‘Inside of an Oven’: Climate Change is Cooking California Prisoners, Report Warns

A new survey of more than 500 people incarcerated in California state prisons warns that large numbers of people have been subjected to extreme heat, dangerous cold, flooding, and wildfires.

Incarcerated people in California are suffering from extreme heat, flooding, wildfires, and other effects of climate change, according to a new report out yesterday that surveyed more than 500 state prisoners between January and February.

Most said that if a climate emergency strikes, they believed prison staff would lock them in their cells and escape to safety. Graduate students from the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs produced the report for the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights.

“So far as I know, in the case of any natural disaster, the prison staff will close my room door and leave,” one respondent incarcerated at Pelican Bay State Prison said. “If things would be otherwise, I would like to know.”

To address the issue, the report’s authors recommend the state close facilities most vulnerable to climate disasters and reduce the prison population by half. Officials should also prioritize releasing older people, those with certain medical conditions, people with mental illness, and those with physical and developmental disabilities. To further fix climate-related problems, researchers said the state should divert money from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR)’s more than $14 billion budget to expanding re-entry services and to bolstering heating, air conditioning, ventilation, shade, and backup generators in the state’s prisons.

“I really don’t see CDCR being ready for climate emergencies,” one survey respondent stated. “It’s hard for them to answer a call for a cell fight.”

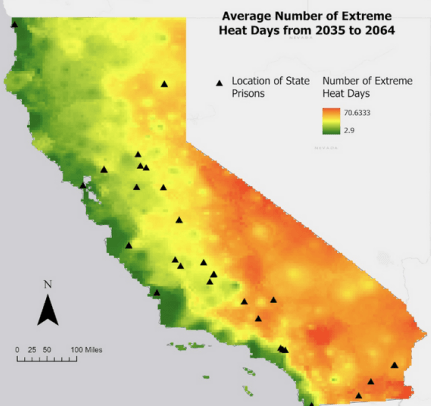

Eighteen of California’s prisons—which incarcerate approximately 46,000 people in those facilities alone—are located in areas vulnerable to extreme heat, wildfires, or flooding, according to the report.

Like many parts of the world, California has experienced record-high temperatures in recent years. Extreme heat is brutal inside the state’s overcrowded prisons, which typically lack proper ventilation and are built with materials that retain warmth. Some of the facilities sit in the desert. Others are nearing or have already surpassed 100 years of age: An incarcerated firefighter told researchers that when he arrived in 2020 at San Quentin State Prison—which opened in 1854— it felt like “we were inside of an oven, just cooking.”

Despite these dangerously rising temperatures, survey respondents reported that they’re provided little relief from the heat. Sixty percent had never had access to air conditioning on sweltering days, and more than 60 percent said their shower use had been limited due to the department’s water conservation efforts. A majority reported that staff had never allowed them access to ice on hot days. Almost 90 percent said they had used water from their cell toilet or sink to cool down.

Respondents taking medications that make them vulnerable to heat-related illnesses reported that they had experienced heat stroke, cramps, or heat exhaustion.

“There have been multiple times when the power and generator has failed during heat waves and I have suffered asthma attacks and passed out to sleep,” a survey respondent incarcerated at San Quentin told researchers. “These power outages [occur] at night when [we] are locked in our cells.”

CDCR’s plan for extreme heat, identified as temperatures exceeding 90 degrees, states that staff may take several actions to protect prisoners—such as increasing access to water stations, fans, showers, and ice—but does not require them to do so. If directed by medical staff, officers are supposed to provide prisoners with liquids with electrolytes. The policy appears to give vulnerable prisoners more protections, including moving people to air-conditioned spaces if the indoor temperature rises above 90 degrees.

In addition to extreme heat, a significant number of prisoners also said they had experienced several climate emergencies, including exposure to wildfires and smoke (about 45 percent), extreme cold (almost 40 percent), and flooding (about 14 percent). More than half of all respondents said they had no access to heated facilities during cold weather. And, of those who experienced a wildfire nearby, 82 percent said they had irritated lungs, eyes, or throats from the smoke.

Most who experienced freezing weather reported that they had developed numbness in their hands or feet. One survey respondent incarcerated at Pelican Bay State Prison said that during the winter, the cells frequently flood with sewage and excrement.

Even though climate-related crises have already impacted incarcerated people, the report says that CDCR and state officials seem unprepared to keep people safe during climate disasters. Survey respondents echoed this concern.

The overwhelming majority of surveyed prisoners said they were unaware of emergency plans in case of wildfire, extreme heat or cold, and flooding. One person reported that they had participated in only three fire drills in their twenty years of incarceration. Many fear CDCR officials will handle climate catastrophes as disastrously as the COVID-19 pandemic—when the state left people in overcrowded units, unnecessarily exposed them to the virus, and denied them programming, visits, and other rights.

“We feel hopeless and understand [that] if anything happens, we are out of luck,” said one survey respondent from Ironwood State Prison. “We witness[ed] it during the COVID-19, when [correctional officers] just lock themself in the office and keep us locked down. We’ve seen how chaos would work in here, and [it’s] not in our best interest.”