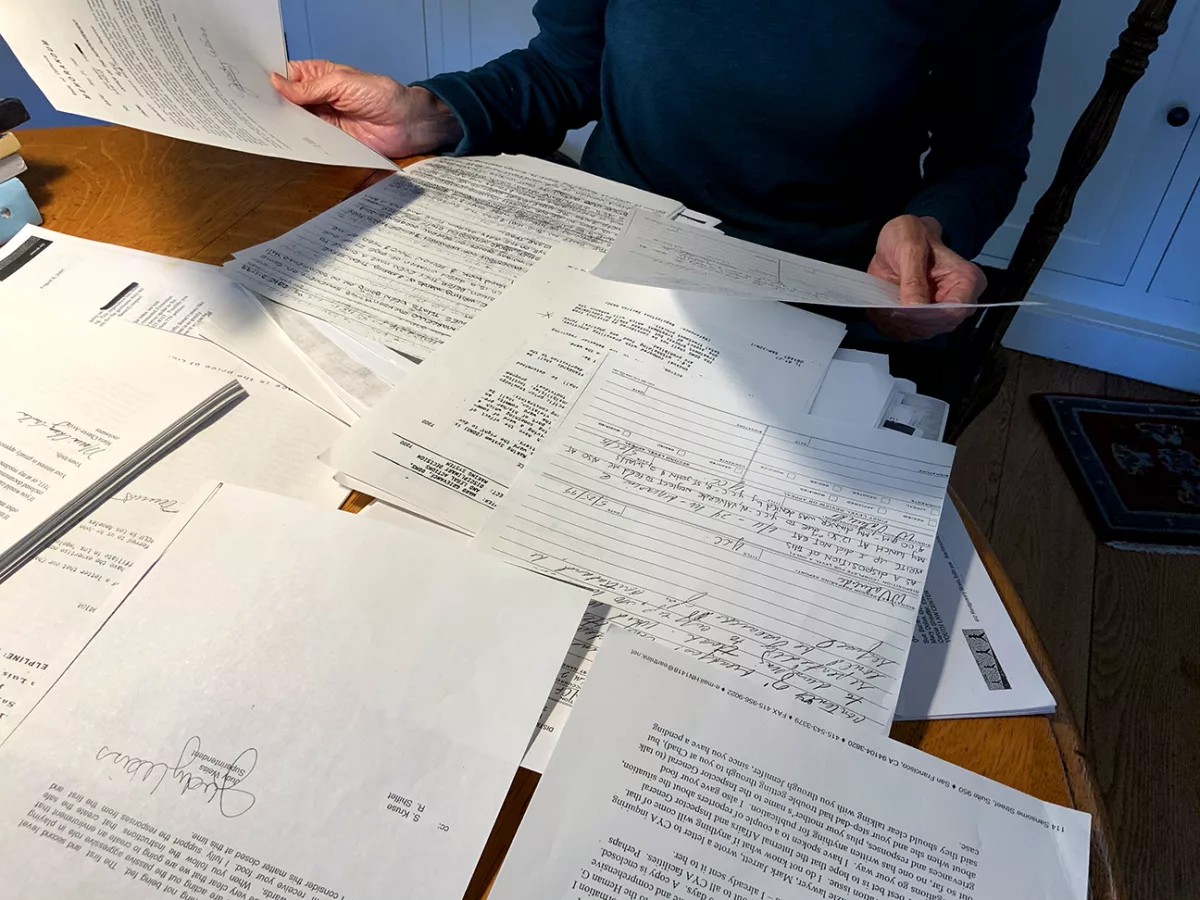

“I felt a huge responsibility, because I knew that if I didn’t do it, it was likely no one would,” Burrell said from her San Rafael home. She has recently retired from a 45-year juvenile law career, and during an interview, the letters were spread out on her kitchen table.

“They really didn’t have anywhere to turn,” she said.

Advocating from the inside

The first letter in Burrell’s extensive archive, dated Feb. 3, 1994, took a while to reach her desk, and it was not written by a young person. Initially sent to the American Civil Liberties Union’s San Luis Obispo office, the letter was later forwarded to the ACLU’s larger Los Angeles affiliate. The letter was unsigned, but appears to have been written by a staff member at the Paso Robles School for Boys in Central California. It described the way guards responded when fights broke out.

“The boys are stripped down to their boxer shorts, hands cuffed behind their backs, and they lie on the gym floor, head turned only in one direction. The pain is unbearable quickly and if they move, they are placed on their knees, nose to the brick wall, hands cuffed behind them, and left like this for hours,” the author wrote.

The letter went on to detail the practice known as “temporary detention” or “Gym TD,” using the institutional name “wards” for the incarcerated youth, ages 12 through 25.

“They have helmets, which are football helmets. They strap these helmets on the heads of those wards who are trying to beat their heads on the floor to knock themselves out,” it stated. “This is common. The wards lie on the floor and dream of revenge.”

The ACLU was not taking “these types of cases,” according to the cover letter Burrell’s office received in response. At the time, no one was.

Inside California’s overcrowded youth prisons that housed nearly 10,000 at their peak, grievances and parents’ complaints went nowhere, and public defenders dropped their advocacy once teens were locked up. With few outside observers let in, guards dispensed deprivation and used excessive force with impunity.

“I don’t know all the rules and laws, but I do know a lot of things aren’t being done correctly or by guidelines,” one young man wrote from N.A. Chaderjian in Stockton on March 1, 1999. “That’s why we’re all writing you and asking for your help.”

Burrell’s archives contain not only the letters she received from young people and their families but also her extensive follow-up. She shared the content of the letters with successive CYA directors, wardens, general counsels, Inspectors General, legislators, and reporters across the state, who followed up with investigations of their own.

The ACLU’s Kendrick said Burrell’s ability to use the correspondence to tell a personal story highlighted the harms of harsh youth imprisonment more than any abstract legal argument ever could.

“In terms of moving litigation or legislation forward, you really have to humanize the story,” she said.

The young people who wrote to Burrell often had no access to a law library or even basic education. Young people on isolation units known as “23 and 1” were not allowed to attend school; at best, they received worksheets slipped through the food slot in the door to their cells. One apologized for his handwriting—he was writing with a sliver of lead from a pencil someone had smuggled onto the unit, and it was the best he could do.

Despite these obstacles, the youth showed a sophisticated understanding of their rights and a noteworthy ability to advocate for others. Many of the letters described the circumstances of peers, and used the pronoun “we.” One teen obtained a copy of a wards’ rights handbook and numbered his concerns, identifying the section codes being violated. Another did the same with the U.S. Constitution.

On April 23, 1999, a young man at N.A. Chaderjian wrote that he had spent 10 and a half months on a lockdown unit and did not know why or how long he would remain. While there, he was denied access to school and to groups that the parole board required him to attend before he could be released.

“What I’m asking for is something out of the Title 15 or any documents that could shine some light on my situation, because as of now I am at the darkest part of the tunnel,” he wrote, referring to the state code that regulates detention facilities. “I know that something is not right, as far as legal time limits etc. goes, but I have no document stating facts.”

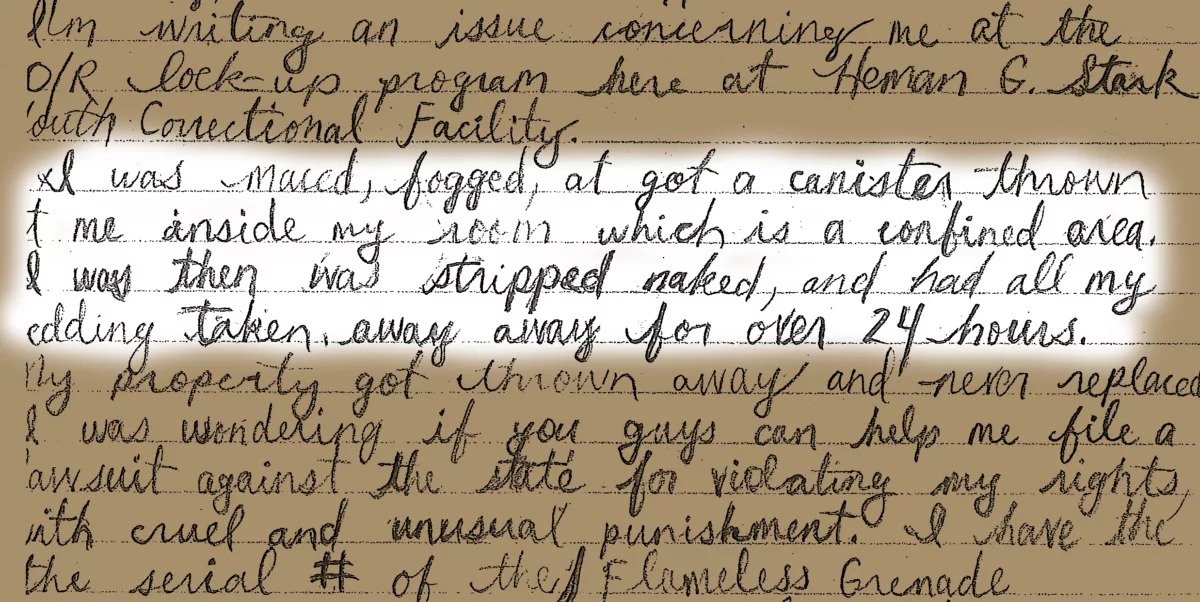

One letter-writer described having a chemical grenade thrown at him inside a poorly-ventilated cell, then being stripped naked and left to sit in the noxious fumes. Even in that state, he managed to jot down the serial number and full title on the canister—“Flameless Grenade/ Chemical Irritating Agent”—“so they can’t say I made it up.”

Further describing the label, he wrote, “It also states that: Do not use in confined areas. Do not throw directly at persons as serious injury or death may result.”

As if foreshadowing the future, he added: “I feel only a lawsuit can stop this from happening again to other wards.”

Sometimes the letters came from parents who were writing because their sons did not have access to paper. The mother of a ward at N.A. Chaderjian wrote that her son had been punished for banging on his cell door because his room had no running water and the toilet was unusable. She stated that guards had sprayed him with Mace, stripped him, taken away his mattress and bedding, and left him in a bare cell in “excruciating pain” until he fainted.

“Although I am cognizant of where my son is,” she wrote, “I still do not believe that he should be tortured.”

Institutional resistance

Burrell’s archives contain not only letters from young people and their families but also a record of her efforts on their behalf. Whenever possible, she sent direct responses to the youth. No problem was too large or too small for consideration.

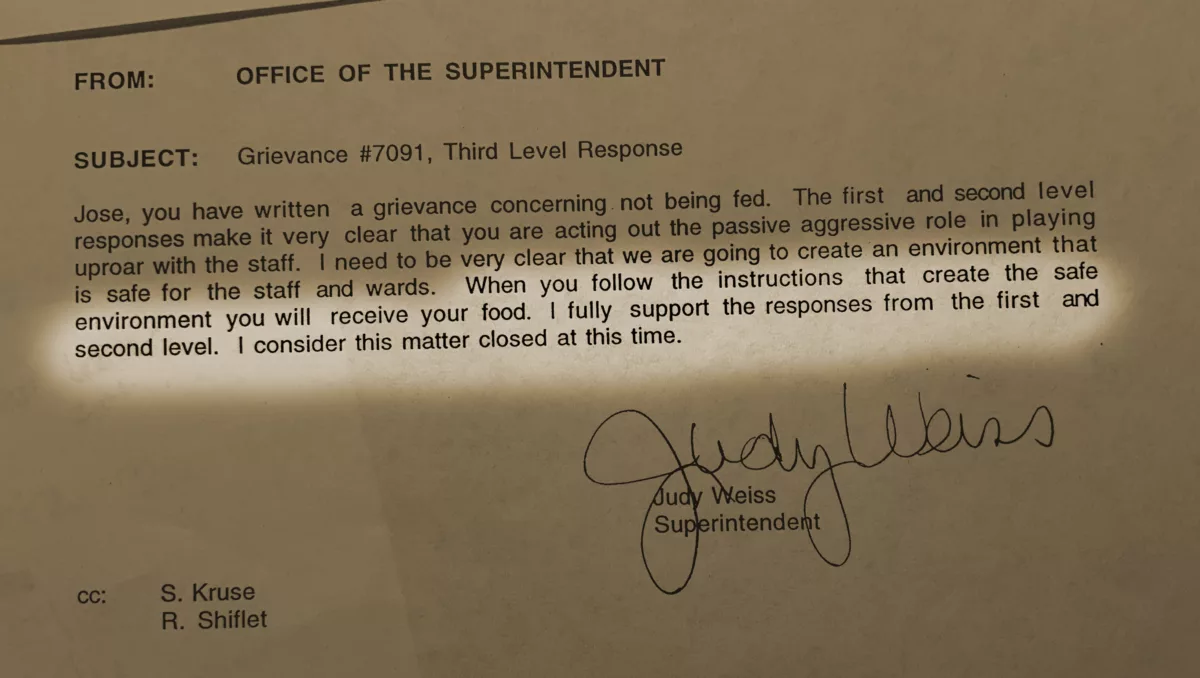

In July of 1999, a young man wrote to report that his meals had been withheld at N.A. Chaderjian as a form of punishment. His offense had been neglecting to show his empty milk carton when he emptied his tray into the trash, then refusing to extend his hands through the slot so he could be cuffed and his room searched for contraband. He enclosed copies of the grievances he filed and the responses he got from the superintendent.

The lengthy back-and-forth that followed reveals the challenges Burrell faced.

“You will not receive an investigation into the matters you have addressed,” Superintendent Judy Weiss wrote on June 28, 1999, in response to the grievance. “When you follow the instructions that create the safe environment you will receive your food.”

She signed off, stating: “I consider this matter closed at this time.”

Weiss also defended the practice of sealing cells with duct tape. In a March 22, 1999 article, she told The Stockton Record it was a “creative solution” to the problem of guards forced to breathe the chemical agents intended to subdue youth.

Burrell was not satisfied with denials or dismissals of the grievances. And the denial of food felt like one outrage too many.

“Couldn’t they just toss the kid a peanut butter sandwich?” she noted to herself on the letter from the youth who was denied food at N.A. Chaderjian.

Burrell eventually forwarded copies of the grievances and the superintendent’s response to State Senate President Pro Tempore John Burton. That move got the attention of Youth Authority Director Greg Zermeño.

“The Department’s policy is that wards are always fed,” Zermeño wrote in a three-page letter to then-Sen. Burton, dated September 29, 1999. He attached a relevant page from the Youth Authority Institutions and Camps manual, which prohibited the withholding of food as a disciplinary measure.

This young man’s experience, he wrote, was one of those “rare occasions” when a ward “may choose to miss one or two meals as a form of protest.”

As for the cages used for exercise and school on lockdown units, Zermeño wrote in a letter to Burrell that while he agreed their appearance was foreboding, “countless” young people had told him how much they liked them.

“I believe the concept is very good,” he wrote.

The beginning of the end

Over the years, there were frustrations and disappointments. But Burrell was able to win small victories for some of those who wrote to her—doctor’s appointments, family visits, access to a high school class, or transfers to other prisons. Even when she couldn’t effect change, her calm, consistent replies encouraged young people to continue advocating for themselves.

On Sept. 1, 1999, the teen who had been denied his meals followed up with thanks for “your most welcome letter” and an update on his own efforts.

“I am still studying in the law library to find supporting cases,” he wrote. He enclosed a copy of a 1966 U.S. District Court case that found that denying food and water to a prisoner in solitary confinement violated the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

Others simply pleaded. “Please please please get me out of here, I’m scared of this place,” one letter stated.

Burrell developed a multi-step process to handle the complaints.

“My first duty is to see if I can get relief for the young person,” she said. “But then, especially as I started getting these dismissive responses, I realized that I could use them to make a record.”

Often, the institutional response felt hollow. At one point before the cages were banned in 2004, the institution painted the bars turquoise and green and renamed them “Secure Program Areas,” or “SPAs” for short. Burrell recalled a prison superintendent quipping to her that her advocacy had resulted in the new moniker; he called them “Sue Burrell Secure Program Areas.”

But the record created by the letters—followed by years of legal battles and grassroots advocacy—helped spark a decades-long effort that would reform, shrink, and ultimately shut down the California Youth Authority.

In the next installment in this series, read about the Bay Area public interest law firm that sued to shut down the California Youth Authority and warnings pro bono attorneys offer for the future of incarcerated youth in the nation’s most populous state.