Newsletter

California Politicians are Disguising Homeless Sweeps as “Care”

Newsom’s measure—called “CARE Court”—paves the way for family members, state officials, and first responders to force more unhoused people into court-ordered treatment programs for a period of up to two years.

California Politicians are Disguising Homeless Sweeps as “Care”

by Jerry Iannelli

California is experiencing the worst affordable housing shortage in the nation—and, not coincidentally, the country’s largest and most visible homelessness crisis as well. But rather than address the root of this crisis, the landed gentry and other special interest groups who largely run state politics have demanded aggressive action to sweep aside its most conspicuous symptoms. Some conservative-leaning elected officials have responded by proposing acts of outright cruelty, like shipping the unhoused out of town entirely.

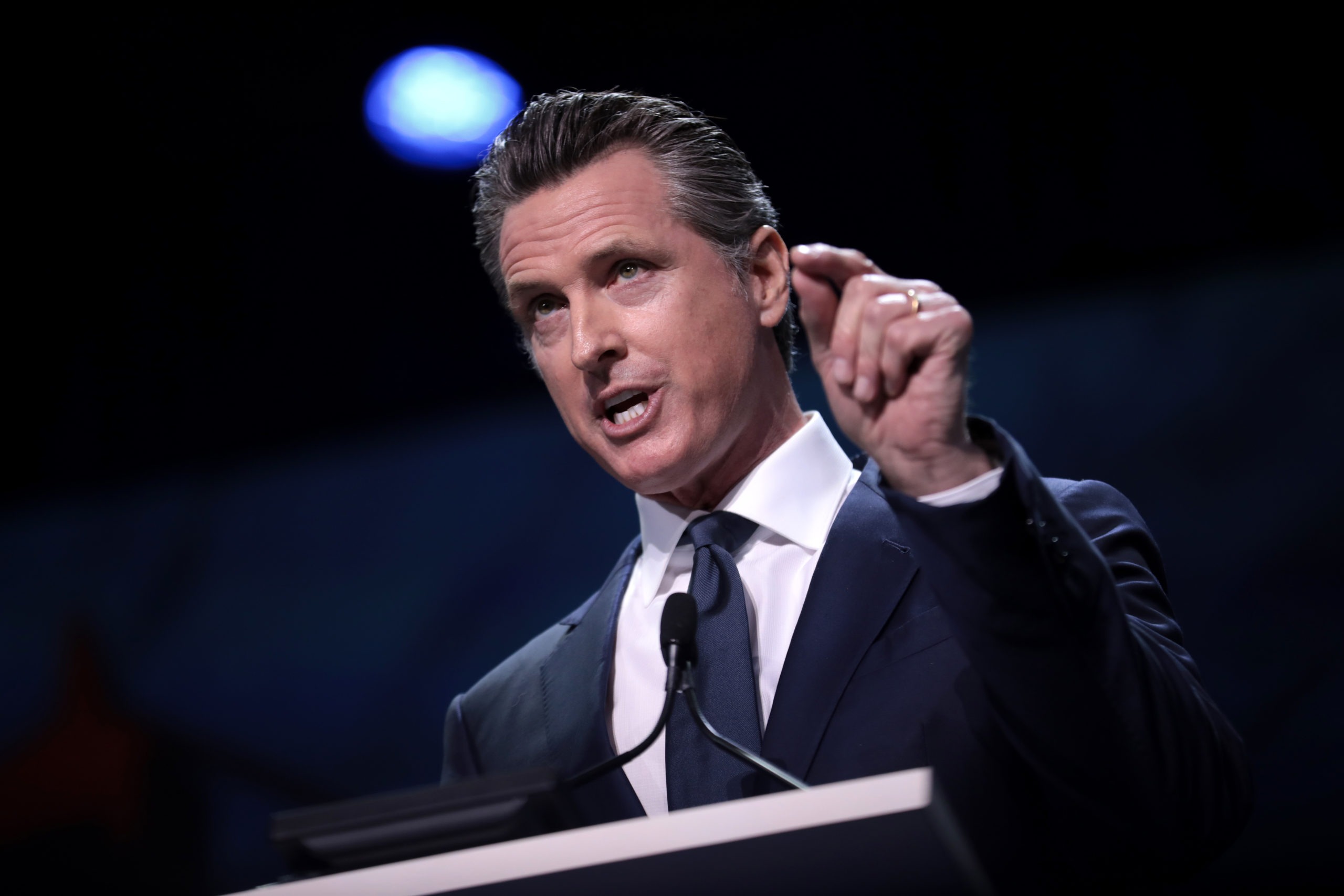

But two of the state’s most powerful Democrats—Gov. Gavin Newsom and newly elected Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass—have gone to greater lengths to disguise their homeless removal efforts as “caring” and “compassionate,” rather than favors for the local real estate and business owners who control state and local politics.

Over the past year, Newsom and Bass have each launched their own programs designed to get people off the streets—humanely, of course. Under legislation championed by Newsom and passed by the state legislature last year, local officials will soon be empowered to force certain unhoused individuals into psychiatric treatment, a plan that numerous mental health advocates and civil rights groups oppose. And, in the last month, Bass has begun pressuring unhoused Angelenos to move into city-provided motels. While the measure is intended to be temporary, it carries only a vague promise of a permanent home, tied to yet-to-be-constructed affordable housing units.

Both plans carry significant risks: Advocates for the unhoused fear that Newsom’s will further traumatize vulnerable people by using police and the courts to force them into medication regimens or therapy. Bass’s program, meanwhile, hinges on pushing developers to build thousands of as-yet-unannounced affordable housing units, a process historically mired in construction delays, angry homeowner’s groups, and red tape.

Despite these major shortcomings, Newsom and Bass have succeeded in convincing large swaths of the media and public that their proposals are acts of care for the unhoused.

Newsom’s measure—called “CARE Court”—paves the way for family members, state officials, and first responders to force more unhoused people into court-ordered treatment programs for a period of up to two years.

The proposal passed through the state legislature last year, despite pushback from mental health professionals who argue that court-ordered treatment programs are actively harmful. In June, as Newsom was pushing lawmakers to adopt his proposal, the ACLU of California’s lobbying group begged legislators to spike the idea, stating that it would “unravel decades of hard-won progress by the disability rights movement to secure self-determination, equality, and dignity for people with disabilities.”

Critics have also panned the bill for failing to guarantee housing to CARE Court participants and for doing nothing to mandate the building of new, affordable homes. While Newsom’s administration has separately funded the creation of new housing units for the needy, the CARE Act signed into law last year only states that someone funneled into CARE Court “may” be given housing resources afterward, which means people could be forced to adhere to medication regimens or other requirements while still living on the street.

The basic contours of Newsom’s plan bear a striking resemblance to an initiative New York City Mayor Eric Adams unveiled late last year. As advocates told The Appeal then, forced treatment can leave people with lifelong trauma and economic consequences. Individuals hospitalized for mental health issues can be barred from obtaining a host of professional licenses, denied access to higher education, or prohibited from getting a commercial driver’s license. In some cases, they can even lose the right to parent their own children. Studies have also found that young people involuntarily hospitalized are less likely to seek medical help if they feel suicidal and, overall, say they are far less trusting of the medical system.

Newsom has done little to address or even acknowledge these concerns. In fact, to hear it from the governor—or the news outlets that have credulously parroted his descriptions of CARE Courts—he is responsible for a kindness befitting a modern-day Mother Teresa.

“CARE Court is about meeting people where they are and acting with compassion to support the thousands of Californians living on our streets with severe mental health and substance use disorders,” Newsom stated in a press release last year.

While the state’s first CARE Court programs are set to begin operating later this year—including in Los Angeles County by Dec. 1—Mayor Bass isn’t waiting to start sweeping LA’s unhoused out of sight. In December, she announced “Inside Safe,” a program that offers to move people from the streets into city-provided motel rooms. Bass has promised the initiative will give participants a shot at obtaining permanent housing.

Worryingly, however, Bass has begun displacing people—starting with a longstanding homeless encampment in Venice—without announcing concrete plans to build affordable homes. So far, Bass has offered little more than a pledge to vastly speed up the permitting process for new construction projects.

While it’s possible Bass does make good on such an offer, the odds are not in her favor: Los Angeles real estate is prohibitively expensive and local homeowners and business groups tend to fight similar projects with the fervor of religious fanatics. The last local attempt at a “housing first” homeless policy, a federally funded program called Project Roomkey, only housed one-third of the people it had initially planned due to a lack of resources. (Helpfully, however, Bass’s administration will start receiving an influx of cash on April 1 thanks to Measure ULA, a 2022 ballot petition that levied a new tax on the ultra-wealthy in order to fund affordable-housing and rental assistance.)

Participants of Inside Safe have reportedly been pressured to throw away tents and other belongings as a condition of the program. If they eventually lose access to their new housing, they will likely be left with less than they started with. And, while Bass has claimed Inside Safe will only “voluntarily” move people into motels, the city’s outreach comes with an implicit threat. Those who remain on the street may later be forcibly moved, fined, or even arrested as part of the city’s draconian outdoor-camping ban, a law that Bass has said she supports. (Bass has also taken flak from advocates for the unhoused after the city cleared homeless encampments near Los Angeles City Hall days before her inauguration last month.)

As with the CARE Act, Inside Safe has holes that carry the serious potential to cause harm. The attempts to market these approaches as “compassionate” reek of political gamesmanship, hasty planning, and a focus on optics rather than substance. Despite being pitched as transformational acts of healing, the only thing either plan fully guarantees is that the unhoused, at least for the time being, will be moved out of public sight.

In the news

Los Angeles police killed a 31-year-old Black high school teacher who had gotten into a traffic accident and asked them for help. The victim, Keenan Anderson, was the cousin of Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors. [Sam Levin / The Guardian]

Police killed over 1,100 people in 2022, the highest number in a single year since Mapping Police Violence began collecting data ten years ago. Nearly 1 in 4 victims were Black, even though Black people make up about 13 percent of the U.S. population. [Sharon Zhang / Truthout]

Eteng Ettah takes a look at “how the carceral system showed up—and was dismantled—in the most popular shows of 2022.” [Eteng Ettah / Scalawag]

Last August, Larry Price, who had paranoid schizophrenia and a developmental disability, died in his cell at the Sebastian County Jail in Arkansas. His cause of death was dehydration and malnutrition. Earlier this month, his estate filed suit against the county and the jail’s healthcare provider. [Tesfaye Negussie / ABC News]

Appeal Board member Josie Duffy Rice’s premiered a new podcast, UNREFORMED: the Story of the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, where thousands of Black children were subjected to physical and sexual violence and forced to work in the fields surrounding the school. [Josie Duffy Rice / Twitter]

ICYMI — from The Appeal

The police killing of Tortuguita, a protester in the Atlanta forest, follows months of escalations by law enforcement against the Stop Cop City movement. Aja Arnold reports on the fallout and questions swirling around the official narrative of the shooting.

A recent policy change in New Jersey was just the latest result of a debate that often frames the humane treatment of trans prisoners as a threat to the security of the rest of the population—especially in the case of trans women, writes Adam Rhodes.

Proposed legislation in New York would amend the state constitution to end the nearly 200-year-old practice of felony disenfranchisement. The bill’s sponsors write that it would be one way to honor MLK’s legacy on voting rights.

Elizabeth Weill-Greenberg reports that kids at Angola have been locked in their cells for days at a time, only allowed to leave to shower, according to a teen who was held at the former death row unit. The power often goes out when it rains. When it’s cold, there’s no hot water. Weill-Greenberg discussed her reporting on KPFA’s Law and Disorder with Cat Brooks.

That’s all for this week. As always, feel free to leave us some feedback, and if you want to invest in the future of The Appeal, donate here.